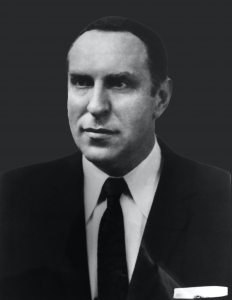

Shtadlanim: Elimelech Gavriel (Mike) Tress (1910-1967)

It is one of history’s ironies that the Agudah movement in America came about almost entirely through the magnetic personality of a clean-shaven college graduate who never spent a day in any yeshivah. Mike Tress was twenty-one years old when he first walked into the Rodney Street branch of Zeirei Agudath Israel in 1931, after reading an article on Agudath Israel by Moreinu Yaakov Rosenheim, the world president, in the New York Public Library.

Within six months he had been elected president of the branch, over the strenuous objections of most of the older members. But as Louis Septimus, one of his original opponents, subsequently wrote, the older members who stayed away that night rendered a signal service by paving the way for the transformation of a shalosh seudos club into a world movement.

Gershon Kranzler, who had recently emigrated from Germany, became Mike’s closest assistant in building up Pirchei chapters across New York City, and then in other cities. He described the impact of Mike’s words on a small group of boys gathered for a melaveh malkah in a forlorn shul attic:

He addressed them, seriously and sincerely, and the ragged little children were lifted above their small, confining worlds. . . . His sincerity struck home when he waved the magic wand of his “chaverim”. . . He made all of us, the Pirchim from East New York, the chaverim from the Bronx, the West Side, or Bushwick, feel like soldiers, recruited into the ranks of Hashem’s army, the Maccabees of today.

“He taught us that Judaism is not just a tradition, but our most precious possession, a possession for which he had to be prepared to fight and pay a price,” remembers Torah Vodaath’s Rav Moshe Wolfson. And when the remnant of the European Torah world began to arrive in America, they found a group of young American Jews who had been trained to look upon them as the true leaders of the Jewish people. Those youngsters were prepared to venerate the newcomers because their first hero had pronounced the names of the leaders of European Jewry, in forum after forum, year after year, with such awe and reverence.

Many said of Mike that they never met someone who suffered as he did from another Jew’s pain, and those closest to him attest that he was never the same after what he had experienced in the DP camps.

Above all, Mike channeled their youthful idealism into life-saving work. Zeirei Agudath Israel worked endlessly to procure visas for Jews trapped in Europe throughout the war, prepared the applications for seventy Special Visitors Visas, which brought to America leading roshei yeshivah, helped to procure thousands of fake South American passports, conducted endless fundraising campaigns (including closing the yeshivos for three days) in response to Rabbi Michoel Ber Weissmandl’s pleas for funds for his rescue schemes. The six-foot-long forms for visas had to be typed out on manual typewriters, in quadruplicate, by young volunteers.

After the war, volunteers worked around the clock, including yeshivah students after night seder or returning from college night classes, packing cartons sent through the army post office to Orthodox soldiers in Europe for the she’eris hapleita in the DP camps. Some were still existing on less than 1,000 calories a day, and felt abandoned by world Jewry, even after the torments they had undergone.

Mike himself traveled to Europe under the auspices of UNRRA in late 1945 and spent more than a month with the she’eris hapleita, sleeping together with them on wooden pallets in extremely overcrowded lodgings. When he returned, he ignited a huge crowd—500 were turned away—with an account of his experiences and of his audience’s obligation to do everything possible to help them rebuild their lives.

Mike Tress (far right) with Hungarian refugees, December 1956. Courtesy of Agudath Israel of America Archives

Many said of Mike that they never met someone who suffered as he did from another Jew’s pain, and those closest to him attest that he was never the same after what he had experienced in the DP camps.

In 1939, Mike quit his job as an executive at S.C. Lamport, a large textile firm, to devote himself full-time to the rescue work of Zeirei. During one of Agudah’s recurring financial crises in the 1950s, an accountant appointed by the State of New York to review the organization’s books found that Mike had over seventeen years emptied his bank account, then sold off his stock portfolio, and finally mortgaged his home to fund the life-saving work of the Agudah, despite having a family of twelve children.

Toward the end of his life, he lacked the money for a heart operation, which offered his only hope of recovery. One of his daughters read in the paper that a shoe polish company of which he had been one-third owner had been sold for $3,000,000. “Think how different it would have been had you held on to those shares,” she remarked to her father.

Mike’s only response: “Baruch Hashem, how different.”

Jonathan Rosenblum is a journalist who writes for several Orthodox media publications, and has a weekly column in Mishpacha.

More in This Section

The Shtadlan in Jewish History: A Conversation with Dr. Henry Abramson by Faigy Grunfeld

Rabbi Herschel Schacter by Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter

Dr. Jacob Birnbaum by Sandy Eller

Irving Bunim by Merri Ukraincik

Rabbi Joseph Karasick by Sandy Eller

Zev Wolfson by Jonathan Rosenblum

Dr. Marvin Schick by Steve Lipman

Rabbi Herman Naftali Neuberger by Aviva Engel

Rabbi Moshe Sherer by Jonathan Rosenblum

Moses Feuerstein by Leah Lightman