With supermarket shelves bulging with Passover muffins, Passover granola and even Passover breadsticks, it’s hard to grasp that for much of history, this holiday’s fare was limited to the simple and home-made. In the shtetl, Passover preparations began at Chanukah when housewives rendered chicken and goosefat into schmaltz, the cooking fat of choice before people started counting calories and cholesterol.1

Another important job was making rosl, a now-almost-unknown pungent crimson-colored beet broth that was considered the height of gourmet cuisine in Eastern Europe. On Purim, the pickling process began as shtetl Jews kashered barrels and then filled them with cut-up beets which would ferment and eventually find their way into holiday soups (rosl borscht), horseradish, meat dishes and even a beet-based jam called eingemachts.2

Wines were homemade too, fashioned from fermented raisins—the brownish-yellowish drink preferred because it looked less similar to blood than grape wine and would hopefully deflect blood libel accusations, which were rife during the springtime. Levantine Jews also fermented grapes, brewing a potent liquor called raki which they enjoyed on Passover. In The Book of Jewish Food,3 author Claudia Roden points out that in Morocco and North Africa, where Muslims don’t drink wine or spirits, Jews distilled grapes and raisins to make wine for sacramental and other purposes.

In the Middle East, Passover preparations included the manufacture of silan, a sweet date honey that was used in charoset and as a jam.4 For kitniyot-eating Sephardim, rice checking was another critical job, with the holiday rice spread on a white cloth and inspected three times to ensure that it wasn’t mixed with wheat kernels.5

The roots of our modern store-bought Passover matzah date back to 1838 when an Alsatian Jew named Isaac Singer invented the first machine that rolled the matzah dough, popularizing “machine-baked matzah.” While his invention caught on in Central and Western Europe, many Eastern European rabbis denounced machine-made matzah, some saying it was no better than chametz. In the States, where Jewish observance was somewhat more lenient, machine matzah became the matzah of choice. In the 1880s, a Lithuanian immigrant named Dov Behr Manischewitz opened the first matzah factory in Cincinnati, Ohio, where matzahs were baked “under the most sanitary conditions guaranteed to be strictly kosher,” at least according to the label.6

With the newspapers full of stories about contagious diseases, late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century Americans, including Jewish immigrants, were highly germ phobic. Most American Jews at the time preferred Manischewitz’s “hygienic” factory-made matzahs to the old-fashioned, irregularly shaped matzahs baked in cold cellars.

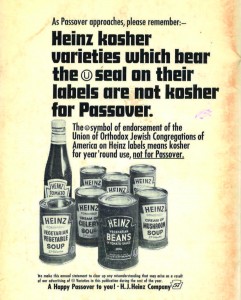

Heinz ad on the back cover of Jewish Life, spring 1965. Jewish Life was the predecessor to Jewish Action.

Manischewitz also pulverized matzah into a meal that was soft enough to bake; the new product was revolutionary. Shtetl matzah meal made with a hammer-like implement couldn’t be baked into fluffy cakes. “Manischewitz did for matzah what Henry Ford did for cars,” explains OU Rav Hamachshir at Manischewitz Rabbi Yaakov Horowitz. Suddenly, matzah was being produced on a mass scale. Nowadays, says Rabbi Horowitz, were it not for machine-matzah, many Jews would not have access to this Passover staple.

From the 1920s onward, the company also sponsored a very popular Yiddish-English cookbook called Batamte Yidishe Maykholim (Tempting Kosher Dishes) to combat “matzah monotony” and teach housewives how to use its products. Along with the traditional matzah kneidlach and matzah brei, the cookbook featured recipes for Passover Boston cream pie and Passover Napoleons. Still, the focus was on the home cook. It wasn’t until after World War II that Passover food became mass produced and factory made.

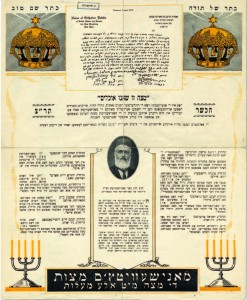

Certificate testifying that Manischewitz matzahs are kosher for Passover, New York City, 1930. From the Archives/Library of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

Among the first of the new products was the Passover cookie, which Streit’s Chief Operating Officer Alan Adler says dates to the early 1950s. Today, Passover is the most-observed holiday on the Jewish calendar, and it seems like almost every food around has become kosher for Passover.

“Every year there are new products,” says Rabbi Moshe Elefant, COO of OU Kosher who has been with the organization since 1987. According to statistics compiled by Lubicom Marketing Consulting, LLC, the kosher food industry marketing consulting group, around 200 new Passover products hit supermarket shelves each year, many of them falling into the category of “nosh.”

“I remember when potato chips first became kosher for Passover,” says Rabbi Elefant wistfully. “Now you can find almost every variety of candy, gum, even pretzels.”

Fueling this change are the Chassidim, who comprise a large percentage of the kosher-food-buying public. “In the past, Chassidim bought relatively few products for Passover. Today they buy many products,” says Rabbi Elefant. In other words, the Chassidim have made the switch that other American Jews made decades before—they’ve turned Passover into a store-bought holiday too, and the market has shifted to accommodate their needs.

For much of history, Jews subsisted on matzah and potatoes on Passover; nowadays, there’s kosher for Passover pretzels, granola and even pizza!

Unlike Sephardic and some Ashkenazic Jews, Chassidic Jews traditionally refrain from eating “gebrokts,” or matzah that has been mixed with liquid.

“In the last five years, manufacturers that once made their products with matzah meal now make them with potato starch and other non-gebrokts ingredients,” says Rabbi Elefant. He cites two major bakeries, Schick’s and Osem, both of which have removed matzah meal from their Passover baked goods. “Osem even printed the blessing Shehakol instead of Mezonot on the packaging to let people know [to recite the correct blessing over the product].”

Interestingly, the trend away from gebrokts also dovetails with another major food trend: the preference for gluten-free products. Gluten is a protein compound that gives dough elasticity, but for people with celiac disease and other stomach problems, it is hard to digest. Non-gebrokts products are wheat free and gluten free, and as the number of people refraining from gluten grows, so does the market for foods that are non-gebrokts. At this year’s Kosherfest, the kosher food industry’s annual trade fair, manufacturers displayed muffins, cakes, flatbreads, crackers and even granola bars made gluten free with potato starch and tapioca blends replacing matzah meal.

The other major change is in the increased range of wines. Forget old-fashioned raisin wine and sweet Seder wine “so thick you could cut it with a knife,” in the words of an old advertisement for a now-defunct sweet wine. “Today we have connoisseurs. There are people who are prepared to spend hundreds of dollars on a bottle of wine,” says Rabbi Elefant.

Kosher wine now exists in all varieties: Merlot, Syrah, Semillions, Rose, Chardonnay, Riesling and more. “Wherever wines are manufactured, you can find kosher wine,” says Rabbi Elefant. “In Israel there are 150 wineries and their number is increasing.”

Of course there are still purists who make their Passover foods at home as their grandmothers did. And there are others who eschew the ever-growing Passover supermarket aisle for the delights of yet another twenty-first-century luxury—the Passover hotel.

Notes

1. Gil Marks, Encyclopedia of Jewish Food (New York, 2010), 532.

2. Ibid, 508.

3. New York, 1996.

4. John Cooper, Eat and Be Satisfied: A Social History of Jewish Food (New Jersey, 1993), 194.

5. Herbert C. Dobrinsky, A Treasury of Sephardic Laws and Customs: The Ritual Practices of Syrian, Moroccan, Judeo-Spanish, and Spanish and Portuguese Jews of North America (New Jersey and New York, 1986).

6. http://halachicadventures.com/the-4452-year-old-food-by-Jenna; Jenna Weissman Joselit, The Wonders of America, Reinventing Jewish Culture 1180-1950 (New York, 1994), 219.

Carol Ungar is a full-time mother and freelance writer living in Israel. Her work has appeared in the New York Jewish Week, Tablet, the Jerusalem Post and other publications and web sites.