Mourning the Churban with the Rav

Over the past several decades, the observance of Tishah B’Av has been transformed for many of us. Not long ago, we would attend shul, quickly and silently read kinot, which we didn’t understand, and leave in search of appropriate ways to spend the many long, hot hours ahead. Nowadays, most congregation rabbis deliver meaningful and moving running commentaries on kinot in their synagogues, and several web sites feature programs in which the kinot are explicated and the meaning of the day is conveyed through lectures, stories, historical background and poems.

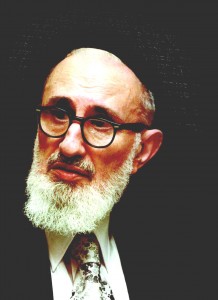

If this momentous change can be attributed to any one person, it is to Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik. Year after year, in the 1970s and 80s, in Boston, he would assemble a group of students, and deliver brilliant explanations and analyses of the kinot for the entire Tishah B’Av day. His teachings ranged from personal recollections of the lost culture of Eastern Europe to scholarly analyses of the kinot. Those who attended the long and inimitable Tishah B’Av sessions insist that it was an extraordinary experience.

If this momentous change can be attributed to any one person, it is to Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik. Year after year, in the 1970s and 80s, in Boston, he would assemble a group of students, and deliver brilliant explanations and analyses of the kinot for the entire Tishah B’Av day. His teachings ranged from personal recollections of the lost culture of Eastern Europe to scholarly analyses of the kinot. Those who attended the long and inimitable Tishah B’Av sessions insist that it was an extraordinary experience.

OU Press, together with Koren Publishers Jerusalem, has attempted to re-create those moments in The Koren Mesorat HaRav Kinot. The kinot, edited by Rabbi Simon Posner, executive editor, OU Press, and with an emotion-evoking translation by Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb, OU executive vice president, emeritus, presents Rav Soloveitchik’s commentary in a manner that will give a new dimension of relevance to the day of Tishah B’Av and will help the reader relate, not just to the day, but to the entire ongoing history of Jewish tragedy.

Excerpts from this epic commentary follow:

A DAY OF DESTRUCTION (From A’adeh ad Hug Shamayim)

A DAY OF DESTRUCTION (From A’adeh ad Hug Shamayim)

I curse this day that twice destroyed me. It is as though the paytan is saying that the day of Tisha B’Av itself has destroyed us. An awareness of the Jewish concept of time is essential for an understanding of the paytan’s point. When the Mishna (Ta’anit 26a) remarks that five events befell our ancestors on Tisha B’Av, it is saying that there is something inherent in the day of Tisha B’Av which is responsible for these tragedies. And, in fact, there are additional tragic events that occurred on Tisha B’Av subsequent to the time of the Mishna, such as the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. As far as Jewish history is concerned, Tisha B’Av is the day of tragedy, as though the day itself had somehow been responsible. There is a fatal quality to the day of Tisha B’Av–the day itself destroyed us.

The Jewish view of time is quite different from the view held by Kant and other philosophers. For them, a day has no substance of its own. It is nothing more than a frame of reference, part of a coordinate system, in which events can be located, but one cannot speak of a “bad time” or a “lonely time,” a “profane time” or a “blessed time.” For us, however, time itself is substantive and has attributes. There is such a thing as “good time,” as in a Yom Tov. The concept of kedushat hayom, the sanctity of the day of Shabbat and the festivals illustrates the Jewish concept of time. It indicates that there is substance to the day which can be filled with kedusha. The kabbalists, based on the Gemara (Shabbat 119a), say the day of Shabbat is personified by the Sabbath Queen because the day is not just a mathematical construct; it is a creation in and of itself. Based on this Jewish concept of time, we can understand how Job can curse the day of his birth (Job 3:2). There is a yom hol, an ordinary day, and there is a yom kadosh, a day which is distinct and distinguished from others. And there can be a day filled with curses and profanity.

Tisha B’Av is a day which is saturated with bitterness. In fact, it is not a date; it is a destiny. In correspondence between rabbis, Tisha B’Av is often referred to as yom hamar vehanimhar, the day which is mar and nimhar. Both mar and nimhar mean “bitter,” but nimhar is in the passive. I would suggest that the phrase be translated as “the bitter day which is saturated and endowed with bitterness.”

A MITZVA TO MOURN (From A’adeh ad Hug Shamayim)

Just as it is a mitzva on Yom Tov to encourage everyone in one’s household to be happy and rejoice (Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hil. Yom Tov 6:17–18), so too on Tisha B’Av, it is important for the head of the family to engender in the members of the household a sense of mourning. When one rejoices, one must try to share one’s joy with others, as reflected in the verse describing the festivals, “And you shall rejoice . . . you and your son and your daughter” (Deuteronomy 16:14). It is the responsibility of the head of the household to explain to the family what happened on that day. So, too, when one is grieving, one should share such feelings with others, as well.

Just as there is a mitzva of sipur yetziat Mitzrayim, the recounting of the story of the exodus from Egypt, so too is there a requirement of sipur hurban Yerushalayim, the recounting of the narrative of the destruction of Jerusalem. While the sipur hurban Yerushalayim is not a biblical obligation, the story should be told in the same manner as the story of the exodus from Egypt. In each case, the story should be related in a way that is consistent with the intelligence and understanding of the child to whom it is being told.

A DAY OF DESPAIR . . . AND HOPE (From Eikha Yashva Havatzelet HaSharon)

For we deserved extinction no less than the generation of the Flood. This passage sounds the recurring theme found in the kinot that the Beit HaMikdash served as a substitute, as collateral, for the Jewish people, and the physical structure of the Beit HaMikdash suffered the destruction that rightfully should have been visited upon the entire nation. The kina says that the Jewish people are responsible and are deserving of punishment; we are guilty, and we should have been destroyed as was the generation of the Flood. God, however, in His mercy and grace, subjected His throne, the Beit HaMikdash, rather than the Jewish people, to disgrace, abuse and destruction. It is for this reason that Tisha B’Av contains an element of mo’ed, a festival–God rendered His decision on Tisha B’Av that Knesset Yisrael is an eternal people and will continue to exist. The Beit HaMikdash was humiliated, profaned and destroyed in order to save the people.

If the Beit HaMikdash was sacred, how much more sacred were entire Jewish communities which consisted of thousands of scholars.

This concept is expressed halakhically in the character of Tisha B’Av afternoon. The second half of the day has a contradictory nature in halakha. On the one hand, the aveilut, the mourning, is intensified because the actual burning of the Beit HaMikdash commenced in the late afternoon of the ninth day of Av, and the flames continued throughout the tenth (Ta’anit 29a). On the other hand, Nahem, the prayer of consolation, is recited in the Amida for Minha in the afternoon, and not in Shaharit of Tisha B’Av morning or Ma’ariv of the preceding evening (Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayim, Rama 557:1). Similarly, tefillin are put on in the afternoon, not the morning (Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayim 555:1), and sitting on chairs rather than on the ground is permitted in the afternoon, not the morning (Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayim 559:3). In Minha, one re-inserts in Kaddish the phrase “titkabel tzlothon uvaothon, accept our prayers and entreaties” (see Beit Yosef, Tur Orah Hayim 559 s.v. veomer kaddish belo titkabel, with respect to the recitation of titkabel in Shaharit). This phrase is removed from Kaddish earlier on Tisha B’Av because the assertion that “satam tefilati, my prayer is rejected” (Lamentations 3:8) which prevails on Tisha B’Av, comes to an end at midday. Paradoxically, the moment the Beit HaMikdash was set ablaze was a moment of relief. At that moment, it became clear that God decided to take the collateral, the Beit HaMikdash, instead of pursuing the real debtor, the Jewish people. Paradoxically, once He took away the Beit HaMikdash in the afternoon of Tisha B’Av, the nehama, the consolation, could begin. Tisha B’Av is a day of limitless despair and boundless hope and faith.

THE DEATH OF THE RIGHTEOUS (From Im Tokhalan Nashim)

After being tied to racing horses. This phrase is an allusion to the story told by the Midrash about Miriam bat Baytos (Eikha Raba 1:47). She was bound to the tail of a horse, and when the horse began to gallop she was killed. This atrocity was perpetrated not only nineteen hundred years ago, but in our own time as well, during the Holocaust. In fact, it happened to a cousin of mine, Yeshayahu Glikson, whose father was Rabbi Hirsch Glikson and whose mother was the daughter of Rav Hayim Brisk. I knew Yeshayahu, who was slightly younger than I, very well. He was a righteous person and a great scholar. When the Nazis conquered Warsaw and found him and his wife, it was the first week after their wedding. The Nazis tied him to one automobile and his wife to another, and then drove off at high speed, which, of course, resulted in their gruesome deaths. This is precisely the same story as related by the kina.

(From Haharishu Mimeni)

In a sense, this kina is a continuation of the kina “Arzei HaLevanon.” In both kinot, the deaths that are described represent a double catastrophe. Thousands of Jews were killed during the Crusades. But the tragedy was not just the murder of ten people during the Roman times or the myriads during the Crusades. The tragedy was also the fact that the greatest scholars of the Jewish people were killed. In this kina, the mourning that is expressed is not just for the inhuman act of the massacre. Rather, the principal emphasis is on the destruction of the Torah centers in Germany.

The dates of these massacres are known to us. The Crusaders generally started out on their journey in the spring, and the massacres took place in the months of Iyar and Sivan, around the time of Shavuot. Even though these events did not occur on Tisha B’Av, they are included in the kinot and are commemorated on Tisha B’Av because of the principle, already noted in connection with other kinot, that the death of the righteous is equivalent to the burning of the Beit HaMikdash. If the Beit HaMikdash was sacred, how much more sacred were entire Jewish communities which consisted of thousands of scholars. These communities were also, collectively, a Beit HaMikdash in the spiritual sense. If the kinot speak about the Hurban Beit HaMikdash in the material sense, they also mourn the Hurban Beit HaMikdash in the spiritual sense, the destruction of centers of Torah and the killing of great Torah scholars. In fact, sometimes the death of the righteous is even a greater catastrophe than the destruction of the physical Beit HaMikdash.

There is an additional reason for including these kinot dealing with the massacres in Germany in the Tisha B’Av service. Hurban Beit HaMikdash is an all-inclusive concept. All disasters, tragedies and sufferings that befell the Jewish people should be mentioned on Tisha B’Av. Rashi says (II Chronicles 35:25, s.v. vayitnum lehok) that when one has to mourn for an event, it should be done on Tisha B’Av. When these kinot relating to the Crusades are recited, one should remember that the tragedies being described happened not only in 1096 but in the 1940s as well. These kinot are not only a eulogy for those murdered in Mainz, Speyer and Worms, but also for those murdered in Warsaw and Vilna and in the hundreds and thousands of towns and villages where Jews lived a sacred and committed life. The kinot are a eulogy not only for the Ten Martyrs and those killed in the Crusades, but for the martyrdom of millions of Jews throughout Jewish history.

THE WORTH OF THE INDIVIDUAL (From Oholi Asher Ta’avta)

I see an image–an image of a carpenter. He was called Elya der Stolier. He was a plain Jew, a simple carpenter, and not particularly learned. However, he knew Psalms by heart, and he used to recite certain verses at particular times. When he finished a table, he would recite the last verse of the Book of Psalms “Let everything that breathes praise the Lord” (150:6); he would recite a different verse when he started work on a project. My father used to say that Elya der Stolier was one of the lamed-vav nistarim, one of the thirty-six hidden righteous ones. Surely his home was a Beit HaMikdash, and there were thousands and thousands of Jews like him. Tisha B’Av, the day of avelut, is the day we should tell the story of the most significant experience of our lives in the last two thousand years. But the focus should not be limited to the destruction of the Holy of Holies. The focus should be every Jewish home that was destroyed, each of which constituted a BeitHaMikdash.

(From Ve’et Navi Hatati)

This kina is based on the tragic story (Gittin 58a; Eikha Raba 1:22) of the son and daughter of Rabbi Yishmael, each of whom was taken captive by a different Roman slave owner. Because the son was very handsome and the daughter very beautiful, the two slave owners decided to marry their two slaves to each other with the expectation that the union would produce beautiful and talented children who could then fetch a high price on the slave market. The son and daughter were told they would be married the next day, she to a slave, and he to a slave-girl. They were locked together for the night in a dark room, and neither could see the other. She cried all night, “How can the daughter of the High Priest be married to a slave?” He cried all night, “How can the son of the High Priest take a maid-servant for a wife?” As the morning dawned, they recognized each other and, distraught at their fate, died in an embrace.

The placement of this kina in the sequence of the kinot initially appears odd. The order of “Haharishu Mimeni” following “Arzei HaLevanon” is logical and proper. However, one would have expected that the kina following “Haharishu Mimeni,” which commemorates the martyrs of German Jewry, would have been “Mi Yiten Roshi Mayim,” the second kina pertaining to the Crusades in which Speyer, Worms and Mainz are mentioned by name and the dates of their destruction are recorded. Instead, the story of the death of Rabbi Yishmael’s son and daughter is interjected, interrupting the series of kinot about the destruction of the Jewish communities in Germany. To compound the question, one could also ask why it is necessary to interrupt the description in the kinot of major national catastrophes with a story of a young man and woman who suffered as a result of the Hurban of Jerusalem, but whose deaths did not change the course of Jewish history or the routine of daily Jewish life. The narrative flow of the kinot mourns the destruction of the state, the land and the Beit HaMikdash– all of which changed Jewish history– then the martyrdom of the ten greatest scholars of the Talmud, and then the massacre of thousands of people and the destruction of the most important communities in the Middle Ages, both spiritually and numerically. In the midst of this national commemoration of the tragedies that befell the community, the sequence of kinot is interrupted with the story of the death of two individuals.

The answer is that Judaism has a different understanding of and approach to the individual. We mourn for the individual even if he or she was not a significant person. Rabbi Yishmael, the father of these youngsters was already killed, and they were orphans. In light of the major calamities, who is responsible to remember a story about an individual young man and woman who were taken captive by some slave merchants? The answer is that we are. We have a special kina dedicated just to them, as if one hundred thousand people were involved, not just two individuals. Their lives and their deaths may not have changed Jewish history, but we suffer and remember. We do not forget the faceless, nameless individual even in the midst of national disaster and upheaval, even when telling the story of the greatest of all the disasters in our history, the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash. In this kina we mourn not for the Jews of Worms or Mainz, not for the Hurban Yerushalayim, and not for the Beit HaMikdash. We mourn for a boy and a girl who were not leaders or scholars and who did not play any major public role. They are as important as the greatest leaders. Sometimes we become so engrossed in the national tragedy that we forget the individual, and the sequence of the kinot is interrupted to highlight the worth of the individual.

A DAY TO COMMEMORATE ALL TRAGEDIES (From Mi Yiten Roshi Mayim)

The main motif of this kina, a motif found in some of the prior kinot, is that the death of the righteous is equivalent to the burning of the Beit HaMikdash. If we are to mourn for the Beit HaMikdash, we must also mourn the death of the great Torah scholars. Since the tragedy of the destruction of the Torah centers in Germany is equivalent to the Hurban Beit HaMikdash, we are justified in thinking that a special fast day should have been established to mourn for the martyrs of those massacres. However, the kina declares, we are not to add any fast day beyond Tisha B’Av to commemorate any other catastrophe, massacre or destruction.

It is interesting that a fast day was instituted on the twentieth day of Sivan by Rabbeinu Tam to commemorate an attack against the Jews, unrelated to the Crusades (Emek HaBakha of Rabbi Yosef HaKohen; Magen Avraham, Orah Hayim 580:9; Sha’arei Teshuva ibid., 9). Centuries later, when the Khmelnitsky pogroms occurred in 1648, the twentieth day of Sivan was proclaimed to be a fast day for both the persecutions against the German Jews and the Khmelnitsky persecutions. There are selihot, penitential prayers, composed for that day. Notwithstanding the tradition of observing the twentieth day of Sivan, this kina declares that Tisha B’Av is the exclusive fast day that commemorates all of the tragedies that befell the Jewish people, and that no other fast day should be instituted for this purpose.

UNENDING MOURNING (From Eli Tziyon)

Like a maiden girt in sackcloth for the husband of her youth. Just as it would be foolish to tell a woman in labor not to cry, so, too, it would be the height of insensitivity to tell a newly-wed bride whose young husband has just died, to stop shedding tears. So, too, let Zion continue to mourn over the Hurban, and do not tell her to stop.

The concept of continued, unending mourning is a special, unique aspect of avelut yeshana, mourning for a tragedy that occurred long ago, as opposed to avelut hadasha, mourning for the recent bereavement. In the case of avelut hadasha, there are limits, and Maimonides says (Mishneh Torah, Hil. Avel 13:11) that one who mourns “too much” is acting foolishly. But with respect to avelut yeshana for the Hurban, the concept of “too much” does not apply.

The message of this kina is that the kinot for Jerusalem have no end. It is for this reason that certain prayers are sung to the unique somber melody of “Eli Tziyon.” We use this haunting melody when we want to express the intensity of our loneliness and longing for the Beit HaMikdash and the strength of our faith that the redemption will come. Thus on Friday night of Shabbat Hazon, the Shabbat immediately preceding Tisha B’Av, Lekha Dodi is sung to this melody. The phrase “Enter in peace, O crown of her husband, even in gladness and good cheer,” not only refers to the coming of Shabbat, but also alludes to the rebuilding of the Beit HaMikdash. Similarly, we use this melody for the phrase in the Yom Tov Musaf Amida, “Rebuild Your House as it was in the beginning.” Our waiting for the arrival of the Messiah and rebuilding of the Beit HaMikdash has no limit. We will never be satisfied with any gift God bestows upon us if the Beit HaMikdash remains in ruins. May it be rebuilt and restored soon, in our day.