The 70 long years of the Babylonian exile had ended. Darius, the benevolent Persian king, son of Queen Esther and King Achashverosh, granted his Jewish subjects permission to return to Zion and rebuild their Temple.1 The Mishnah tells us that the returning Jews made an engraving of Shushan,2 the capital of the Persian Empire, above the newly built Eastern Gateway of the Temple Mount.3 The engraving commemorated the miracle of Purim4 and reminded the Jewish People from whence they came and to remain loyal to their Persian benefactors.5 Because Persia was east of the Holy Land, the Eastern Temple Gateway was chosen as the site for this memorial engraving.6

The 70 long years of the Babylonian exile had ended. Darius, the benevolent Persian king, son of Queen Esther and King Achashverosh, granted his Jewish subjects permission to return to Zion and rebuild their Temple.1 The Mishnah tells us that the returning Jews made an engraving of Shushan,2 the capital of the Persian Empire, above the newly built Eastern Gateway of the Temple Mount.3 The engraving commemorated the miracle of Purim4 and reminded the Jewish People from whence they came and to remain loyal to their Persian benefactors.5 Because Persia was east of the Holy Land, the Eastern Temple Gateway was chosen as the site for this memorial engraving.6

The Talmud also tells us that near the Eastern Gateway was a room in which the national standard of length, the cubit, was engraved upon the wall.7

A medieval Jewish tradition foretells that the prophet Elijah will lead the Mashiach into the Temple grounds through this Shushan Gateway. Elijah is a Kohain and a Kohain may not enter a cemetery. Many centuries ago, some scheming Moslems placed an Arab cemetery along the Eastern Wall to foil Elijah’s plan (Plate #1). However, in the Talmud8 there is a discussion of whether or not a Kohain may enter a non-Jewish cemetery. The sages sought the opinion of the prophet Elijah himself and he ruled that a member of the priestly clan could indeed enter a non-Jewish cemetery. Obviously, the Moslem designer of the cemetery was not a Talmudic scholar.

This Moslem cemetery is built up along the Eastern Wall and completely obscures the remains of the Shushan Gateway from view. Several hundred years ago, a plague in Jerusalem caused the death of many Arabs. The victims of the plague were buried in a mass grave in front of the Shushan gateway and a monument to the tragedy was placed nearby. Over the course of time, the bodies decomposed and compressed, creating a cavern in the cemetery.

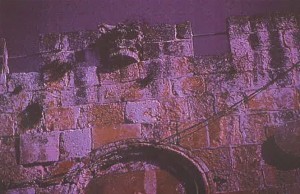

(Plate #2) View inside the cavern. The stones arching upward are built onto the original Shushan Gateway.

The existence of this cavern was not publicized because the Moslems did not want curiosity-seekers trampling through their cemetery. They do not permit non-Moslems to enter those hallowed grounds. Not intending to be disrespectful, I knew that in order to complete my exploration of the walls of Jerusalem, I would need to inspect the cavern on my next trip to Jerusalem.

When I came to the Eastern Wall cemetery, I found that an Arab caretaker was stationed there to make certain no illicit entry would be made. I waited and watched from afar. Around noon, the caretaker decided to take a lunch break. As he walked off to a luncheonette in the Arab village below, I sneaked into the cemetery to the spot where the top of the cavern was located. It was covered over with a rusty metal sheet. After pulling aside the metal covering, I leaned inside the cave. It was pitch black. I began taking pictures at random, unsure of what I was photographing. My work was completed just in time; the caretaker was returning with a metal pipe in hand. I made a hasty retreat.

As soon as I came back to the “States,”9 I had the pictures developed. I could see that the floor of the cavern was littered with the remains of corpses, skulls, and skeletal remnants. More importantly, in the rear of the cavern was an exposed lower portion of the Eastern Wall. On that exposed portion of the Eastern Wall was the upper segment of an arch — the remains of the Shushan Gateway (Plate #2). From that small segment of an arch, I could determine that the original Shushan Gateway was a double gateway, similar to the double Chuldah exit on the Southern Wall.10 With that meager bit of information, I could reconstruct the ancient Shushan Gateway. (See drawing.)

The formation of the cavern also yielded the opportunity to search for the room near the Shushan Gate alluded to in the Talmud which contained the national cubit standard. Such a discovery would resolve once and for all the great halachic debate as to the exact length of the cubit.11 I began to plan my next illegal expedition to the site.

When I arrived there the following year, my great expectations were quickly dashed. The Arabs had filled in the cavern with all sorts of trash and debris. I was not prepared to dig up and cart away several tons of refuse.

When King Solomon built the First Temple, he constructed a special two-chambered building in the Temple compound. One chamber was for bridegrooms and the other was for people observing the traditional period of mourning. Those who participated in the Temple service went to these rooms to offer the appropriate words, either of congratulations or of condolence.12 These rooms were built above the Eastern Gateway and were reconstructed in the Second Temple.13

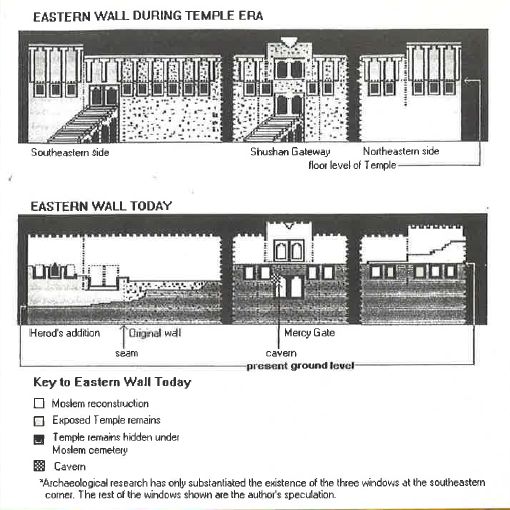

Today, the only visible structure built onto the Eastern Wall is a large building with two sealed arched windows. Christians call it the Golden Gate, but the Jews and Moslems refer to it as Shaar Harachamim, the Mercy Gate (Plate #3). It is decorated with ornate Byzantine stonework similar to the stonework above the Chuldah exit on the Southern Wall.14 In medieval times, when access to the Western Wall was denied to the Jews, they would congregate in front of the Mercy Gate and pray for God’s compassion to redeem His holy nation. Some say that the Mercy Gate is a reconstruction of King Solomon’s two-chambered room.15

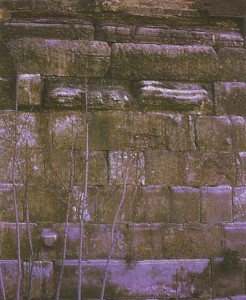

(Plate #4) The vertical line in the center of the photo is the seam, marking the point from which Herod extended the Eastern Wall. The stones to the lower left of the seam are typical Herodian ashlars. The stones to the right of the seam pre-date Herod and are the oldest Temple stones that can be seen.

A few years before the common era, the Judean tyrant, Herod the Great, completely rebuilt the Second Temple and expanded the Temple Mount Compound.16 Herod assembled 10,000 Jewish artisans, 120,000 non-Jewish wood cutters and quarrymen, 50,000 Jerusalemite foremen, and 1,500 uniformed Kohanim and Leviim to oversee the work atop the Temple Mount.17

(Plate #5) The stones projecting from the Eastern Wall were the beginning of an archway which supported a staircase that led to the Temple basement.

At the completion of Herod’s monumental reconstruction project, the Temple Compound was double its original area.18 He relocated the Northern, Western, and Southern Walls further outward. Herod could not move the Eastern wall further out because the Eastern Wall was located near the top of Mount Moriah and the eastern slope was a sharp 300 foot drop downward into the Kidron Valley. However, Herod had to extend the northern and southern ends of the Eastern Wall so it would meet the newly relocated Northern and Southern Temple Walls.

The original Eastern Wall was about 750-1,000 feet long. After Herod’s additions to the wall, it was 1,530 feet long. These additions produced two interesting architectural features. Herod instructed his builders to use a unique design for his Temple stones. The centers of the stones were to be smoothly polished flat surfaces, projecting a fraction of an inch from recessed margins framing the edges. The original Temple stones also had the recessed borders but had rough, unfinished centers projecting out several inches. Much of the Eastern Wall displays these primitive rough Temple stones. But the northern and southern ends of the wall have the smoothly polished Herodian stones.

(Plates #6a, 6b) Two types of building stones. The stone with the weave-like pattern was used in building outside the azarah courtyard. The fragment of splintered stone with the smooth center was used within.

Another architectural feature that was produced when Herod added to the length of the Eastern Wall is a seam. Whenever an extension is built onto a wall, a vertical line, called a seam, remains where the old wall ended and the new construction began. Today, we can see that seam 105 feet from the southern end of the Eastern Wall. We can see the Herodian stones, with their telltale smooth centers, to the left of the seam and the pre-Herodian stones, with their rough protruding centers, to the right of the seam (Plate #4).

Near the southern end of the Eastern Wall are several other intriguing features. The most noticeable is a series of stones projecting out from the wall (Plate #5). This was the beginning of a Temple archway. The archway supported steps that led into the basement of the Second Temple, popularly called King Solomon’s Stables. This archway on the Eastern Wall was directly opposite the archway on the Western Wall referred to as Robinson’s Arch.20 If one looks carefully above the stones of the arch, one can see the outlines of two sealed-up Temple gateways. Again, with some careful scrutiny, one can make out the outlines of three Temple windows, about 40 feet to the left of the two sealed gateways. The middle window has been reconstructed.

Another remarkable feature is found about 50 feet from the southern end of the Eastern Wall. The Herodian stones comprising the upper half of the wall are projecting slightly out from the wall. The further up the wall you look, the further the stones project outward. This projection formed the base of a Temple watch tower. In all likelihood, such towers were located in all four corners of the Temple Mount.

In the late nineteenth century, the English archaeologist Charles Warren sank a mine shaft near the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount. His objective was to determine how far down the wall went before it hit bedrock. To his amazement, the shaft went down 80 feet before he reached solid rock and the base of the wall. The total height of the wall at that point was close to 160 feet, almost 16 stories high.

Warren also made the amazing discovery that the foundation stones contained Phoenician lettering. Some letters were carved into the stone; others were painted in red ink. These letters were marks made at the quarry to later identify the stones in order to set them in their correct positions for the foundation of the great wall.21

The columns on top of the Temple Mount consisted of sections, called drums, that fit one on top of the other (Plate #13). The drums had to be arranged in a specific sequence. To ensure the proper arrangement, the bottoms of the drums were marked at the quarry with letters. All work carried out on top of the Temple Mount was performed by Kohanim who were unfamiliar with Phoenician lettering; therefore, the marks on the bottoms of the drums were made in Hebrew. Since the marks of these foundation stones were Phoenician, these stones probably were set into place by non-Jews who were more familiar with the foreign script.

(Plate #10) Inside the Mercy Gate. The column to the rear probably dates back to the Second Beit Hamikdash. The column in the foreground dates to the fourth century Byzantine era.

Warren’s 80-foot-deep shaft remained exposed for about 100 years. A few years ago, the municipal officials considered the open pit to be a safety hazard and had it filled in. A bulldozer dug up earth from the surrounding area and dumped it into the shaft.

In any archaeological site, the further down one digs, the more ancient the relics that are exposed. But here, the order became reversed. The bulldozer carted upper layers of earth and deposited it into the bottom of the pit. It then returned to dig up the next layer and deposit it in the pit. When the task was completed, the bottom layer of the filled-in Warren’s Shaft contained the remains of 20th-century pottery, Coke bottles and discarded newspapers, which I suspect will certainly puzzle archaeologists of future generations. Imagine finding a copy of Ma’ariv in the dining room of a fourth-century Byzantine house! But, more importantly, the upper layer of fill in Warren’s shaft contained the remains of very ancient relics, a veritable treasure trove which I just had to examine.

Probing through the fill, I found two types of Herodian building stones. Both types had the carved margins typical of the Herodian Temple stones.22 However, one type of stone had a perfectly smooth center, the other type had a weave-like design carved onto the stone. The difference can be explained according to halachah. The rulingis that building stones that were used in the innermost courtyard (azarah) had to be perfectly smooth.23 No nicks or cracks should be detected by running the thumbnail across the surface. Stones that were used in construction for the outer courtyards did not have this halachic restriction (Plates #6a, 6b).

The Talmud tells us that the flooring was fashioned of marble tiles.24 There were three colors of tiles: white, brown, and bluish-purple. In the fill, I found two fragments of marble tiles. One fragment was brown, the other fragment was bluish-purple (Plate #8). I also found a stone oil lamp (Plate #7). Most oil lamps found in the Holy Land were made from clay. But baked clay utensils are susceptible to becoming defiled (tumah), while stone vessels cannot. It is therefore understandable that an oil lamp found in the vicinity of the Temple would be fashioned out of stone.

(Plate #11) The back of the Mercy Gate. A Corinthian column can be discerned between the two arches in this 110 year old photograph.

And now for the riddle alluded to in the title of this article. Quoted earlier was the mishnah which stated that above the Shushan Gateway was a depiction of the Persian capital, Shushan. I have often wondered how the Temple builders depicted Shushan. Did the city have a recognizable skyline, like New York, Chicago, or St. Louis? Did Shushan have some remarkable structure, like the Empire State building or the Acropolis, that symbolized the capital of the Persian Empire? Probably not. If so, how was Shushan depicted above the Eastern Gateway?

Built onto the top of the facade of the Mercy Gate is a little-noticed capital of a Corinthian column (Plate #9). In classical Greek and Roman architecture, there are three distinct styles: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. A capital of a column is the decorative stone on top of a column. Corinthian capitals are the most ornate of the three styles and usually consist of three tiers of acanthus leaves. For an example of typical Corinthian columns and capitals, we will take a look at the inside of the Mercy Gate (Plate #10). The capitals, as well as the columns themselves, are quite possibly remnants of the Second Temple.

The Jewish historian of the late Second Temple Era, Josephus Flavius, tells us that the architectural style of the Herodian Second Temple was Corinthian.25 Classical rabbinic literature translates the word “Corinthian” into Hebrew as shushan, meaning lily-like or floral.26 King Solomon also used floral capitals for his First Temple columns and the Hebrew term used in Tanach to describe them is also the word shushan.27 Corinthian, or Shushan, capitals were also common in ancient temples and palaces.28

In many languages, the same word is employed to denote the capital of a column and the capital city of a country. Perhaps, above the ancient Eastern Gateway was a large Corinthian/Shushan (i.e. floral) capital symbolizing Shushan, the capital city. In other words, there was no carving or engraving depicting the buildings of Shushan; rather, an architectural play on words represented the Persian capital.

A further connection between Corinthian architecture and the Shushan Gateway can be made by the ornate design-work that remains on the structure. A more complete version still remains on the back doorway of the building (Plate #11). This design is certainly Corinthian in style. Some archaeologists, such as W. Harold Mare, believe that this design-work is from the Second Temple Era.

The small Corinthian capital that rests atop the Mercy Gate today, conceivably a relic of a Second Temple column, might be an architectural memory of ages past when a gigantic Shushan capital rested there.

In ages past, the ancient marble capital served to remind us of the place from which we came. Today it serves to remind us of the day when the Prophet Elijah will herald the Messianic Era and of the place to which we shall return. May it occur speedily in our days.

Rabbi Reznick is a maggid shiur in the Beit Midrash of Shaarei Torah of Rockland. He is the author of The Holy Temple Revisited, Woe Jerusalem, A Time to Weep and The Mystery of Bar Kokhba.

This article first appeared in the Summer 1996 issue of Jewish Action.

Notes

1. Rashi Ezra 1:1, Toldot Am Olam vol.I, p. 329.

2. Midot 1:3.

3. Tiferet Yisrael Kelim 17, note 67.

4. Sefer HaYuchsin 61a.

5. Menochot 98a.

6. Ezrat Kohanim vol. I, p. 105, para. 10.

7. See Menochot ibid. and Kelim 17:9 and commentaries ad loc.

8. Baba Metzia 114a & b.

9. “States” is a term used by sophisticated travelers, who have been abroad at least once. It usually is used by natives of Brooklyn, but it can heard in most Jewish sections of New York State.

10. See Jewish Action Summer 5755/1995, “The Forgotten Wall,” for a detailed description of this gateway and the entire expanse of the Southern Wall.

11. See Jewish Action Winter 1991/1992 for a discussion based on archaeological evidence as to the length of a cubit in my article concerning the Bar Kokhba Temple.

12. Sofrim 19:12.

13. Kaftor Voferach, chap. 6.

14. See Jewish Action Summer 5755/1995, “The Forgotten Wall.”

15. ibid.

16. Baba Batra 3b.

17. Yossiphon chap. 55.

18. Josephus, Wars of the Jews Book I, chapter 21 & Book V, chapter 5.

19. See Jewish Action Summer 5755/1995 for a description and photographs of the “stables.”

20. See Jewish Action Winter 5753/1992-3, “A Private Tour of the Western Wall,” for a description of Robinson’s Arch.

21. See The Holy Temple Revisited, published by Jason Aronson Inc., p. 62 for a picture and a discussion of possibly dating the lettering.

22. See Jewish Action Winter 5753/1992-3.

23. Rambam Beit Habechirah 1:15.

24. Baba Batra 4a and Rashi ad loc.

25. Wars of the Jews Book V, chap. 5.

26. Such as Ezrat Kohanim.

27. Kings I 17:19.

28. Beneath the southern section of Har Habayit is a 300-foot-long tunnel with domes supported by columns. See Note #13. One of the columns has a very primitive Corinthian/Shushan capital, possibly a remnant of King Solomon’s First Temple.