Exploring Hilchot Eruvin

Typically, Jews study halachah for two reasons. Sometimes, they study it because they are interested in its practical application to their lives—witness the explosion of halachic literature on topics of Jewish law, from business to kashrut, from blessings and prayer to Shabbat and yom tov. At other times, Jews might study halachah for a more theoretical reason. Jewish laws—especially Biblical ones—capture an aspect of God’s plan and purpose for humanity (Rambam, Temurah 4:10). Hence, the study of even non-practical halachah serves an intellectual and spiritual purpose: it helps us understand our aspirations for humanity and the values we live by.

The laws of eruv construction fall into neither of these two categories. They comprise one of only a mere half-dozen sections of the Rambam’s Mishneh Torah that famously do not connect to any Biblical imperative (Keilim and three sections in the book of Kinyan are the others), and one finds it challenging to see in the rabbinic laws of eruv any part of God’s master plan for the universe. Moreover, since most eruvin are organized, supervised and checked by a very small subset of the population, the laws of eruv construction are hardly practical for the vast majority of the Jewish population. As a result, with the small exception of the three months every seven years when Eruvin is studied as part of the Daf Yomi, this aspect of Judaism largely resides out of sight and out of mind for most Jews, as it has been, sadly, for centuries (Shiyurei Knesset HaGedolah, Yoreh De’ah 245).

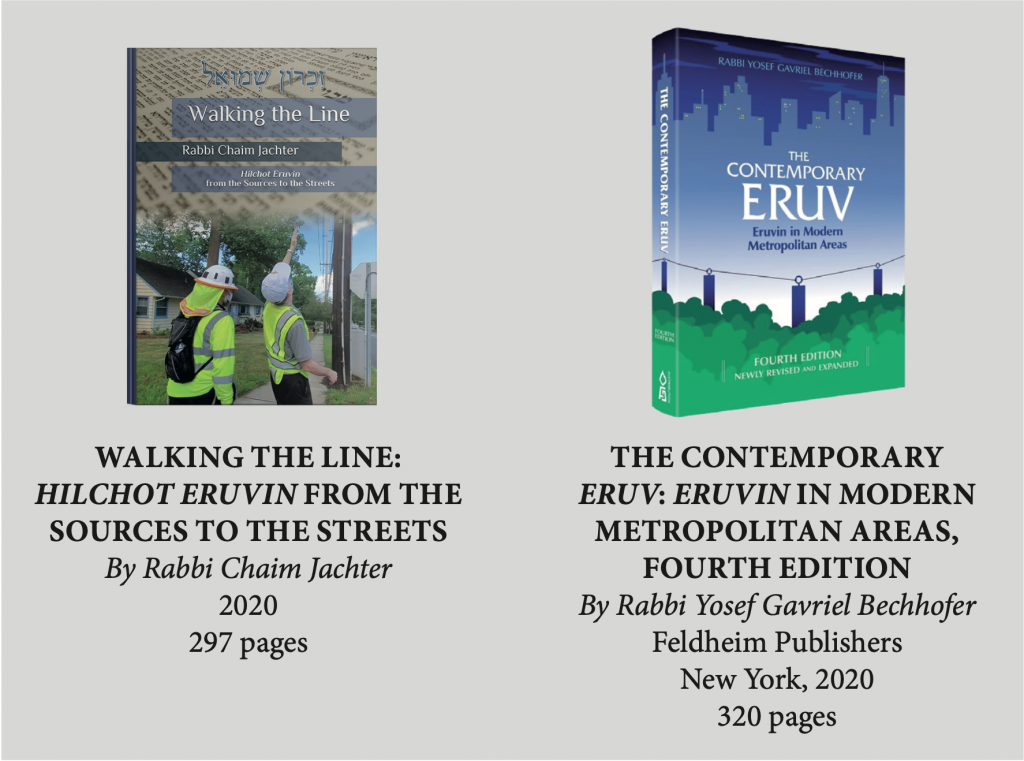

Rabbi Chaim Jachter and Rabbi Yosef Gavriel Bechhofer have each recently authored new or updated halachah handbooks on eruvin. Walking the Line: Hilchot Eruvin from the Sources to the Streets and The Contemporary Eruv: Eruvin in Modern Metropolitan Areas, respectively, provide a unique third reason to be motivated to learn this understudied area of Jewish law. Reading these books, one realizes that the study of eruv is at its core the study of community, and that the development of Jewish societies and Jewish living is best captured through the history of eruvin. Even if the reader is not interested in the practicalities of the two vertical posts and horizontal wire that become a theoretical door or wall for a community, he or she may be interested in the stories of Jewish communities that recur throughout both Rabbi Jachter’s, and to a lesser extent, Rabbi Bechhofer’s, books.

How is community life different in Israel, the Jewish State, as opposed to the Diaspora? The eruv gives a clue when we notice that eruv wires and posts are straighter in Israel because the Jewish, even if secular, government wishes to support Jewish living (Jachter, 202-205).

What are the implications of young Jews leaving their home communities for campus life? The eruv gives a clue when we consider the necessities of adopting possible leniencies on campus: the Yeshiva University eruv and its sagging wires (129-136), Yale University and the stringency of the Tevu’ot Shor (146-155), and Princeton University and the question of the horizontal wire that crosses the vertical posts instead of resting above them (141-145).

Jews today send their children to summer camps, and so eruvin must be built—for example, at Camp Morasha (with horizontal posts almost reaching the ground [107-108]).

More broadly, the story of eruvin is the story of Jewish communities on different continents (167-179); in environments ranging from rural (navigating the question of cornfields [156-160]) to super-urban (cities with more than a million residents [10-21]); weathering storms (233-239), price wars (resulting in fewer lechis [doorposts] needed [213-215]), and community strife (206-212); and, on the positive side, exhibiting community volunteerism (217-222).

The topic of eruv also captures the range of opinions between American Ashkenazim, Sephardim (with a different standard for a reshut harabim [public domain] 180-195), and Chabad rabbis (insisting on smaller tzurot ha’petach [doorframes] 196-201).

In a scholarly essay appended to the fourth revised and expanded version of The Contemporary Eruv (Bechhofer, 220-249), the author is explicit about this point: an eruv is a marker of a community more than it is an artifact of Jewish ritual or Jewish law. He stresses that the infrastructure of an eruv does not serve a political purpose or even a religious purpose. Instead, it marks secular public space. Thus, the study of the construction of an eruv is less a religious study and more a remark on the contours of a religious community’s physical space instead.

The presentation styles of the two works are slightly different and may appeal to different audiences. Though each work stands alone and is simultaneously erudite enough for a scholar yet accessible to the layman, they provide for different learning experiences. Rabbi Jachter’s work reads seamlessly, with few distracting footnotes and with illustrations on the page of the text when needed. Rabbi Bechhofer’s work may be preferred by a more scholarly audience, with long discursive footnotes, occasional lengthy quotations of the original Hebrew sources, and an appendix of more than 100 color photographs capturing the real-life nature of eruv infrastructure. In addition, the two rabbis use slightly different methodologies to reach their final halachic rulings. Both works cite all the relevant Acharonim; however, Rabbi Jachter concludes with the ruling of his rebbeim (Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mordechai Willig) on nearly every other page, while Rabbi Bechhofer quotes posekim of the previous generation and rules based on their consensus.

The two works are actually in dialogue with each other on many important, substantive issues. Rabbi Jachter devotes a major section to Rabbi Bechhofer’s objection to the “side top wire” (Jachter, 110-116), and another major section to Rabbi Bechhofer’s insistence that there be a vertical post on every utility pole (83-94) to which Rabbi Bechhofer responds in his fourth edition (Bechhofer, 177-180). Even when they disagree, however, the esteem the two rabbis have for each other is clearly demonstrated throughout each work. Rabbi Bechhofer reproduces Rabbi Jachter’s eruv guidelines and calls them “significant and essential” (194-219), and Rabbi Jachter quotes Rabbi Bechhofer’s earlier work with respect. Ultimately, the two works have the same goal in mind—the best possible Torah observance by the Orthodox Jewish community.

Both works are recommended to those looking to learn the basics of the laws of eruv construction in the Jewish community or those seeking to understand what it means to live in a Jewish community anywhere in the world in our current day and age.

Rabbi Dr. Yaakov Jaffe is the dean of Judaic studies at the Maimonides School and rabbi of the Maimonides Kehillah in Brookline, Massachusetts.