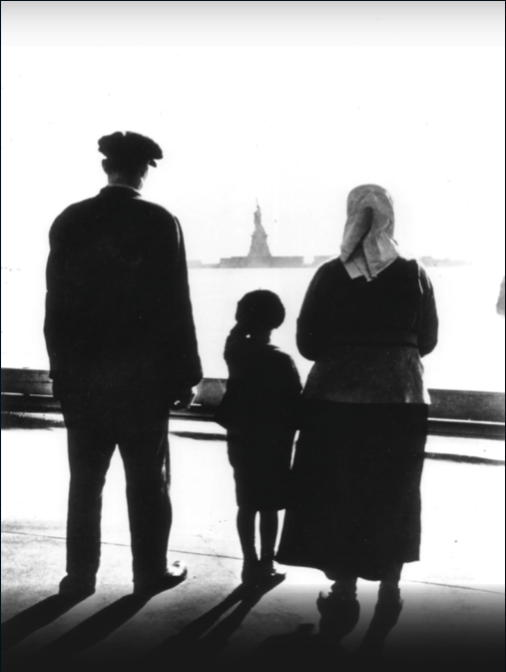

An immigrant family in the 1930s on Ellis Island looking across the New York Harbor at the Statue of Liberty. Photo: FPG/Getty Images

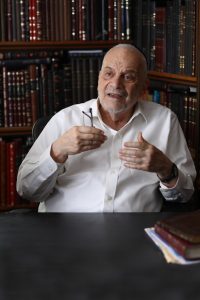

Jewish Action Editor-in-Chief Nechama Carmel spoke with famed lecturer, author and historian Rabbi Berel Wein about how resilience has shaped the Jewish historical experience, specifically the American Orthodox community in the postwar era.

Nechama Carmel: With the ongoing coronavirus challenging us in so many different ways, it would be interesting to know how you, as one with a deep understanding of Jewish history, define resilience.

Rabbi Berel Wein: Resilience is the ability to accept defeat and tragedy, to see beyond the present and to persevere with emunah, belief, and a vision for the future.

We find this concept clearly in Tanach. All the books of the prophets combine tragic and dire predictions with great hope and an almost utopian vision for the world and for the Jewish people. So much pain is expressed in the prophecies of Yirmiyahu, Yeshayahu, Yechezkel and the twelve nevi’im of Trei Asar; yet they always end on a note of hope, with the idea that the Jewish people will prevail.

In order to be resilient, you must believe in Jewish eternity. You must be able to believe in a world you haven’t seen. You must believe that things will get better, if not for me then for my grandchildren. This is a very difficult level of faith to achieve, because we tend to live in the present, and we may never, on an individual level, live to see a positive outcome.

The Gemara cites many examples of this kind of broad vision. One of the best illustrations is the story of a man who was planting a sequoia tree. People told him, “It takes seventy years to grow. You are an old man. You’ll never live to see it!” “That’s true,” he replied, “but somebody planted a sequoia for me, so I’m planting one for the future.”

When you have that mindset, you are living not only in the present but with an awareness of the entire span of Jewish history.

NC: In your view, what has given the Jewish people the ability to persevere and to focus on the future? From where do we draw the strength to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps time after time? Is it our faith?

RW: It’s always a question of faith. Emunah is difficult to define. Our children have to be raised with it innately; you can’t teach it with a curriculum. Children learn from the way their parents react to difficulties and disappointments. A child who’s never dealt with disappointment won’t do very well in this world.

NC: Starting over. Rebuilding. These are recurring themes in Jewish history. Can you share examples of leaders who helped the Jewish people bounce back after trauma?

RW: The greatest example of resilience in Jewish history, which is perhaps underappreciated, is the generation of the Shoah and the one right after it. Across the gamut, those leaders—the great Chassidic rebbes including the Satmar Rebbe and the Klausenberger Rebbe, as well as roshei yeshivah such as Rabbi Aharon Kotler and Rabbi Dr. Samuel Belkin, and even secular Jewish leaders such as David Ben-Gurion—exhibited extraordinary resilience.

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, when a third of our nation had been murdered, it seemed like Jews were finished. Certainly, Orthodox Jewish life was gone to a great extent, and the Conservative and Reform movements appeared to be the only Jewish movements that would thrive in America. Many Jews were driving to shul on Shabbos. Organized Jewry at the time opposed the day school movement, charging it with being “un-American” and fostering “dual loyalty.” Yet visionaries like Dr. Joseph Kaminetsky, the first director of Torah Umesorah-The National Society of Hebrew Day Schools, persevered, and succeeded in changing the face of American Orthodoxy.

Resilience is the ability to accept defeat and tragedy, to see beyond the present and to persevere with emunah, belief and a vision for the future.

And it wasn’t just the leaders. In every town in America that has a Jewish day school today, there were “ordinary” Jews who built and supported it in some way. I’m inspired by that because I am a member of that generation. There was a Jew in Chicago who paid my yeshivah tuition for twelve years because my parents couldn’t afford it.

NC: That’s extraordinary. Can you elaborate on one or two personalities who were responsible for leading the renaissance of Torah Jewry after the Holocaust?

Rav Aharon Kotler (bottom left at the bimah) giving a shiur in a shul in the New York area. Courtesy of BMG Archives

RW: Rav Aharon Kotler, who arrived in the United States in 1941, had a vision: to rebuild on these shores what Hitler had destroyed. He felt there needed to be a core group of individuals devoted to intense Torah study almost to the exclusion of anything else, and that this would enable the Jewish people to survive. It was not meant to be a broad movement; he did not believe all of American Jewry should be learning in kollel. Rav Aharon began with a mere twenty-seven students in a ramshackle hotel in Lakewood, New Jersey. When he passed away in 1962, he had 250 students. He never dreamed that one day there would be 10,000 students in Beth Medrash Govoha (BMG).

What made him so successful? The innate love of Torah within the Jewish people was awakened by the European-born rebbeim in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, and their students were inspired to devote their lives to Torah. I’m not demeaning American-born or Israeli-born rebbeim, but the rebbeim who came from Europe were different. They were people with low material expectations who were hardened by life and who saw Torah learning as a central tenet to which everything else was subservient.

NC: In its early years, when BMG was still relatively small, what kind of impact did it have on the rest of the Orthodox world?

RW: Many of Rav Aharon’s students went into chinuch. As a result, his philosophy and worldview eventually became very influential—though not necessarily dominant—in the Orthodox world. BMG set a high standard that had a trickle-down effect. Over the years, I had many discussions with Rav Joseph Ber Soloveitchik. In the seventies, he told me, “The talmidim I have now are much greater than those I’ve ever had in the past.” He attributed this to Rav Aharon Kotler.

Ultimately, Rav Aharon’s students opened day schools, yeshivos and kollelim around the world. Looking back, the impact of Rav Aharon is inestimable.

NC: Who else played a major role in building Orthodoxy in the post-Holocaust era?

Dr. Samuel Belkin (left) with Albert Einstein (center) at a press conference regarding Albert Einstein School of Medicine, March 15, 1953. Courtesy of Yeshiva University Archives

RW: One individual I feel never got his due is Dr. Samuel Belkin, the second president of Yeshiva College (now Yeshiva University). To me, he is one of the unsung heroes who built Torah Judaism in America.

A talmid of the Chofetz Chaim in Radin, Dr. Belkin came to the United States in the 1930s. At the time, American Orthodoxy “imported” its rabbanim and talmidei chachamim from Europe; they were not homegrown. After the Holocaust, that was no longer possible and Dr. Belkin realized something had to be done to strengthen American Orthodoxy or it would succumb to the other more powerful movements.

A man of great vision, Dr. Belkin recognized an opportunity in America that not many others did: back in the forties and fifties, although America was tolerant of Jews, quotas made it very difficult for a Jew to get into medical school.

In the early 1950s, when I was in yeshivah, there were three young men who wanted to go to medical school. Because of the difficulties with college acceptance, the Jewish doctors in Chicago established their own medical school. These young men walked to the school every Shabbos, and had someone take notes for them. It was almost impossible to be a shomer Shabbos medical student in those days. Certainly no one ever imagined there would one day be a shomer Shabbos residency training program.

Dr. Belkin foresaw that America would eventually recognize the right of Jews to be Sabbath-observant. He was committed to the creation of schools to train professional laymen dedicated to the ideals of Torah Umadda. He believed that American Orthodoxy needed university-educated rabbis and professionals who were fully observant but would be recognized in the general world as well. I would venture to say that he felt that without the balance he brought to the Orthodox Jewish community, Rav Kotler would not be successful either; there had to be Orthodox Jews who could financially support Rav Kotler’s vision.

Dr. Belkin dreamed big and he built the university as well as the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. And because of Einstein’s lead, today there are shomer Shabbos residency programs all over the country. But essentially Dr. Belkin was an ilui and a rosh yeshivah who continued to give his shiur.

NC: These are examples of leaders who, with remarkable courage and tenacity, set out to rebuild Judaism. But there were so many among the “hamon am,” the average men and women of that generation, who exhibited remarkable strength in the aftermath of catastrophic loss. I myself have grandparents who came to these shores as penniless survivors and managed to rebuild their lives. They worked hard, succeeded in restoring themselves financially, and built families, creating generations of Torah Jews. How did they do this?

RW: European Jews were a different brand, a completely different brand. Their stoicism and their low expectations rendered them resilient. My parents, who were European-born, never owned their own home; they did not even own an automobile. We rarely ate chicken for dinner. But we never felt deprived.

Today we have enormous expectations and this contributes to much of our unhappiness. High expectations, also play a part in many issues, such as the high divorce rate in our community and the shidduch crisis. As a society, we foster the illusion that perfection—the perfect yeshivah bachur or the perfect girl—is attainable. The European Jew was realistic and had realistic expectations. His realism was derived from the type of life Jews had lived for the last eight hundred or more years. (Anyone who portrays shtetl life as idyllic is telling a falsehood.)

The key to a more blissful life, if such a thing is ever possible, is having lowered [material] expectations; albeit, we should have great expectations spiritually.

When you study Gemara, you realize that none of the Tana’im or Amoraim lived in an ivory tower. Those who were wealthy had other challenges. Some had children who strayed from the path of their teachers. The Gemara is not hagiographic; it is very forthright. Knowing what happened in the past provides the realism necessary for the present.

The coronavirus provided us with a harsh dose of realism. Corona taught us that you can have the most successful business in the world and it can be destroyed in three months. You could have a great stock portfolio, and a minute later it could be gone. That is a real life lesson. Whether or not people will internalize this message of realism, I don’t know.

NC: So historically speaking, the hardships of life have made Jews resilient. What does that mean for us nowadays? On the whole, we Americans are a pampered generation. How can we build our internal resources so we can be mentally and emotionally stronger?

RW: The key to a more blissful life, if such a thing is ever possible, is having lowered [material] expectations; albeit, we should have great expectations spiritually.

Some of my grandsons have completed Shas a number of times. I have not, but they have. They are willing to live in small apartments with large families and they’re happy. In fact, they are just as happy as people who are trying to sustain a sixteen-room house and living paycheck to paycheck to do it.

My rebbe used to say Mashiach can’t come now because we’ve placed too big a load on him; he can’t fulfill our expectations. The Rambam describes a very minimal Messianic expectation: the elimination of shibud malchiyos, that is, in Messianic times Klal Yisrael will no longer be subservient to the nations of the world.

Lowering our material expectations reduces frustration, sadness and depression, which in turn makes us much more resilient. One who was able to take his entire family every year to a Pesach hotel in Hawaii and could not do so during the coronavirus might have viewed it as a sad Pesach. However, one who has no expectations for Pesach except to fulfill the mitzvos of eating matzah and drinking the four cups of wine will never feel disappointed.

Today we have enormous expectations . . . The European Jew was realistic and had realistic expectations.

In Parashas Bechukosai and again in Parashas Ki Savo, the Torah predicts that God will send us into exile. One of the cardinal questions asked is: Why did God send the Jewish nation into exile? The answer is because without the exile we would not have survived as a nation. Not only did we endure the loss of our land, we endured the travails of living under foreign rule and were subjected to intense suffering over the centuries. Exile hardened us and gave us the wherewithal to survive as an eternal nation.

On an individual level, we should be satisfied with what Hashem gives us. We should envision a brighter future. We should support the Land of Israel and the people of Israel. And we should view ourselves as part of the great historic process called “Klal Yisrael.”

More in This Section:

Jewish Resilience: Holding Strong in a Time of Crisis by Jacob J. Schacter

Crusades and Crisis by Sholom Licht

Plagues and Perseverance by Faigy Grunfeld

Finding Light in the Darkness: The Art of Jewish Humor by Steve Lipman

The Ability to Bounce Back: The Psychology of Resilience by Shana Yocheved Schacter