On January 1, 2020, over 100,000 Jews gathered at MetLife Stadium and the Barclays Center to celebrate the thirteenth Siyum HaShas. It was a day of joy; of crowning achievement; of proud identification as Jews; a public proclamation of how limud haTorah has permeated and uplifted our community and defines our essence; a day of prayer and thanks to Hakadosh Baruch Hu. And it was also a day to remember, to proclaim our ability not only to survive but to thrive, a day to celebrate our eternity. The Siyum HaShas included a remarkably moving presentation by Rabbi Paysach Krohn (youtube.com/watch?v=X04xDtlQ9c0) regarding what has come to be known variously as the DP Camp Gemara, the Survivors’ Talmud, or the She’erit Hapleitah Shas. At the Siyum, an actual volume of that historic Shas was used to be mesayem (conclude) the Daf Yomi cycle.

On January 1, 2020, over 100,000 Jews gathered at MetLife Stadium and the Barclays Center to celebrate the thirteenth Siyum HaShas. It was a day of joy; of crowning achievement; of proud identification as Jews; a public proclamation of how limud haTorah has permeated and uplifted our community and defines our essence; a day of prayer and thanks to Hakadosh Baruch Hu. And it was also a day to remember, to proclaim our ability not only to survive but to thrive, a day to celebrate our eternity. The Siyum HaShas included a remarkably moving presentation by Rabbi Paysach Krohn (youtube.com/watch?v=X04xDtlQ9c0) regarding what has come to be known variously as the DP Camp Gemara, the Survivors’ Talmud, or the She’erit Hapleitah Shas. At the Siyum, an actual volume of that historic Shas was used to be mesayem (conclude) the Daf Yomi cycle.

The story of the printing of the Survivors’ Talmud is a remarkable testament to the enduring emunah of the few who survived Churban Europa, and who sought to recreate organized Jewish life, ritual observance and Torah learning in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust.

Following the end of World War II in Europe, thousands of Jewish survivors of the Nazi extermination camps were relocated to displaced persons (DP) camps until arrangements could be made for them to be reunited with family, or they would otherwise be able to leave Europe. The number of Jewish inhabitants of the DP camps in the zones of occupation ranged from 50,000 in May 1945 to 185,000 by late 1946. These survivors, the She’erit Hapleitah, arrived in the DP camps with only the clothes on their backs, their bodies wracked by disease, their souls shattered by the unspeakable horrors they had suffered and witnessed. As the hope of finding surviving relatives gradually diminished, and the extent of the near total destruction of European Jewry became increasingly apparent, it was an indomitable faith that guided—indeed propelled—the rebirth of Jewish life.

Responsibility for these survivors, and the DP camps that housed them, fell to the US Army, with help from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (the Joint). Of course, it would be some time before all of the survivors could be resettled, and in the interim, the Jews living in the DP camps began to organize some semblance of the religious life and infrastructure that had been eradicated under Nazi control. The ability to once again engage in limud Torah was a yearned-for priority. Among the many struggles and difficulties facing them, the survivors in the DP camps had barely any sefarim, save for the few that had been stashed in German warehouses and a number of volumes loaned by the Joint and the American Vaad Hatzalah (formed by the Union of Orthodox Rabbis in America and Canada). For the survivors, the return to a meaningful life of Torah study was paramount; this required access to sefarim.

A dedicated group of Jews led by Dachau death camp survivors Rabbi Shmuel Abba Snieg, chief rabbi of the US zone of Allied-occupied Germany, and Rabbi Samuel Jakob Rose, a student of the famed Slabodka Yeshiva, approached the US Commander of the American zone, General Joseph McNarney, and discussed the need to arrange for the publication of the Shas for the survivors living in DP camps. Remarkably, in an inspirational case of Jewish unity, Rabbi Snieg was able to connect across denominational lines with Rabbi Phillip S. Bernstein, a Reform rabbi from New York who was serving as an advisor to General McNarney. Rabbi Bernstein orchestrated a meeting between General McNarney, Rabbi Snieg and his group. In a memorandum to the General, Rabbi Bernstein captured the intense thirst that the Jews of the DP camps had for a Shas: Could General McNarney, acting on behalf of the US Army, provide “the tools for the perpetuation of religion, for the students who crave these texts?” An edition of Shas, Rabbi Bernstein argued, printed right after the horrors of the Holocaust, “published in Germany under the auspices of the American Army of Occupation, would be an historic work.”

It is clear that the rabbis recognized that this project would send a profound message: having the US Army print a set of Shas in Germany would constitute a concrete manifestation of Jewish survival, despite the now apparent, multi-year Nazi effort to exterminate the Jews, their culture and their religion. General McNarney, for his part, immediately understood the significance and potential impact of this project. Despite severe shortages of paper, ink and supplies, General McNarney ordered the project’s start. An agreement, titled “The Agreement Between the American Joint Distribution Committee and the Rabbinical Council, US Zone Germany, Regarding the Printing of the New Edition of the Talmud,” was drafted and signed on September 11, 1946. The Joint would supervise the project alongside the US Army, while the funding would come from the Joint and the German government. Because of the dearth of supplies, as well as the Army’s underestimation of how many sets of Shas would be needed in the camps, the original approval was for fifty copies of the Shas.

With every breakthrough in the quest to bring the Survivors’ Talmud to fruition, a major obstacle arose. Foremost among the challenges was the inability to locate a complete set of Shas in post-War Europe. Between 1930 and 1945, the Nazis had stolen or burned countless sefarim belonging to European Jews (according to published estimates, the Nazi machinery confiscated between three and four million Jewish books); and throughout the entire region, not one complete set of Shas could be found. Ultimately, two original sets were brought from New York by the Joint, but only after Rabbi Snieg and Rabbi Rose discovered hidden copies of Masechet Nedarim and Kiddushin in their DP camp, itself a remarkable testament to the dedication to Torah learning amidst the depravity of the Holocaust.

Rabbi Samuel Jakob Rose, a survivor of Dachau, examines the galleys of the first postwar edition of the Talmud to be printed in Germany. Photo taken ca. 1947. Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum via the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

By February of 1947, work on the printing of the Survivors’ Talmud began, under the direction of Rabbi Snieg and Rabbi Rose. The Army had requisitioned a printing plant in Heidelberg, Germany for printing the Survivors’ Talmud—ironically, this same plant had mass-produced Nazi propaganda literature during the war years. Many additional obstacles followed, including scarce materials, delays in funding from the German government, and long waits for supplies being shipped from overseas. At long last, the first copies were printed in May of 1949. At an emotional ceremony, Rabbi Snieg presented the first copy of the Shas to General McNarney’s successor, General Lucius Clay, famously stating: “I bless your hand in presenting to you this volume embodying the highest spiritual wisdom of our people.”

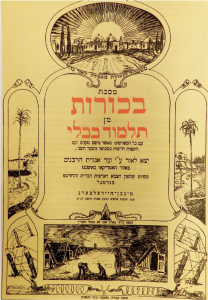

The final printing was completed in November of 1950, bringing the total number of sets to just a few hundred. This was the one and only instance in modern history that a national governing body had published an entire edition of Shas. Each volume of the Survivors’ Talmud was printed with its now-famous title page, depicting a Nazi concentration camp enveloped in barbed wire. Above the camp are scenes from Israel: palm trees and holy sites. Connecting the two contrasting images are the words (in Hebrew) “from bondage to freedom, from darkness to a great light.” In a brief introduction, Rabbis Snieg and Rose told the story of the publication of the She’erit Hapleitah Shas:

Engraved in our memories is that bitter day in the ghetto, when the decree came from the Nazis, may their memory be blotted out, to gather up all the books into one place to destroy them. The peril of death hung over those who would dare hide a book . . . All our holy books were taken from us for abuse and set afire. Now, because of Hashem’s great mercies, a remnant of His people remains, saved from the sword of their accursed destroyers, but without a book in their hands . . . during our overlong exile, our holy books were burned once and again by monarchs and governments. This is the first time in the long history of the Jewish people, that a government has helped us to publish the books of the Talmud, which are our life and length of days.

The volumes of the Survivors’ Talmud came with an English dedication, signed by Rabbi Snieg:

This edition of the Talmud is dedicated to the United States Army. The Army played a major role in the rescue of the Jewish people from total annihilation and after the defeat of Hitler bore the major burden of sustaining the DPs of the Jewish faith. This special edition of the Talmud published in the very land where, but a short time ago, everything Jewish and of Jewish inspiration was anathema, will remain a symbol of the indestructibility of the Torah. The Jewish DPs will never forget the generous impulses and the unprecedented humanitarianism of the American forces, to whom they owe so much.

In so many ways, Yiddishkeit is built around the obligation to constantly remember: “Zachor et yom haShabbat lekadsho”; “Zachor et asher asa lecha Amalek”; “Zecher li’Yetziat Mitzrayim”; Yom Hazikaron; Zichron teruah; Zecher l’Mikdash k’Hillel. Over and over—every Shabbat and every chag—we are commanded to remember some critical event in the history of our people. No other religion that I am aware of gathers communally even once, let alone four times each year, to formally remember loved ones who are no longer with us. Yizkor is a cornerstone of our ritual, and a fundamental element of being a Jew. Jews are obliged to remember. But how is this obligation to remember actualized? Perhaps most challenging of all: how are we to remember that which we have never personally experienced? The Pesach Hagaddah seeks to confront this fundamental dilemma: “Bechol dor vador chayav adam lirot et atzmo k’ilu hu yatza miMitzrayim—In each and every generation, one must view himself as if he personally had gone out of Egypt” (Pesachim 116b).

The title page of Masechet Bechorot from the “Survivors’ Talmud.” Courtesy of Yeshiva University, Mendel Gottesman Library

We endeavor, to the maximum extent possible, to relive a past event with which we have no direct, personal relationship. But how can we ever transcend our own environment and truly relate to another era, or to profoundly different circumstances? As it relates to the Holocaust, our generation is particularly challenged in remembering a past that we have thankfully never experienced. It is a challenge that, I believe, consumes our rebbeim and teachers. How to teach memory. That challenge multiplies with each passing year, as the number of Holocaust survivors dwindles, and few remain to speak firsthand of the horror and the torment. The obligation to remember becomes all the more immediate and all the more critical.

Perhaps we can gain some insight from the paradigm mitzvah of remembering: “Zachor et asher asah lecha Amalek baderech b’tzeitchem miMitzrayim . . . lo tishkach—Remember what Amalek perpetrated against you when you were going out of Egypt . . . do not forget” (Devarim 25:18-19). Why is it necessary for the Torah to add the words “lo tishkach” —do not forget—when the pasuk begins with the word “zachor,” remember? Why this seeming redundancy?

The Rambam counts two separate mitzvot in relation to remembering Amalek. The first is zachor—zachor b’peh: to remember out loud, by articulation through speech. The second, lo tishkach, do not forget, is balev—an intellectual and emotional memory, a memory indelibly etched in the heart and mind. We are obligated to internalize what the threat of Amalek truly means, to keep that threat in our consciousness and never forget it.

The decision to make the Siyum HaShas on a volume of the Survivors’ Talmud fulfilled both aspects of zachor, lo tishkach. Can any of us truly comprehend, let alone seek to replicate, the emunah in Hakadosh Baruch Hu demonstrated by the She’erit Hapleitah, who struggled to regain their precious sifrei kodesh, who pleaded to once again hold a Shas in their hands? But at the very least we must strive to remember it—we are obliged to remember it—in the fullest, deepest, most profound sense of zachor, lo tishkach.

About eight years ago, my wife and I were searching for a bar mitzvah gift for one of our grandsons—a gift we hoped would convey both meaning and obligation. We happened upon an auction of sefarim and purchased a set of the She’erit Hapleitah Shas. That would be our gift to our grandson. The Shabbat of his bar mitzvah, I addressed our grandson, relating the story of how this Shas came to be printed, and detailing the obligation to remember the courage and the extraordinary faith of those who yearned for its publication. I concluded with the following thoughts, which I share with all of you:

“Remembering the past does not mean approaching life weighed down by tragedy; quite the opposite: it means being uplifted by our capacity for survival. I think Elie Wiesel expressed this concept best in a lecture he gave in 1986, on the occasion of his receiving the Nobel prize. He said:

‘Because I remember, I despair.

Because I remember, I have the duty to reject despair.’

Dr. Erica Brown, in her collection of essays called In The Narrow Places (Jerusalem/New York, 2011) for the Bein Hametzarim period, writes as follows:

‘As Jews, we never dwell on the persecutions of the past without opening our arms wide to the promise of the future. Rav Soloveitchik once questioned the implications of the medrash on Bereishit that states that God created numerous worlds and then obliterated them, before creating the universe as we know it. The Rav’s response: a Jew has to know how to emulate God and, like God, to continue to create even after his former world has been eradicated. It is that persistent sense of hope and recreation, despite suffering and destruction, that gives us the strength to remember, to transform memory into action, misery into repentance, and desolation into redemption.’”

Concluding my words to my grandson, I said: “We hope you will use this Shas often and that it will help you to be mekayem both mitzvot of remembering—zachor and lo tishkach. We hope that you will have the zechut to complete multiple masechtot . . . and we hope that on each occasion when you make a siyum, you will remember and honor the memory of those who first held this Shas—remembering verbally—zachor—and remembering in your heart and mind—lo tishkach.”

As we did at the recent Siyum HaShas, we honor memory, while rejoicing in the present and boldly and confidently anticipating a future that, with God’s help, is ours to forge. As Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks recently remarked:

“I believe that we must honor the past but not live in it. Faith is a revolutionary force. God is calling to us as once He called to Moses, asking us to have faith in the future and then, with His help, to build it.”

Allen I. Fagin is executive vice president of the OU.