By Yehuda Berenson

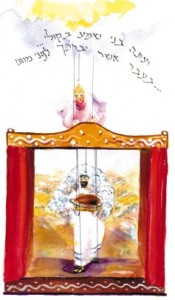

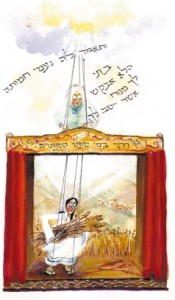

The puppets represent Ruth and Jacob performing on the stage of history. Ruth gathers the sheaves of wheat in Boaz’s field while Jacob—wearing the sheepskin—carries food for his father. Naomi directs Ruth, and Rebecca directs Jacob, each woman acting with the conviction that she is doing God’s will. In turn, both Naomi and Rebecca are puppets in the hands of God.

Illustrations by Caryl Herzfeld

In 1616, Rabbi Joel Sirkes1 (popularly known as the Bach)2, a noted rabbinical scholar who authored several works on Jewish law,3 published Meishiv Nefesh, his only opus on the Tanach.4 In this commentary on Megillat Ruth, the Bach uncovers a linkage between the Megillah and the story of Jacob’s acquisition of the blessing that his father, Isaac, had intended for the older brother, Esau.

Interestingly enough, this particular association of two Biblical episodes5 seems to have escaped the eye of the scholarly world. This is especially surprising in view of the fact that Bible scholars have written extensively on connections built into Megillat Ruth tying it to no less than three other stories in the book of Bereishit!6

But why should a writer want to establish links between two different stories? Scholars conclude that by linking scenes from books such as Esther or Ruth to episodes in Bereishit, each tale is enriched; ideas are shared, and common features are highlighted. This technique is highly advantageous when writing a short story—Megillat Ruth contains only eighty-five verses—because it is difficult to give themes and messages their full due when space is at a premium. Tying scenes from Megillat Ruth to Bereishit stories in particular was very desirable; Bereishit stories were imbibed by Israelites with their mother’s milk; they were known by heart, and therefore readers (and listeners) were easily able to spot expressions common to the two narratives.

The bonding of two Biblical sources required use of common words and phrases. Rabbi Sirkes noted that the term vayecherad (he was agitated) appears in both the Jacob-Esau episode and the Ruth narrative. This finding may have been the catalyst that sparked the revelation of the link between the two stories. Once a common key word is discovered, the search for other examples of shared language follows. The table below lists some of the expressions shared by Megillat Ruth and chapter 27 of Bereishit. (Note that the sources may occasionally differ in gender.)

BEREISHIT 27 RUTH

An older person is concerned for the family’s future:

| “…behold now, I am old” (2) | “…for I am too old to wed” (1:12) |

An older person is advising an offspring, or someone referred to as if he or she were an offspring:

| “…and now, my son” (8) | “…my daughter…and now” (3:1-2) |

The person who must act is hesitant, so he must be “commanded” to follow the instructions:

| “…give heed to what I am commanding you” (8) | “…and she did just as her mother-in-law had commanded” (3:6) |

The “planner” specifies clothing to be worn:

| “…Esau’s garments…and she put the skins of the young goats upon” (15-16) | “…and put on your (better) garments” (3:3) |

Conditions of “darkness” compel the person approached to ask the identity of the emissary:

| “…who are you, my son?” (18) | “…who are you?” (3:9) |

The person approached has been eating and drinking in the earlier part of the story:

| “…and he ate…and he drank” (25) | “…and he ate…and he drank” (3:7) |

The messenger fulfills his mission without being “caught”:

| “…before you (Esau) arrived” (33) | “…she arose before one man could recognize another (3:14) |

The person approached is agitated by what has occurred under cover of “darkness”:

| “…and Isaac trembled exceedingly” (33) | “…and the man trembled and turned himself” (3:8) |

Each emissary receives two blessings from the person approached:

| (27: 28-29), (28:1-4) | (2:12), (3:10) |

An unexpected complication is introduced by the words “and now” (va’atoh):

| (43) | (3:12) |

The original plan of action had also been introduced by the words “and now” (va’atoh):

| (8) | (3:2) |

There are additional words and phrases common to the two stories. We invite the reader to find them.

Along with the common phraseology, there are shared ideas and themes that deserve special attention. What are the similarities between Jacob (following his mother’s directions) seeking the blessing intended for his brother, Esau, and Ruth (following Naomi’s instructions) going to Boaz’s threshing floor in the middle of the night? Rabbi Sirkes makes the following points:7

1. Rebecca could have told Isaac about her preference for Jacob to succeed him as head of the house of the children of Abraham, just as Naomi could have chosen to confer with Boaz regarding the merits of his taking Ruth as his wife.

2. Both Rebecca and Naomi realize that the conventional path of persuasion through discussion is fraught with difficulties, and rule out this option. (Perhaps each woman concluded that once the man in question heard her out, were he to refuse or even remain unconvinced regarding the proposal, no recourse would be left, and the “candidate” proposed would be left floundering.) Thus, each tale deals with a socially unconventional scheme in order to promote a particular continuation of a family line.

3. In each case the older woman sends her “candidate” in complete faith that she is carrying out the will of the Almighty. The Bach maintains that each “planner” is endowed with prophetic vision and perceives herself to be an agent of the Lord doing her utmost—with complete trust in the Lord—to bring the plan to a successful outcome.

4. Naomi sees Ruth as a special descendant of Lot’s daughter who conceived a son, Moab, by way of her father. (Lot’s daughter did this out of a mistaken conviction that the destruction of Sodom threatened mankind’s continuation.) There was a mystical tradition among the Israelites that their spiritual redemption must await a return of an exceptional Moabite maiden to the folds of the house of Abraham. Naomi is convinced that her daughter-in-law is that extraordinary Moabite woman. She sends Ruth to Boaz at the threshing floor to reenact the attempt by her ancestress, Lot’s unnamed daughter, to provide for the continuation of civilization, although in a modified and more dignified fashion. In effect, Naomi is hoping that Boaz will realize that this woman, whom he has come to admire, is indeed that descendent of Lot who is destined to be the mother of Israelite royalty. (There seems to be an ongoing theme of redemption throughout the Megillah. We note that the Megillah deals with the redemption of Naomi’s plot of land as well as the redemption of Ruth from her widowed state. Professor Harold Fisch suggests that in carrying out this particular act in such a chaste manner, Ruth is redeeming her ancestress who lay with her intoxicated father in Bereshit 19. It is this act, in turn, that spurs Boaz to take Ruth as his wife and redeem her.)8

5. Both “planners” see the hour as especially ripe for execution of their own scheme. It is vital to take advantage of this particular moment, for once the opportunity is lost, another propitious time may not arise.

5. Both “planners” see the hour as especially ripe for execution of their own scheme. It is vital to take advantage of this particular moment, for once the opportunity is lost, another propitious time may not arise.

6. In both episodes, the older woman “planner” is assuming that the person being approached will not deal unfavorably with the “emissary”; surely he will take note of the careful planning involved and realize that the messenger is not acting independently, but is following the instructions of an older woman.

To the above similarities uncovered by the Bach, we add the following:

1. Each tale involves the displacement of someone with “first rights” (Esau on the one hand and the “other redeemer” on the other).

2. In both episodes, the emissary appears reluctant to go (Jacob is afraid of being recognized and disgraced, whereas Ruth appears to carry out her mother-in-law’s instructions out of allegiance rather than conviction).

3. In both stories, an older woman provides the emissary with specific directions.

4. In each tale, an unexpected factor causes a change of plans (Jacob ends up having to leave home; Ruth must wait to find out whether or not the “closer” redeemer will agree to assume responsibility for her).

Having noted the striking similarities between the two narratives, we are left to consider the following: why did Megillat Ruth intentionally draw language from Bereishit 27, thus establishing a connection between the two episodes? What was the author of Ruth attempting to gain from such a linkage? According to Rabbi Sirkes, the linkage aims to explain why the two people directing the emissaries are obliged to take unorthodox action to achieve a goal of paramount importance. The “planners” saw that a direct approach to the person in question (Isaac, Boaz) was likely to meet with resistance. They sensed that this was a special moment when history was in the making and must be effectively exploited. Each “planner” rose above the specifics of the situation and chose a perilous course of action that defied the ordinary norms of behavior. Their judgment of their particular emissary—each of whom was destined for greatness—instilled in the initiators full confidence in plans demanding behavior that would ordinarily be unacceptable. According to Rabbi Sirkes there are moments—such as when the person involved is extraordinary and the results of inaction may be disastrous—when extreme action bordering on the unacceptable is permissible.

Lest a reader, considering a moment to be a now-or-never situation, be tempted to emulate Rebecca and Naomi, overstepping the boundaries of accepted norms, let him be cautioned by the Bach’s qualification. Rebecca and Naomi knew with prophetic certainty that Jacob and Ruth were destined to be, respectively, a leader and a mother of royalty. The Bach does not give blanket approval for anyone lacking such divinely granted insight to employ questionable means in dealing with important issues.

Dr. Berenson has rabbinic ordination from Yeshiva University and a Ph.D. in mathematics from Columbia University. He has taught at several universities in the United States, Canada, Israel and Australia. He is retired and lives in Israel.

Notes

1. Adapted from author’s forthcoming book, Illuminating Ruth.

2. Rabbi Joel Sirkes (1561-1640) served as rabbi of several communities in Poland and Lithuania. The original family name was Yafeh. In the world of Jewish scholarship, he is always known as the Bach, an acronym of the title of his best-known work, Bayit Chadash.

3. The Bayit Chadash was Rabbi Sirkes’s commentary on the Arba’ah Turim (the Tur), Rabbi Jacob ben Asher’s four-part code of Jewish law that served as a springboard for Rabbi Joseph Caro’s renowned Shulchan Aruch. Rabbi Sirkes also wrote over 200 responsa. He is particularly well known for his commentaries and emendations to the texts of the Babylonian Talmud.

4. Meishiv Nefesh was first printed in Lublin, Poland; it was reprinted in Lvov in 1876, and reissued more recently in Brooklyn, New York, 1982(?).

5. The linking of two texts that use common phraseology and have shared themes in order to shed light on the characters in each story has come be called intertextuality or, alternatively, echo narrative technique. The intricacy involved in the interweaving of Ruth with various Pentateuchal narratives is so unobtrusive that it took scholars centuries to uncover these connections and allow us to benefit from this additional layer of literary brilliance. The result has been to increase our understanding and appreciation of this opus, which has so moved mankind.

6. The other connections, which have aroused considerable interest in the scholarly world, bind Megillat Ruth to Bereishit 19 (the episode concerning Lot and his daughters), Bereishit 24 (when Abraham dispatches his servant to find an appropriate wife for Isaac) and Bereishit 38 (the episode of Judah and Tamar).

7. Meishiv Nefesh 45-46.

8. See “Ruth and the Structure of Biblical History,” Vetus Testamentum XXXII (1982), 435-436.