By Joshua Berman

Tears to do not come easily on Tisha B’Av to all of us. Rabbi Joshua Berman explores the reason why.

Probably no holiday season on the Jewish calendar evokes as little emotion as the three weeks bracketed by the 17th of Tammuz and Tisha B’Av. Not out of irreverence, mind you. Each of us will steadfastly avoid the swimming pool the week before Tisha B’Av, and consume the requisite egg a la ash at the seudah mafseket. Yet for most of us, thoughts of the destruction of the Beit Hamikdash don’t really send us looking for a tissue to wipe away the tears, let alone sink us into deep depression. In fact, the whole season is, for most of us, pretty baffling. What’s all the fuss? Jewish life flourishes, our communal institutions are strong, Israel is a strong and growing state; the term churban seems out of place in our times.

Our inner conflict regarding the Temple and its destruction, however, runs deeper. We’re actually wary of the Temple. A “house” for God? Something doesn’t feel right inside. It sounds “pagan,” maybe even barbaric. Rebuild the Temple “speedily in our day”? That would mean blowing up the Dome of the Rock. Sounds fanatic.

And yet we know that we should want the Temple. After all, half of the 613 commandments depend on it. Without the Beit Hamikdash, the Torah becomes the three-and-a-half books of Moses. There is hardly a prayer that does not allude to it, from the Amidah to Birkat Hamazon. Something visceral inside us resonates at the very thought of the Kotel Hama’aravi.

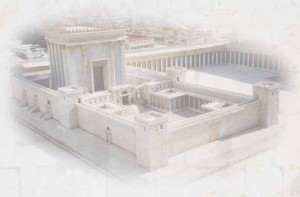

In this essay I would like to begin rebuilding the Temple’s image. In my recent book, The Temple: Its Symbolism and Meaning Then and Now, I try to show that the Temple cannot be studied in isolation. Rather, I claim that the it is the central institution of the Bible’s view of the Jewish world. It is the hub that links Shabbat, the land of Israel, kingship, our relationship to the non-Jewish world, Mount Sinai, education and justice.

The key to understanding the Temple is to explore its symbolism. The anthropologist Clifford Geertz claims that we utilize symbols as a vocabulary with which to grasp concepts and ideas that are too abstract for us to convey through words. Thus, as an example, we relate to a departed soul through the symbolic agency of the flame of a yahrzeit candle.

Now, the concept that God somehow “dwells” with the Jewish people is certainly an abstract one, one that is hard to grasp literally. To explore the Temple’s symbolism and how it helps us integrate and comprehend the meaning of the statement “God dwells with us,” we will examine one of the Temple’s many names. The development that I would like to present is that of Rabbi Yoel Bin-Nun of the Herzog College at Yeshivat Har Etzion.

Geulah needs to be seen as a process, with many small steps along the way.

An entity can have many names, each different, where each name represents another facet of that entity. Take for example, yours truly. My students call me Rabbi Berman; my three-year-old calls me Abba-leh. My wife also has a name for me, but that’s not for here. Each of these names reflects a different facet of my identity. It’s the same with the Temple. Chazal called it Beit Habechirah; the Tanach refers to it by many names: Mishkan, Mikdash, Beit Hashem. For our purposes, I would like to explore one of these names — the name that appears in the book of Devarim. (Deuteronomy) some twenty times: hamakom asher yivchar Hashem leshaken shemo sham — literally, “the place that God will choose to establish His name there.”

Just what does that mean, the place that God will choose to establish “His name there?” We could make more sense out of the phrase to establish Himself there, or to establish His presence there; but what is meant by establishing His name there? Certainly it is a command to do more than chisel Y-H-V-H on the walls.

The Hebrew word shem functions in precisely the same double manner as the English word name. A name is a label that we attach to an entity. Yet the word name can also mean reputation, as in the phrase “he is worthy of his family’s name.” In Hebrew as well, shem means name in the sense of a label, but it also implies reputation, as in the verse “tov shem mi’shemen tov” — “A good name is better than good oils.”

The Temple, says the Torah, is to be a place that God chooses to establish His shem — His name, His reputation. When miracles abound, as in the time of the Exodus, God’s acclaim in the world is achieved through supernatural intervention. Yet once the Jewish people enter the land of Israel, miracles nearly cease. From this point on, His acclaim in the world as sovereign is directly linked to Israel’s actions and fortunes. During the period of the Judges, therefore, when Israel was weak, it was hardly a vehicle for the spread of God’s acclaim in the world.

To understand the conditions that were necessary for King Solomon to build the first Temple, we really need to ask under what conditions would a nation — any nation — command broad respect? Today we would say that a great country is one that possesses political stability at home and is at peace with its neighbors. It should possess a strong economy and should be home to a culture that boasts strong virtues.

These are precisely the attributes that the Book of Kings depicts in great detail in the chapters leading up to the Temple’s construction. Solomon was the first leader of Israel to establish a pact with a neighboring power. His empire enjoyed unprecedented security and wealth. Prior to Solomon, no ruler of Israel had ever inherited his position. His ascension to the throne, inaugurating the Davidic dynasty, signified unparalleled domestic stability. Above all, Kings tells us that Solomon was recognized by the surrounding cultures as a master of wisdom in all realms, wisdom that led to the foundation of a society of justice and social welfare.

This is a profound redefinition of the Temple’s identity and purpose. The Temple, in this light, is not merely a place of worship and ritual, a religious center. Rather, the Temple becomes integrally related to the political, economic and social development of the society. Only when all of the societal pieces are in place does Israel earn the respect of other peoples. Only when Israel sanctifies God’s name in this fashion can a structure be built to symbolize His acclaim in the world, as the inspiration that allows Israel to achieve her greatness.

This conception of the Temple can help us grasp the times in which we live. As we approach the three weeks, the term churban (destruction) comes to the fore. In our time, churban seems strangely out of place. Is modern day Jerusalem churban? One cannot even buy a plot of land upon which to build. Indeed, some contemporary poskim have amended the prayer Nachem, said on Tisha B’Av afternoon, to reflect Israel’s recent fortunes. Yet churban, when understood in light of the ideas expressed earlier, remains a relevant concept.

When conditions do not allow us to rebuild the Temple, we are not merely mourning the absence of a shrine or of the capacity to bring sacrifices. It is a potent sign from above that God does not desire a house to be built at this point in time to symbolize His affiliation with the Jewish people. It is a slap in the face to us as a collective people. The fact of churban highlights to us that we have yet to create a society that is truly a sanctification of God’s name — His acclaim in the world. Until those conditions come about, God, as it were, holds back, and refuses to permit the erection of a symbol of his affinity with us.

Nevertheless, the times we live in are also times in which we actively rebuild the Temple; for the erection of the Temple begins with the construction of a model society. Some Jews regard the process of geulah as an all or nothing proposition. Either the Temple stands or it does not. Either the Davidic line reigns over Israel, or it does not. Either the law of the land is halachah, or it is not. In the absence of any of the above, the theory goes, Israel is in a full state of churban.

Yet, from a religious Zionist perspective, geulah, and with it the foundation for a third Temple, needs to be seen as a process, with many small steps along the way. There is meaning to a rebuilt Jerusalem even as the Temple remains unbuilt. There is theological significance in Israel’s surging economy, and there is meaning in the return of over 700,000 olim in the last seven years.

Many of us are deeply disturbed by the abandonment of Jewish values in Israeli society, and particularly in many government policies. Yet this should not keep us from recognizing the steps that have been taken to make Israel a more complete and perfect society. Any activity which builds Israel — religiously, politically, economically, or socially — is a step toward rebuilding the third Temple, for the Temple stands as a symbol of God’s acclaim in the world.

To mourn for the Temple is not to mourn for stones or even for the inability to offer sacrifices. To mourn for the Temple is to recognize the covenantal calling to create a perfect society, and to draw attention to the shortcomings of the Jewish world which is our own.

Rabbi Berman is a Bible professor at Bar Ilan University and is the author of The Temple: Its Symbolism and Meaning Then and Now (Jason Aronson, 1995).