Some personal memories of landmark historical moments.

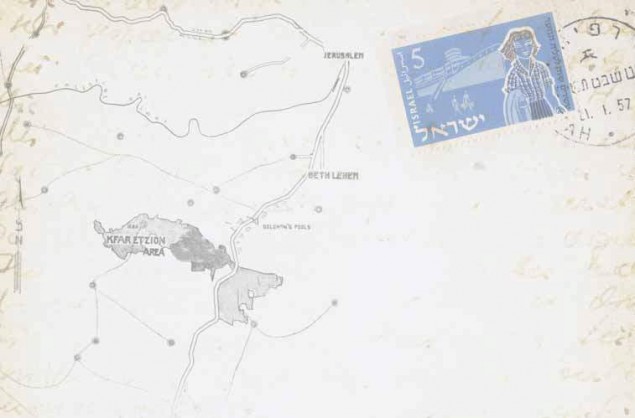

Map of Gush Etzion, 1947: Some twenty kilometers from Jerusalem, nestled between Bethlehem and Hebron and among numerous Arab villages, were the four kibbutzim of Gush Etzion: Kfar Etzion, Massuot Yitzchak, Ein Tzurim and Revadim. Today, Gush Etzion consists of seventeen communities and nearly 40,000 residents.

Map of Gush Etzion, 1947: Some twenty kilometers from Jerusalem, nestled between Bethlehem and Hebron and among numerous Arab villages, were the four kibbutzim of Gush Etzion: Kfar Etzion, Massuot Yitzchak, Ein Tzurim and Revadim. Today, Gush Etzion consists of seventeen communities and nearly 40,000 residents.

November 1967. It was a cold, drizzly Friday in Jerusalem. My friend Chana Porath (Idles) and I had been invited to Kfar Etzion by Chaim Mageni, an American we knew who had decided to make his home in the fledgling kibbutz. The children of those ruthlessly murdered in the Kfar Etzion Massacre during Israel’s War of Independence had returned to the newly captured kibbutz several months earlier. (See sidebar on the siege of Gush Etzion.) The euphoria following the Six-Day War had deeply impacted the country.

I was eighteen-years-old at the time, a student at Machon Gold, and already one of the myriad of students and volunteers from abroad who decided that we had landed in the lap of history and would be remaining in Israel when our studies or tours of duty were over.

There were no buses to Kfar Etzion. We met a kibbutz member, Moshe, at a little store called Biederman’s on Havatzelet Street, in the center of Jerusalem. This was the pick-up location for supplies and Shabbat visitors. We were told that it had served the same purpose in the 1940s, when Gush Etzion was a vibrant, growing bloc of four kibbutzim. (Kfar Etzion was the first kibbutz, established in 1943). We drove silently in the little tender as it traveled through Bethlehem, then wove along the swerving, narrow road between the low mountain terrains that was, at the time, the only paved road to the Gush. The fog was so heavy that we prayed that Moshe knew the road well enough to drive it blindly.

All of the buildings on the kibbutz, save one, had been destroyed by the Jordanians when the Gush fell in May 1948. A pre-fab, all-purpose shul/dining hall/kitchen/meeting room had been hastily erected in the heart of the kibbutz when the children returned, and that was where the life of the community took place. A charismatic twenty-three-year-old student of Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav conducted some of the tefillot, led zemirot and gave a rousing devar Torah at the Shabbat meal. Our host told us, “That’s Chanan Porat.” He was mesmerizing then, and that quality never left him, even when he was close to death. He was the undisputed spiritual (and to a certain extent, practical) leader of the kibbutz. His vibrant belief and description of the geulah, redemption, in which the children of Kfar Etzion were playing a part, permeated the post-war atmosphere and resounded far beyond the hills of the Gush. It was one of the factors contributing to the spiritual awakening during those heady days. I spent every free Shabbat in Kfar Etzion, enthralled by its contagious community spirit. One of the younger kibbutz members, whom everyone just called by his nickname “Topele,” is today more widely known as Rabbi Elyashiv Knohl.

Winter 1972. The Gesher organization had been founded by Dr. Daniel Tropper and was bringing together religious and non-religious high school students in an attempt to bridge the widening gap in Israeli society. One of its first seminars was held in Kfar Etzion. Small kibbutz homes, a larger dining hall and a shul had been built, and the pre-fab hall of 1967 was now the dining hall of the youth hostel. Rabbis Porat and Knohl were among those who spoke to the Gesher youth, inspiring them to at least become familiar with what Torah Judaism had to offer. Rabbi Porat had by now reached beyond the religious world and was inspiring young people throughout the country. He would stay up all night with the teenagers, singing, teaching and speaking with them.

Early Winter 1974. Gush Emunim was founded. Rabbi Porat invited some of us to a parlor meeting in Rechavia at the home of two professors—Sara and the late Avraham Halperin. The other speaker was another legendary hero of the war—Ariel Sharon. They captivated the college students with their vision of settlement throughout the historical Land of Israel. Together they inspired a generation, though their paths would widely diverge in the future.

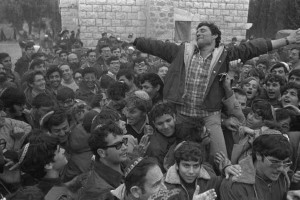

Gush Emunim leader Rabbi Chanan Porat is carried on the shoulders of his followers as they celebrate the agreement which allowed the settlers to stay in Samaria (1975).

Photo: Moshe Milner/Israel Government Press Office

Spring 1974. Large demonstrations were taking place outside the office of the prime minister where Henry Kissinger was pushing for a withdrawal from parts of the Golan Heights that had been captured during the Yom Kippur War. Rabbi Porat wove through the crowd, recruiting people to go to the Golan Heights, to a bunker on the outskirts of Quneitra where members of several local (non-religious) Golan kibbutzim had established a presence to protest the withdrawal. I was one of those on the bus the next morning at dawn. We named our new little community “Keshet.” Rabbi Porat and some of us who were Gesher “graduates” had a dream of creating a community that would be mixed—religious and non-religious. (This never came to fruition.)

Several weeks later, the withdrawal took place and we were relocated to an abandoned plant nursery. We had already lived in the new location a number of days, and my request of the rabbanim leading the community that we put up mezuzot elicited no action. One day Rabbi Porat came to visit and I told him that I was troubled by the situation. He pulled out his wallet, took out a wad of bills and handed them to me. “Then go to Jerusalem and get mezuzot,” he said, which I did. It typified his behavior and was a lesson in life: If you’re not happy with the way things are being done and your requests are falling on deaf ears—just do it yourself. Change things for the better.

Spring 1994. I interviewed Rabbi Porat (and Rabbis Menahem Fruman and Yoel Bin-Nun) for an article in Jewish Action entitled “View from the Settlements” (spring 1994). Rabbi Porat, chillingly prescient, said of the Oslo Accords, “This miserable agreement is a national tragedy . . . it will lead to an armed Palestinian state that will be a landmine in the heart of the State of Israel . . . If the Palestinians don’t get what they want quickly. . . [Arafat’s] divisions will turn to terror . . .” Regarding Shimon Peres’ promises of great economic development in the wake of the agreement, Rabbi Porat said, “The only similarity to economics is that it’s like the stock market—totally ephemeral. Like a bubble, it will burst.” He said that soldiers did not have to obey orders to evacuate settlements, yet also declared, “The red line we must not cross under any circumstance whatsoever is civil war between Jews . . .”

Rabbi Porat recommended that any Palestinian who wishes to be a loyal citizen under Israeli sovereignty should be welcomed, but should also shoulder responsibilities such as national public service. He did not negate the possibility of municipal autonomy for the Arab population, though Israel would be responsible for security. His vision for the future was, “To continue the process of the return to Zion . . . one day the State of Israel will spread from the sea to the Jordan River.”

August 2005. As Sharon, Rabbi Porat’s former confrere, planned and implemented the destruction of Gush Katif, Rabbi Porat led demonstrations against the act which so severely divided Israeli society. My last professional interaction with him was as translator of a book published in 2006 in the wake of the Katif destruction. In the Land of Prayer; Personal Tefillot from Israel in Turbulent Times (reviewed in Jewish Action), edited by Daniel Gutenmacher, included a poem by Rabbi Porat (pp. 136-141).

As one gate is closed to us, open another,

For the day has passed—the final twilight is near,

Hear the weeping of Rachel in the night of stormy tempest,

Take not the mother from her sons

Ten thousand people of every age turned out for Rabbi Porat’s funeral—an event rich with divrei Torah, music and deeply moving hespedim and singing by his friends and family. His twilight arrived, and a new gate opened. I believe he was greeted there by Mother Rachel.

Toby Klein Greenwald is a journalist, educator and community theater director.