Rabbi Leibel Reznick Asks: When Was the Second Temple Really Destroyed?

PART I

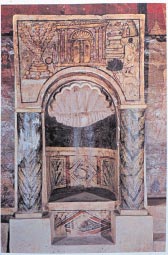

The year is 255 ce. The place is Dura-Europos, a Roman garrison town on the western bank of the Euphrates. The elderly Reb Shmuel HaKohen looks around his synagogue. The morning service is about to end. He knows that this is the last time his prosperous community will be davening here. He stares at the synagogue walls—beautiful walls covered with warm-hued paintings. There is Abraham about to sacrifice Isaac, Jacob dreaming of a ladder that reaches the heavens, the infant Moses being rescued by Pharaoh’s daughter. Reb Shmuel studies the images of Moses standing before the burning bush, leading the Children of Israel out of Egypt and parting the Red Sea. He glances at King Saul, King David, the prophets Elijah and Ezekiel. To the left of the holy ark is Mordechai the Jew riding the royal stallion, being led by the humiliated Haman. Above the ark is a depiction of the Holy Temple and the sacred menorah. (See plates 1 and 1a.)

To the right of the ark are the four steps that lead to Reb Shmuel’s seat on the western wall.1 He will never sit there again. He gives one last look upward to the ceiling with hundreds of beautifully decorated tiles and large ornate wooden beams. A knock at the door disturbs his reverie. The Roman soldiers have arrived. They are carrying shovels, and behind them are wagons loaded with dirt and rocks, which will fill the synagogue. Reb Shmuel gives his blessings to the Roman soldiers and wishes them success.

The 250 Jewish families of Dura-Europos always had a very good relationship with the local Roman population. They were now facing a common enemy: the Persians were planning an attack against the town. Because the synagogue was next to the western city wall, which was the most vulnerable part of the city, it had to be reinforced. And so the synagogue, along with all the other buildings that abutted the wall, was to be filled with rocky soil in order to strengthen the wall.

Unfortunately, the plan was not successful. The city was overrun by the Sassanian Persians. We do not know the fate of the Jews of Dura-Europos. Their synagogue remained buried under the rocky dirt for 1,700 years. It was not rediscovered until the 1930s during an archaeological excavation under the auspices of Yale University.

PART II

“Whoever had not seen the Temple of Herod [the Second Beit Hamikdash, as rebuilt by King Herod] had not seen a beautiful building in all his days” (Baba Batra 4a).

The Second Beit Hamikdash was one of the most magnificent structures ever erected by man. Its great courtyards and huge buildings were admired by Jews and non-Jews alike. Its splendid Romanesque architecture and display of gold, silver and brass ornamentation staggered the imagination.2 The primary building material was stone. Great limestone blocks—some weighing several hundred tons—were hewed from local quarries, finely finished and hauled to the Temple Mount. The use of wood was restricted because of halachic constraints. “Thou shall not plant for yourself an (idolatrous) Asherah (tree), any wood, near the Altar….” (Deuteronomy 16:21) The sages taught that the phrase “any wood” restricted the use of wood as a building material within the Temple courtyard.3

We do find two references to wood being used as a building material. One reference is with regards to the great hall (ulam) that stood in front of the Heichal (the main Sanctuary, housing the Holies and Holy of Holies). “Beams of cedar wood were set in between the (one-hundred-cubit high) wall of the Heichal and the (one-hundred-cubit high) wall of the ulam so (that the walls) would not lean (and collapse) (Middot 3:8).” The commentary Tiferet Yisrael (1:6) suggests that the beams were not cemented into the walls and therefore did not violate the prohibition of using wood as a building material.

The second reference to wood being used as a building material is with regards to the ceilings of the Holies, Holy of Holies and the upper chamber of the Heichal. All of these rooms had ceilings that were forty cubits (sixty to eighty feet) above the floor level and were five cubits (seven-and-a-half to ten feet) thick. The first cubit of thickness consisted of decorative plaster or, according to some, gold-plated mahogany. The second and third cubits were thick wooden beams. The fourth consisted of thinner wooden beams, and the fifth of mortar and tiles. (Middot 4:7) Tiferet Yisrael suggests that since the wood used in the ceiling was not exposed, it did not violate the prohibition of “any wood near the Altar.” Only wood that was exposed and projected into the air would resemble a tree and therefore be forbidden. (Though there are five or six other instances where wood is mentioned as a material used in the Temple, in all of those instances the wood was not used in a structural context.)

Since stone was the primary building material, how did the Roman invaders burn down the Second Temple?

The Temple was set ablaze on the ninth day of Av, towards sunset. The fire continued to rage through the night and into the following day.4 Since stone was the primary building material, how did the Roman invaders burn down the Second Temple? Flammable wood was hardly used, and in those cases where it was, such as in the ceilings, it was quite high off the ground—between sixty to eighty feet—and not exposed. What caused the Temple to burn?

Surrounding the Temple courtyards inside and out were great colonnades.5 These were ornate roofs that were supported by large marble columns. The first century Jewish historian, Josephus Flavius, who served as a Temple priest, gives us a firsthand description of the colonnade that lined the southern wall of the Temple mount:6

The colonnade that was southward had gates in its middle and three aisles which went from the eastern [Temple] wall above the valley [of Kidron] to the western [Temple] wall [approximately 1,000 feet]. This colonnade deserves to be mentioned more than any other under the sun. One standing on the roof of the colonnade could not see the bottom of the (Kidron) valley for the roof was so high and the valley was so deep. The view would make one faint. The [three aisles] were marked by four parallel rows of columns. The fourth row was set into the [southern] wall. The thickness of each pillar was such that three men with their arms extended and joined hands were required [to surround a single column]. The height of each column was twenty-seven feet with a double base.

The number of columns was one hundred and sixty-two. Their capitals were sculptured after the Corinthian order [floral design]. [See plate 5.] The grandeur of the whole [structure] caused wonder [in the eye of the beholder]. These four rows of columns marked the three aisles. The two [outer] aisles were built in a similar proportion. The width of each aisle was thirty feet, the length was a furlong [about 1,000 feet], and the height fifty feet. But the middle aisle was one and a half times as wide [forty-five feet] and twice as high [one-hundred feet]. The roof supported by the columns of the middle aisle was twice as high as the roofs supported by the columns of the outer aisles. The roofs were adorned with deep sculptures in wood with many sorts of designs.7

It took Herod one-and-a-half years to rebuild the main structures of the Second Temple; however, it took him eight years to complete the construction of the colonnades. Such was their magnificence!8

The roofs of the colonnades were constructed of wood9 as mentioned by Josephus. In addition, Josephus, who witnessed the actual destruction of the Temple, tells us that it was these colonnades that were set afire by the Romans, and it was the colonnades that accounted for the major damage.10 It is my contention that after the fire had burned itself out, the basic structure of the Temple remained intact and, though severely damaged by the heat of the surrounding fire and tainted by the billowing smoke, it was still standing and readily recognizable.

Rebbe Elazer says: “One who sees the Temple in ruins should say ‘Our Holy Temple, our glory, which our fathers had praised, was burned in fire and all our delights have become a ruin.’ He should then rend his garments.”11

Rebbe Elazer lived one generation after the destruction of the Temple, yet he referred to the ruins of the Temple. It seems that in his time there were still discernable remains of the Temple, unlike today when no visible ruins can be seen.

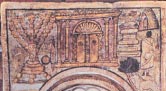

The Bar Kochba revolt took place during the lifetime of Rebbe Elazar, approximately fifty to sixty years after the destruction. Bar Kochba minted coins depicting the facade of the Heichal. (See plate 2.) Coins depicting temples were common in the Roman era, but only extant temples were depicted. It was pointless to depict a building that was no longer standing since the image would be meaningless to the one viewing it. This indicates to me that the Temple ruins were still standing in the time of Bar Kochba.12

There is much evidence that the Temple ruins were still standing at around 135 ce, when the Bar Kochba revolt was quashed by the Roman emperor, Hadrian. One medrash states: When Hadrian entered the Holy of Holies, he showed great arrogance and blasphemed God.13 Furthermore, the Byzantine historian Chronicum Paschale14 confirmed that the Temple still stood in the time of Hadrian.

Rambam writes: “Five things occurred on the Ninth of Av…On that day, which was destined for tragedy, the evil (governor) Tinnius Rufus plowed up the Temple Sanctuary and its environs.”15

Tinnius Rufus was the governor during the rule of Hadrian. The fact that he plowed up the Sanctuary indicates that it was still standing at that time. It is well known to students of Roman history that the expression “to plow up” an area is not to be taken literally. It refers to a ceremony that was performed after a conquest. A team of oxen was harnessed and a furrow was dug around a captured city to symbolize its capture. There are Roman coins depicting this ceremony. (See plate 3.)

Hadrian did not dismantle the Temple ruins but converted the structure into a pagan Temple. This was done to humiliate the Jews rather than because of any religious conviction on the part of the emperor.16

How long did the Temple stand? We mentioned earlier two depictions of the Temple: one on the Bar Kochba coins and the other among the wall paintings of the Dura-Europos synagogue. The resemblance between the two images is quite remarkable. Both show the same doorway, a curved arch with double doors. Both show four great columns in front of the doorway, supporting a roof. Both seem to show scalloped edging on the top of the roof. From where did the Dura-Europos builders (circa 250 ce) get this image? If it was copied from the Bar Kochba coins, then the images should be exactly the same. However, there are some differences. The Bar Kochba coins show columns adorned with the simple Doric-style capitals (see plate 4), whereas the wall painting depicts the ornate Corinthian-style capitals (see plate 5). The wall painting also shows two smaller columns flanking the doorway. The painting is a more accurate depiction since Josephus already told us that the columns of the Temple were of the Corinthian order. Also, there were two columns, called Yachin and Boaz,17 flanking the doorway. The small image on the coin could not show details such as the Corinthian capitals or the Yachin and Boaz. Thus, it would seem that the painters of the Dura-Europos walls were not inspired by the coin but by the actual remains of the Temple in Jerusalem.

It therefore seems that the Temple was still extant in the year 250 ce. How much longer did it remain? An indication that it no longer stood by the mid-fourth century can be found in a letter written by the Byzantine emperor Julian who believed in tolerance and freedom of religion. During a campaign against his Persian enemies, Julian wrote to his Jewish constituents that he was granting them permission to clear the Temple Mount of debris and rebuild their Temple. Unfortunately, Julian was killed during the campaign, but his letter indicates that the Temple was no longer standing.

It would appear that the Temple was demolished sometime between 250 ce, when the painting was commissioned, and 360 ce, when Julian composed his letter. Logic would place the demolition at around the year 330 ce, during the reign of Constantine. For the first time the Eastern Roman Empire, now called Byzantium, was Christian. Constantine’s mother, Helena, was a devout believer in Christianity. She journeyed to Jerusalem and began changing the former Roman pagan city into a Christian holy site. Devout Christians would have no use for Hadrian’s pagan temple atop the Temple Mount. They would have no use for the surviving remains of the Temple of the Jews. For the first time in 680 years, the Temple Mount was bare.

We had always thought that after the Roman destruction in 70 ce, there were no visible and identifiable remains of the Beit Hamikdash. We now have reason to believe that the Temple remained fairly intact for another 260 years. May we be worthy of the kindness of the One Above and merit to see the rebuilding of our Temple, heralding the epoch of brotherhood and universal peace.

Oh yes, I almost forgot something. There is one other building depicted on the Dura-Europos Synagogue walls. Its identity remains a mystery. (See plate 6.) Any ideas?

Rabbi Reznick is the author of The Holy Temple Revisited (Jason Aaronson, 1990); A Time to Weep (CIS, 1992) and The Mystery of Bar Kokhba (Jason Aaronson, 1996).

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Jewish Action.

Notes

1. Jerusalem is west of Dura-Europos.

2. When the Temple riches were plundered and released into the open market, the price of gold plunged fifty percent.

3. Sifri, Tamid 28b and Rabbeinu Gershom ad loc.

4. See Ta’anit 29a.

5. These are also commonly referred to as cloisters, porticos, excedras and stoas.

6. Antiquities, Book XV, chap. 11, par. 5. See also Wars, Book V, chap. 5 par. 2 for a further description of the colonnade. The quoted remarks in this article taken from Josephus’s works are not direct quotes from any English translation of the original Greek but are an accurate paraphrasing to make it more intelligible.

7. The designs were geometric and floral patterns. No animal or human representations were depicted.

8. Antiquities, Book XV, chap.11, par. 5.

9. Also, Rabbeinu Gershom in Tamid 28b.

10. Antiquities, Book VII, chap. 10, par. 2; Wars of the Jews, Book VI, chap. 6.

11. Moed Katan 26a.

12. Readers of my books and other articles that appeared in Jewish Action are well aware of my theory that Bar Kochba restored the Temple during his reign in Jerusalem.

13. Shemot Rabbah 51:5.

14. Mystery of Bar Kokhba, p. 73.

15. Hilchot Ta’anit 5:3.

16. The dedicatory plaque of Hadrian’s temple can still be seen today, built into the southern Temple wall.

17. These two columns, mentioned with regards to the First Temple, were also in the Second Temple. See Ezras Cohanim 3:7.