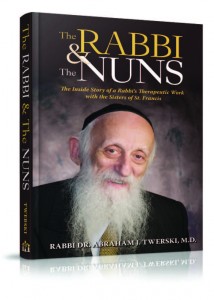

The Rabbi & The Nuns: The Inside Story of a Rabbi’s Therapeutic Work with the Sisters of St. Francis

The Rabbi & The Nuns: The Inside Story of a Rabbi’s Therapeutic Work with the Sisters of St. Francis

The Rabbi & The Nuns: The Inside Story of a Rabbi’s Therapeutic Work with the Sisters of St. Francis

By Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski

Mekor Press

Brooklyn, 2013

190 pages

Reviewed by Steve Lipman

A psychiatrist and Chassidic rabbi, Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski has established himself as a master of crossing boundaries—writer of inspirational stories and of profound scholarship; friend of prominent Jewish leaders and of non-Jews of note (such as the late Peanuts cartoonist Charles Schulz); Orthodox insider and bridge to the wider Jewish community.

In his latest book (he’s authored more than five dozen), Rabbi Twerski writes about a little-known working relationship, as a therapist and sometimes-religious-mentor, he conducted for two decades with a group of nuns (and some priests) in Pittsburgh, where he established the Gateway Rehabilitation Center, over which he now serves as medical director emeritus.

“A long-term relationship between an Orthodox rabbi and nuns is a bit unusual,” he writes in the book’s introduction in a classic example of understatement. “When I walked down the street in the company of the sisters, many heads turned in disbelief.”

A reader gets the feeling that the rabbi, an iconoclast in the frum community, enjoyed making heads turn.

He tells his unusual tale with stories from his family and from the wise men of Chelm that color many of his earlier books.

The nuns were from Pittsburgh’s St. Francis General Hospital. The rabbi was in a psychiatric training program at the University of Pittsburgh, developing what grew into his internationally recognized expertise in dealing with alcoholism and similar addictions. It was the early 1960s. Part of Rabbi Twerski’s training included two months at the psychiatric unit of St. Francis, run by the Sisters of St. Francis, “the only [psychiatric] emergency service in the tri-state area.”

The head of the university’s Department of Psychiatry, Dr. Henry Brosin, asked Rabbi Twerski to take over the vacant directorship of St. Francis’ Psychiatric Department.

“You think I’m meshugah,” Dr. Brosin said.

“You said it. I didn’t,” Rabbi Twerski replied.

The rabbi agreed to meet with Sister Adele, the hospital administrator. “I had no intention of taking the position at St. Francis,” Rabbi Twerski writes. He used the Orthodox-Jew card: he’d be unreachable “twenty-six hours” every week, on Shabbat.

“Dr. Twerski,” the sister said, “we would never think of calling you on your Sabbath.”

Next, the away-in-Israel ploy—the Twerskis were going there for two months. “We’ve waited this long [for a qualified director], we can wait a few more months,” the sister said.

“Let me think it over,” Rabbi Twerski said as he left Sister Adele’s office.

“Dr. Twerski,” she said, “I know you are going to be our director of psychiatry. Our Savior sent you to us.”

“I decided to give it a try for one year,” Rabbi Twerski writes. “That ended up being twenty years.”

During that time, he worked with patients admitted under the hospital’s turn-nobody-in-need-away policy, with nuns who were having a difficult time adjusting to the Vatican’s liberalized policy that offered a wider choice of careers in the Church beyond the standard teaching positions or hospital work, and with priests and nuns who had various problems that required psychiatric intervention. During that time, Rabbi Twerski picked up a working knowledge of Catholic procedures. He also established solid friendships in Catholic circles.

To treat his wide range of patients, Rabbi Twerski employed a combination of medical training, rabbinical insights, street smarts and common sense. He became the go-to psychiatrist in Pittsburgh’s Catholic community. The cases of the men and women he saw, and usually helped, constitute the bulk of his book.

Eventually, he left St. Francis Hospital to concentrate on his own rehabilitation center. “I was fortunate in being exposed to people and things I could learn from,” he writes.

His encounters with Catholic clergy gave him respect for a faith group with which most Orthodox Jews have little relationship, he writes. “World history is replete with tragedies wrought by religious differences. I believe that attributing disagreements, wars and the inability to coexist peacefully to religious differences is nothing but rationalization, an invoking of religion to explain away hostility and selfishness that stems from totally different sources. Religious differences serve as a convenient scapegoat, and one tries to justify one’s aggression or violation of the rights of others by ascribing one’s motivation to defense of one’s religion.”

Neither Rabbi Twerski nor the priests and nuns with whom he came in contact glossed over the “thorny . . . relationship of the church to Jews throughout history. However, we were working on being of service to humanity, and our feelings about the past were not going to deter us from our determination to work together.

“The unique experience of ‘the rabbi and the nuns’ set an important example of what can be if you want it to be,” Rabbi Twerski writes. “This was a very rewarding experience for all of us. Hopefully, the nuns benefited from our treatment. I know that we benefited immensely from the relationship.”

Steve Lipman, a staff writer for the New York Jewish Week, is a frequent contributor to Jewish Action.