The First and Last Time I Saw Nechama

First Encounter

I first met Nechama Leibowitz in the summer of 1967. I had come to Israel to volunteer during the Six-Day War and decided to stay for a year to take courses in Jewish studies at Hebrew University. A friend insisted I meet Nechama, who could suggest a program of studies for me. Coming from a religiously non-observant home, I wanted to make up for having almost no serious Jewish education. My friend, who herself was not observant, told me that Nechama would meet me at noon in the university cafeteria and I should ask anyone there to point her out since “everyone knows her.”

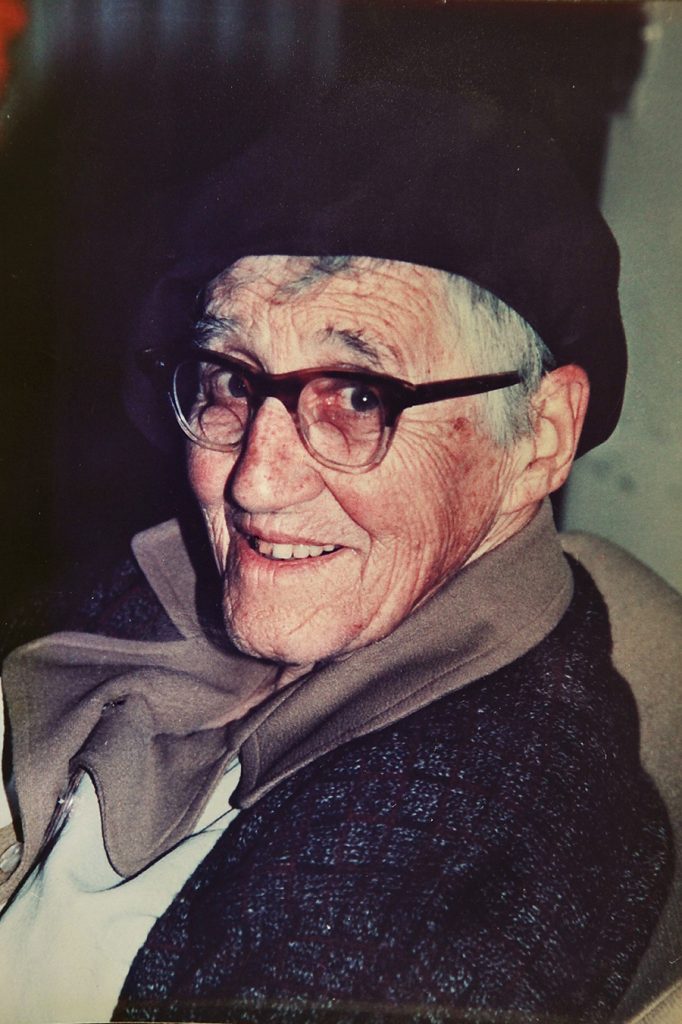

I found her in the cafeteria, identifying her by her trademark beret. Ever practical, she told me to take a tray and get some lunch. “If you want to study Torah, you have to eat,” she said, inverting the usual conception of Torah as nourishment. She told me to register for her course on Sefer Shemot in easy Hebrew for American students, and wrote up a list of courses at Hebrew University in some basic Jewish sources: a class on beginning Talmud for literature majors; an introduction to the Kuzari, Guide for the Perplexed and Sefer HaIkarim; a seminar on Hebrew literature; and a course on Jewish history.

Sometime later I was introduced to her nephew, Elhanan Leibowitz, and we were married the following year in Jerusalem.

How the Gilyonot Originated

Born in 1905 in Riga, Latvia, Nechama received an extensive secular and Jewish education in Germany after her family moved to Berlin. In 1930 she married her uncle, Lipman Yom Tov Leibowitz, and he insisted she finish her doctorate in Bible from the University of Marburg before they made aliyah. She earned her doctorate and the couple moved from Berlin to Jerusalem. Except for a brief visit back to Germany to help her parents make aliyah, Nechama refused to ever leave Eretz Yisrael.

In 1942 she was asked to give a course of Torah study in Jerusalem for young women from the religious kibbutz movement. She would assign the students homework questions on the parashah, usually comparing different commentators. The written answers of the students were returned to them marked “correct,” “very good,” or “incorrect”—with clarifying explanations. Yael Unterman, in her comprehensive biography of Nechama (Nehama Leibowitz: Teacher and Bible Scholar [Urim, 2009], p. 51), describes what happened in the summer of 1942:

“After the young women returned to their kibbutzim, a rare, if not unique, event in the history of education occurred: though the school year was over, the students asked for more homework! These young women wrote, asking to continue the questionnaires under her supervision. More than happy to oblige, she mailed the first sheet to the women at their respective kibbutzim.” Thus, necessity mothered the invention of the unique innovation that Nechama became known for: a weekly worksheet filled with questions on the Torah portion, which she termed “Gilyonot L’iyun B’Parashat Hashavua.”

I found her in the cafeteria, identifying her by her trademark beret. Ever practical, she told me to take a tray and get some lunch. “If you want to study Torah, you have to eat,” she said, inverting the usual conception of Torah as nourishment.

Word spread about this one-woman voluntary correspondence course, and over the years hundreds subscribed to the Gilyonot. Answers were submitted along with self-addressed, stamped envelopes so Nechama could return them with her responses marked in red ink. From 1942 until 1972, she disseminated weekly Gilyonot, amounting to some 1,500 worksheets; many weeks she also typed out a guide sheet she referred to as Alon Hadrachah, containing supplementary material. The Gilyonot were typed on a manual typewriter and mimeographed. Nechama’s nephews and nieces were drafted to hand-address envelopes, lick stamps and trudge to the post office. During the Gilyonot’s early years, Nechama would instruct students to look up specific commentaries and she provided the relevant chapter and verse for the question under discussion. She subsequently decided to include the commentaries to make it easier for soldiers who were studying her Gilyonot. For Nechama, even the lowliest private in the IDF was top brass in her eyes, especially those who wanted to study Torah while enlisted or in the reserves.

For many years, I sent in my responses to Nechama’s Gilyonot. My husband and I did not live in Jerusalem and this was a way for me to continue to study Torah with Nechama. Though I had become a niece by marriage, she cut me no slack and I received my share of comments like “you completely misunderstood the question” or “absolutely wrong,” along with some “very goods” and even a rare “excellent.”

Nechama was reluctant to publish her answers to the Gilyonot in a book. She considered her primary mission to teach, lecture and put out the Gilyonot; publishing books was a sideline. Nevertheless, she was prevailed upon to publish, and thus her “Studies” series on the five books of the Torah came out in Hebrew, which was subsequently translated into English and other languages. A number of her other works were printed as books, and her Gilyonot were published posthumously in book form by several of her students. For example, Yitshak Reiner and Shmuel Peerless published Studies on the Haggadah from the Teachings of Nechama Leibowitz (Hebrew and English), containing Gilyonot questions related to the text of the Haggadah, including their suggested answers.

Last Encounter

The last time I saw Nechama was a few weeks before Pesach 1997, at the weekly shiur held in her cramped Jerusalem apartment for a few dozen aficionados. I came early and she was resting somewhat listlessly. She asked me to assemble a year’s worth of Gilyonot which were filed wall-to-wall in folders according to the weekly sidra. I performed the task slowly because I did not know the order of the parshiyot by heart. Flabbergasted, Nechama chided me for my lack of knowledge and then resumed resting. The shiur participants entered, and she rose to hand out the Gilayon that she had chosen to teach. Suddenly she came to life; she was her old animated self, giving her trademark interactive shiur. The Gilayon topic was “The Breaking of the Tablets” in Parashat Ki Tisa, and she lingered on the Meshech Chochmah, one of her favorite commentaries. Even though she was weak, she brooked no foolish answers from the participants. The following day Nechama was hospitalized for the last time, and she returned her soul to its Maker on the fifth of Nisan, 5757 (April 12, 1997).

My first encounter with Nechama focused on the importance of a good lunch before engaging in Torah study; it seems to me that Nechama, with her penetrating questions and thought-provoking insights, nourished thousands with her Torah.