Hyper-connected as we are today to multimedia sources of information, with global news instantaneously available at our fingertips, it takes a leap of imagination to appreciate what newspapers and journals meant to people in generations long gone by. The periodical that arrived in the post or that was purchased from the newsagent brought tidings and vital information to the thirsty homebound reader eager to hear of the welfare of kith and kin, to discover what was transpiring in faraway lands or to be emotionally transported by tales and stories of the great wide world.

The nineteenth century—particularly from the 1830s onward—saw an efflorescence of Jewish newspapers and journals throughout Europe and extending to the Caribbean and North America. Some scholars speculate, quite plausibly, that the tragic unfolding of circumstances surrounding the 1840 Damascus blood libel served as an impetus for the increase in newspaper coverage of foreign events. A truth was impressed upon Jewish communities worldwide with forceful clarity: Scapegoating, fabricated charges and torture could be curtailed if only accurate factual reports reached major centers of population and nefarious persecution was exposed.1

The development of a vibrant Jewish periodical literature was significant for a reason beyond providing knowledge of unfolding events. During a period of intellectual, political, social and religious ferment, it was in the pages of the printed journals, the Zeitschriften, that passionate debates and arguments, visions and counter-visions were presented, scrutinized, contested and subjected to seemingly endless analysis.

For a people intoxicated by printer’s ink it should not be surprising that, concurrent with many genres of daily, weekly and monthly papers and journals that became commonplace in Europe, a colorful and variegated literary periodical scene emerged in Jewish enclaves. Peri Etz Chayim, a Hebrew monthly featuring rabbinic halachic rulings, appeared in Amsterdam from 1728 to 1761 and is generally regarded as the earliest magazine-type Jewish journal. Other pioneering Hebrew-language endeavors were the two issues of Moses Mendelssohn’s Kohelet Mussar (1750) and HaMe’assef (1784), the more successful monthly literary organ of his disciples. By the early decades of the next century many of the newly-established periodicals were in languages other than Hebrew, with the preponderance appearing in German. A Jewish-themed press began to flourish in Austria, France (the celebrated Archives Israélites de France), England and Holland. In the 1840s the Western Hemisphere witnessed the appearance of The Occident in Philadelphia (1843-69) and First Fruits of the West (1844) in Jamaica followed by several other ventures, while the next decade saw the inauguration of a plethora of Jewish publications in Germany, Hungary, Romania, Italy, Galicia and Russia.

Singularly noteworthy was the partisan role of this press in which distinctively denominational journals played an all-important role in the turbulent religious life of local communities. With the growth of the Reform movement in the nineteenth century, factionalism became a hallmark of Jewish life. By the second decade of the century, the ideological cleavage within the ranks of Judaism had become pronounced; Orthodoxy and Reform emerged as distinct factions pitted against one another in a struggle for supremacy. The fierce ideological controversies and communal political struggles they spawned played themselves out dramatically in the pages of the periodical literature. Strident pleas for change and innovation were penned in a variety of Reform-sponsored journals beginning with the early monthly, Sulamith (1806), and later in Ludwig Philippson’s more moderate Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums (est’d. 1837) and the radical Der Israelit des Neunzehnten Jahrhunderts (1839-1848). It was into this lively, pulsating literary arena that a fledgling Orthodox journal, Der treue Zionswächter (The Faithful Guardian of Zion), plunged in 1845.

Front page of the first issue of Der treue Zionswächter, July 3, 1845. Rabbi Ya’akov Ettlinger initiated the weekly magazine for the purpose of spreading Torah ideology in the vernacular German—a radical move at the time.

All images in this article are from JCS Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main/Digitale Sammlung Judaica (sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/cm/nav/index/title).

One cannot overemphasize the impact at that juncture of Jewish history of the appearance of a German-language journal that was unabashedly devoutly Orthodox in orientation. By then, fluency in the vernacular had come to be regarded as an emblematic criterion of eligibility for civil rights. Even Mendelssohn, the rationalist, was so biased in his criticism of the Yiddish of his coreligionists that he had written, “I fear that this jargon has contributed not little to the immorality of the common man; and I expect a very good effect from the increasing use of the pure German idiom.”2 The disdain evident in this illogical reasoning was echoed in many screeds against the Orthodox.3

In their endeavor to bolster the Orthodox sector of the community and to repel further encroachments of Reform, Orthodox leaders were anxious to rehabilitate the image of traditional Judaism in the public eye and to dispel the notion that their rabbinate was culturally primitive, unenlightened and uninformed.4 They realized that a major impediment to their efforts had been the failure to address the youth in a language they understood.

One of the earliest Orthodox scholars to preach in German, Rabbi Ya’akov Ettlinger, a preeminent halachist, later renowned as the author of Talmudic novellae Aruch laNer and Teshuvot Binyan Zion, was committed to harnessing the vernacular, both spoken and written, to propagate the ideology of Torah. In response to the first Reform rabbinical conference (1844), Rabbi Ettlinger became determined to publicize a formal protest. In order to gather as many Orthodox signatures as possible, he composed a text in German and circulated it among his colleagues. Rabbi Abraham Samuel Benjamin Sofer, the Ktav Sofer, hesitated to sign a German text and, accordingly, following his recommendation, an amended document, a manifesto entitled Shelomei Emunei Yisra’el, was published in 1845 as a Hebrew text accompanied by a German version and appended rabbinic signatures.5 The importance of employing the vernacular is reflected in a published Reform rejoinder whose author jeeringly remarked: “Do count your men! How many among them understand German?”6

Indeed, a crucial turning point in the Orthodox response to the challenge of Reform was the reaction to the Reform rabbinical conferences of 1844, 1845 and 1846 as heralded by the publication of Shelomei Emunei Yisra’el. Although the manifesto itself had little impact, it reflected a new mindset. Awareness that the partisans of Reform had now constituted themselves as an organized and militant movement, Orthodox leaders awakened to the reality that a passive stance, negativity, condemnations and bans would not further their cause. The need of the hour was for concerted action, a program of positive activities in the areas of education, synagogue decorum, social agencies and, above all, mass communication.

The Zionswächter, the periodical founded in Altona by Rabbi Ettlinger, was published as a weekly from July 3, 1845 until June 28, 1850. After a hiatus of a year, the journal resumed publication and appeared again, as a bi-weekly with fewer pages, from July 4, 1851 until early in 1856.7 A Hebrew supplement, Shomer Zion haNe’eman, was published fortnightly from July 1, 1846 until March 28, 1856, with an interruption of one year (July 5, 1850 to July 11, 1851). In all, two hundred and twenty-two issues of the Hebrew supplement were published. Rabbi Ettlinger engaged the services of Rabbi Dr. Samuel J. Enoch as editor of these periodicals. At the time, Rabbi Enoch was the director of the Altona Talmud Torah, and played a prominent role in communal and charitable affairs. In 1856 Rabbi Enoch was called to the rabbinate of Fulda. Apparently, cessation of publication of the Hebrew periodical that year was the result of Rabbi Enoch’s departure for Fulda.

Throughout the duration of its publication, the Zionswächter served first and foremost as an apologia for Orthodoxy. Countless articles were devoted to discussions of the role of religion in the modern world, the evolving nature of the rabbinate, the selection of candidates to fill rabbinic positions, the new functions of various communal institutions and changing family dynamics. Orthodox response to the challenge of political emancipation and assertion of the patriotism of the Orthodox community were recurring themes. From the very inception, considerable space was devoted to matters pertaining to education. An attempt was made to analyze the effects of political developments on the evolution of the German educational system and to examine the merits of separation of church and school. Elementary schools, high schools, seminaries for the training of teachers and rabbis, yeshivot and adult education were the subject of numerous contributions.

Much attention was focused on the major halachic controversies of the time, with particular emphasis on attacks on circumcision and metzitzah as well as on halachic problems stemming from the proliferation of civil marriage. While at times echoes of the bitter conflicts between Reform and Orthodox protagonists reverberated in the pages of the journal, there was a distinct endeavor to maintain the discussion on a dignified level and lapses into invective and strident partisanship were rare.

The nineteenth century, particularly from the 1830s onward, saw an efflorescence of Jewish newspapers and journals throughout Europe and extending to the Caribbean and North America.

The magazine published brief articles on Jewish history written in a popular style and short biographies of historical personalities, such as Saadia, Ibn Ezra, Maimonides and Abravanel. Poetic translations as well as original verse were also a regular feature of the magazine. Many issues contained selections from the liturgy rendered into German verse. Noteworthy was an attempt to harness the journal as a means of aiding Sabbath observers in their efforts to obtain employment as well as the magazine’s role in promoting charitable endeavors and centralizing charitable collections.

The favorable reception that greeted the German journal encouraged Rabbis Ettlinger and Enoch to publish a Hebrew supplement, Shomer Zion haNe’eman, as well. The Hebrew journal was designed to fill a void in the intellectual life of the Orthodox community. It was envisioned that the availability of a forum for publication would foster an atmosphere of study and scholarship and would encourage formulation of reasoned responses to the novel questions of Jewish law and ethics which were the product of the modern age. Rabbinic scholars were indeed quick to endorse the new literary undertaking and the periodical soon boasted an impressive roster of contributors. Articles were authored by prominent rabbis residing in Germany, Hungary, France, Poland and Palestine. The publication succeeded in generating a lively exchange of ideas among the various contributors. Frequently, discussion of a particular topic would continue over several issues with various scholars presenting their views with regard to the particular problems raised. The scholarly debate encouraged by the publication was one of its most valuable achievements and served to enhance the prestige of Talmudic study.8 Remarkable in a rabbinic journal of this genre was its orientation toward modern critical scholarship and the publication of numerous manuscripts of medieval scholars. The editors were also eager to foster study of the Hebrew language and declared their wish to contribute to the enhancement of Hebrew literary style and their “desire to disseminate over the face of the world . . . the light of our holy language from its hidden treasures.”9

Rabbi Ettlinger considered belief in the restoration of Zion to be at the heart of a Jew’s faith. It was the anticipation of Israel’s spiritual rebirth as foreseen by the Prophets that sustained Israel throughout the centuries. Any attempt to eradicate this belief would constitute a mortal blow to Jewry. In his anti-Reform polemics, Rabbi Ettlinger reiterated his conviction that rejection of the belief in the restoration of Zion was the symbol of the final parting of the ways. The very choice of the name “The Faithful Guardian of Zion” for both his German and Hebrew publications indicated that he deemed belief in Zion to be an issue of central importance. It was in defense of that doctrine that the ramparts must be manned.

In both journals, matters relating to the welfare of the Holy Land were featured prominently. Articles concerning Palestine published in the Zionswächter fell into three categories: news items, descriptions of conditions in the country and appeals for funds. During the period of more than ten years in which the Hebrew Shomer Zion haNe’eman was published, it was instrumental in forging links between members of the scholarly community in the Holy Land and their colleagues in Europe. The importance of both this Hebrew journal and its German-language counterpart in strengthening the bonds between the Jews of Palestine and the diaspora should not be underestimated.

Assessment of the Zionswächter’s success depends upon one’s vantage point. The columnists of the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums tended to view the Zionswächter with a measure of disdain. Yet on a very fundamental level, this Orthodox journal did meet the challenge of the Reform publications: It was written in fluent German and its table of contents included belles lettres, poetry and scholarly essays. Numerous scholarly works were authored by leading exponents of the Wissenschaft des Judentums; but learned tomes were not the appropriate means for the dissemination of new ideas among the masses. Newspapers and journals, with their lighter style, briefer articles and periodic exposure, provided ideal media for publicizing and popularizing religious innovations. To be sure, for a great number of readers these periodicals were of interest primarily as sources of information, diversion and entertainment and only secondarily for their theological content. Yet, precisely because the influence was subtle and indirect was its effect more pronounced. Thus, for example, the Allgemeine Zeitung enjoyed unusual success on the popular level and consequently was one of the most powerful instruments for advancing Reform ideology. Until the appearance of the traditionalist publications fostered by Rabbi Ettlinger, no comparable media were available to the Orthodox. The Zionswächter and Shomer Zion haNe’eman were significant, not so much because they presented a response to the view of Reform, but because they provided the Orthodox public with alternative reading material. They were effective primarily for their role in the struggle of the Orthodox for containment of Reform, rather than as a means of spreading Orthodoxy among those who had left the fold.

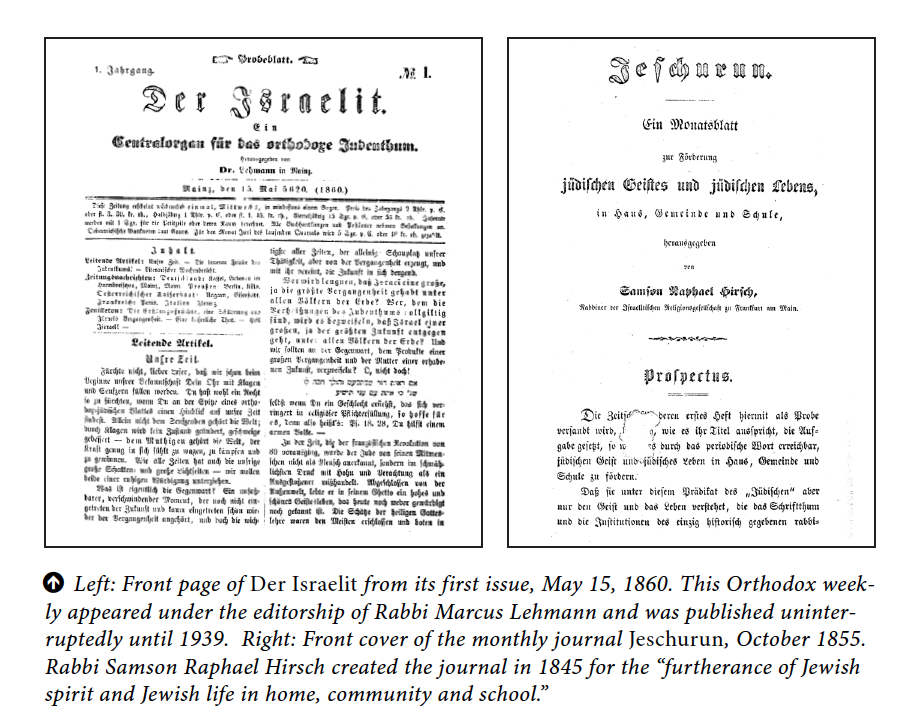

The pioneering work of Rabbis Ettlinger and Enoch convinced the Orthodox of the crucial role played by the communications media in the modern world. Shortly before the Zionswächter ceased publication, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch announced his intention to found a new Orthodox journal devoted to the “furtherance of Jewish spirit and Jewish life in home, community and school.” This periodical, a monthly called Jeschurun, was published from October 1854 to September 1870. Jeschurun served as a forum to disseminate Rabbi Hirsch’s own views as well as articles and news of general interest to the Orthodox community. A publication which was destined to have a greater impact on the wider community was Der Israelit, an Orthodox weekly which first appeared on May 15, 1860 under the editorship of Rabbi Marcus Lehmann and was published uninterruptedly until 1939. A more direct chain of influence may be traced from the Altona periodicals to another important journalistic venture. In June 1870, at Rabbi Ezriel Hildesheimer’s initiative, an Orthodox weekly, Die jüdische Presse, was founded in Berlin. In an article appearing in its second edition, June 24, 1870, Rabbi Hildesheimer noted that Die jüdische Presse was the spiritual heir of the Zionswächter. In the spirit of its predecessor, Rabbi Hildesheimer declared, Die jüdische Presse would be dedicated to the interests of “true Judaism” and would endeavor to serve as a “guardian of Zion.” One of the most striking resemblances in the editorial policy of the two periodicals was the positive manner in which both journals addressed themselves to questions relating to the Land of Israel.

With the proliferation of periodicals, newspapers and online forums in our own day, there is one particular aspect of the earliest Orthodox publications that merits attention. The authors of the manifesto Shelomei Emunei Yisra’el opened their proclamation with a citation of Ezekiel 33:7, “So you, O son of man, I have set you a watchman unto the House of Israel” and incorporated in the masthead of each issue of Shomer Zion haNe’eman were the words “Founded by an association of rabbis and scholars standing in the breach and guarding the holy charge.” Clearly, there was an understanding and appreciation of the awesome power of the written word and the concomitant responsibility incumbent on writers and publishers.

It is related that one evening, the Chassidic sage Reb Naphtali of Ropshitz met a watchman making his rounds and asked him, “For whom are you working?” After answering, the man turned to the rabbi and inquired, “And you, for whom are you working, Rabbi?” The Ropshitzer was thunderstruck. He walked alongside the man for a bit and then asked him, “Will you work for me?” “Yes,” the man responded, “I should like to, but what would be my duties?” “To remind me,” responded Reb Naphtali, “to remind me.”

Notes

1. See, for example, Baruch Mevorah, “Effects of the Damascus Affair upon the Development of the Jewish Press 1840-1846” (Hebrew), Zion, 23-24 (1958-59), 46-65.

2. Schriften, V, 605, cited in Michael A. Meyer, The Origins of the Modern Jew: Jewish Identity and European Culture in Germany, 1794-1829 (Detroit, 1967), 44.

3. Cf. Naphtali Hertz Wiesel, Divrei Shalom veEmet (Vienna, 1806), 15-17 and Eliezer Lieberman, Or Nogah (Dessau, 1818), pt. 1, 8-9.

4. Reform protagonists frequently branded the Orthodox as “stillständler” (immobile) and mocked them as backward and primitive. See, for example, W. Gunther Plaut, The Rise of Reform Judaism (New York, 1963), xxiii.

5. See Iggerot Soferim, ed. Solomon Schreiber (Vienna and Budapest, 1933), section 3, no. 5, p. 6.

6. Abraham Adler, Sendschreiben an die sieben und siebzig sogenannten Rabbiner die durch Verdächtigung und Verläumdung zu gewinnen wähnen (Worms, 1845), 6.

7. See Rabbi Yehudah Aharon Horovitz, “Mi’Toldot ha’Mechaber,” in She’eilot uTeshuvot haAruch laNer (Jerusalem, 1989), I, 35 and ibid., note 2. It is unclear whether the date Horovitz gives for the final issue of the German publication is correct. Cf., Richard Gottheil and William Popper, “Periodicals,” Jewish Encyclopedia (New York, 1906), IX, 604, who give 1855 as the date. The final issue included in the Compact Memory Collection is dated December 29, 1854.

8. From the very outset, the German-language journal was focused on defense of Orthodoxy and negation of Reform whereas its Hebrew supplement, while equally devoted to those goals, was more positive in orientation. It is not surprising that, as a result, the German journal contains but few contributions of either literary or scholarly import. Yet, the Hebrew journal is replete with articles of lasting value. Many of the responsa published therein were subsequently included in responsa collections and were cited in the works of later rabbinic scholars. Consequently, a demand for copies of issues of this journal continued long after they ceased to circulate and caused them to become collectors’ items. The republication of Shomer Zion haNe’eman in New York, 1963, is evidence of its enduring interest and value as a rich treasury of Jewish scholarship.

9. No. 106. An editorial note concludes: “For only in the aggrandizement of Torah and the flowering of the idiom of our language will the faithful guardians of Zion achieve their desire.”

Dr. Judith Bleich is a professor of Judaic studies at Touro College in New York.

Articles in this cover story:

The Burgeoning Chareidi Print Media by Hillel Goldberg

Women in Orthodox Media: Meet some of the women who are shaping and influencing the Orthodox world

Managing Mishpacha by Bayla Sheva Brenner

Rochel Sylvetsky: From Community Activist to Editor of Leading News Site by Toby Klein Greenwald

Sivan Rahav-Meir: Orthodox With a Hashtag by Toby Klein Greenwald

Rechy Frankfurter: Ami’s Woman at the Helm by Bayla Sheva Brenner

The Jewish Observer: Champion of the Orthodox Right by Zev Eleff

Discussing Journalism and Jewish Law with Rabbi J. David Bliech by Binyamin Ehrenkranz