On Mothers

“The Jewish Area” by Elena Flerova. Copyright by Alexander Gallery (ATV Gallery INC). www.alexandergallery.biz.

It is no secret that behind every great Jewish leader is a great Jewish mother. Eliyahu Krakowski presents the writings of various gedolim who speak with love and devotion about their mothers and the profound influence they had on their lives.

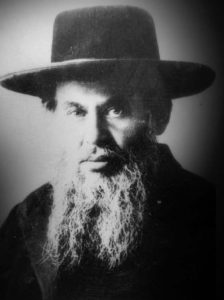

Rabbi Yissachar Shlomo Teichtal (1885-1945)

I remember when I was eight years old, and I was learning Chezkas Habatim [in Bava Basra], my mother would wake up early on Friday to bake for Shabbos, and she would bake a small, sweet cake just for me, since I was learning Torah . . . to make the Torah dear in my eyes and make my heart excited for our holy Torah. One time, her baking was delayed, so that when I came back from shul after Shacharis, my cake had not yet been baked. I asked, “Mommy, Mommy, where is my cake?” because I was hungry. My mother responded wisely, “What can I do, dear son, the cake is still in the oven. But I will give you advice to quiet your hunger: Know, my son, that the holy Gemara has the effect of quieting hunger and satisfies living beings just like bread and [like] the cake that I am making for you. Take the Gemara and review what you studied this week, and you will be full. You will see that I am correct and you will not feel any hunger. On the contrary, you will taste honey sweeter than from the comb, a taste even sweeter than the cake.”

Hearing her pleasant words, spoken with a smile and with warmth, burning with love for the Torah, to the heart of a small child to excite his heart for our holy Torah, I had no doubt that what she said was true and I believed that it was actually so—that when a person is hungry and he sits down to learn, he becomes satisfied. I went energetically and took the Gemara and reviewed the week’s lessons with great desire until I truly forgot my hunger, and even the cake was forgotten. In the meantime, the cake finished baking, and while I was learning my mother came and brought me the cake and said, “Eat your bread with joy” (Koheles 9:7). With methods like these my parents endeared the Torah to me, and this is what gave me the strength to withstand all the trials that have come over me until this point. . . .

Responsa Mishneh Sachir, Introduction (trans.)

Rabbi Eliezer Waldenberg (1915-2006)

The naming of a Talmudic sefer after my mother and teacher, a”h, is not merely an artificial grafting but rather is a fitting combination, because she was totally immersed in the waters of Torah knowledge, and her whole existence was wrapped up in Torah and yiras Shamayim. One could sense in a tangible way how she experienced the taste of the World to Come in this world while sitting and listening to her husband and her children studying Torah, either participating through an awed silence, or while reading works of musar such as Chovos HaLevavos and Menoras HaMaor, or taking part by recounting words of aggadah, musar and derush on the weekly parashah. A singular inner peace spread over her at such times and an exalted spiritual glow displayed itself prominently across her features. As long as her soul was still within her, she was devoted entirely to noble pursuits such as these, to the point that speaking of Torah, yiras Shamayim and good middos served as a healing balm to give her the will and desire to live even in the midst of the most difficult moments of her illness. It was clear that the Chovos HaLevavos which she studied day and night had taken control of all her limbs, and that the Menoras HaMaor which she reviewed assiduously shone its light through her entire body and illuminated the darkness of her physical suffering. Through this, she was able to ascend above her physical existence and so-to-speak proclaim, “Even as I walk through the valley of the shadow of death I will not fear because You are with me. Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me” [Tehillim 23:4]. She strengthened and encouraged all of us, telling us not to worry so much about her worsening condition, since the God we serve on this earth is the same God who controls all worlds, and therefore even after her passing, we would still have the connection through worship of the one God who watches over us all. How deep and multi-layered are these lofty words. . . .

I will never forget the majesty which spread over her on the last Seder of her life. We were all surrounding the Seder table. With supreme strength granted to her as she lit the holiday candles with such deep emotion, accompanied by awe-inspiring prayer to her Creator, she sat up in her bed, participated in the Seder and listened attentively to everything which was taking place. When one of her children whispered to her that perhaps the noisy arguments over divrei Torah were too much for her to bear, she answered tenderly and sensitively: “Noise such as this, exchanges over divrei Torah, I can bear.” She sat this way, encouraging until the end, and the participants during these holy hours almost forgot about the critical condition she was in.

Ramas Rachel, Introduction (Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 5) (trans.)

You, Ima, were formed from the substance of lions. You were a spiritual descendant of Yitzchak Avinu—a soul which was made to beat by the attribute of gevurah, in all of its manifestations.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe: Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902-1994)

On the day of a yahrtzeit, it is customary to talk about the conduct of the person who is remembered so that we may take instruction from their lives [sic]. . . . In speaking of a righteous woman who did so many important and good actions in her lifetime it is difficult to choose one incident to relate. . . . The exile that they experienced (my father and mother) began when the old regime in Russia was replaced. At that time they were in a state of exile, or siege, in their own city. Of course it became incomparably more acute when they were actually driven from their home and exiled in a strange and distant land. . . . [Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and his wife, Rebbetzin Chana, first lived in Chi’ili, Russia. With the onset of World War II, many refugees ended up in the Kazakhstan region, including Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and his wife.]

First of all, the fact that my mother actually joined my father in exile is in itself a lesson for us. My father was the one against whom the decree of banishment was issued by the authorities. My mother was really not obliged to leave her home, or her city and journey to the distant, forsaken land. She chose to do so out of her good will and with a severe determination, because she wanted to be close to, and give support to, her husband in his exile . . . . In that nefarious place and under external circumstances she did, however, undertake a painstaking practice which involved special sacrifice and was intended to facilitate the dissemination of my father’s teachings to the masses.

My father’s whole being and life was his Torah study; he labored in Torah, especially the esoteric teachings of Torah, the Kabbalah. For himself the mental activity and the words of Torah would have sufficed. But to disseminate his teachings to others—that needed transcription. It had to be recorded in ink on paper—but what to do? No such thing was available—there was no ink to be had in the lands of exile.

Here my mother came into the picture. In addition to helping my father in all his usual needs, she got involved in assuring the recording of my father’s Torah for posterity. She learned how to make ink, and she personally scavenged for the necessary grasses and herbs, which she painstakingly gathered with great difficulty. To these she added some special chemicals from which she concocted home-made ink. It was with that ink that my father was able to record his teachings on paper.

As a result of this, she created the possibility that today we are able to disseminate my father’s teachings in print, so that still today, in 5746 [1986], many Jews may study his teachings and commentaries on the esoteric aspects of Torah as illuminated through the understanding of Chassidus Chabad. For this we pay homage to the woman whose yahrtzeit we observe today . . . .

Shabbos Parashas Vayeilech, yahrtzeit of Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson, sixth day of Tishrei, 5746 (1986); excerpted from chabad.org.

…You found the wherewithal to pave a path to your father’s heart and explain to him the value and necessity of what you were doing.

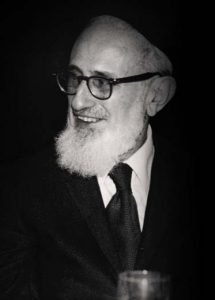

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903-1993)

People are mistaken in thinking that there is only one Massorah and one Massorah community; the community of the fathers. It is not true. We have two massorot, two traditions, two communities, two shalshalot ha-kabbalah—the massorah community of the fathers and that of the mothers. “Thus shalt thou say to the house of Jacob (the women) and tell the children of Israel (the men)” (Exodus 19:3); “Hear, my son, the instruction of thy father (mussar avikha) and forsake not the teaching of thy mother (torat imekha)” (Proverbs 1:8), counseled the old king. What is the difference between those two massorot, traditions? What is the distinction between mussar avikha and torat imekha? Let us explore what one learns from the father and what one learns from the mother.

One learns much from father: how to read a text—the Bible or the Talmud—how to comprehend, how to analyze, how to conceptualize, how to classify, how to infer, how to apply, etc. . . . One also learns from father what to do and what not to do, what is morally right and what is morally wrong. Father teaches the son the discipline of thought as well as the discipline of action. Father’s tradition is an intellectual-moral one. That is why it is identified with mussar, which is the Biblical term for discipline.

What is torat imekha? What kind of a Torah does the mother pass on? I admit that I am not able to define precisely the massoretic role of the Jewish mother. Only by circumscription I hope to be able to explain it. Permit me to draw upon my own experiences. I used to have long conversations with my mother. In fact, it was a monologue rather than a dialogue. She talked and I “happened” to overhear. What did she talk about? I must use an halakhic term in order to answer this question: she talked me-inyana de-yoma. I used to watch her arranging the house in honor of a holiday. I used to see her recite prayers; I used to watch her recite the sidra every Friday night and I still remember the nostalgic tune. I learned from her very much.

Most of all I learned that Judaism expresses itself not only in formal compliance with the law but also in a living experience. She taught me that there is a flavor, a scent and warmth to mitzvot. I learned from her the most important thing in life—to feel the presence of the Almighty and the gentle pressure of His hand resting upon my frail shoulders. Without her teachings, which quite often were transmitted to me in silence, I would have grown up a soulless being, dry and insensitive.

The laws of Shabbat, for instance, were passed on to me by my father; they are a part of mussar avikha. The Shabbat as a living entity, as a queen, was revealed to me by my mother; it is a part of torat imekha. The fathers knew much about the Shabbat; the mothers lived the Shabbat, experienced her presence, and perceived her beauty and splendor.

The fathers taught generations how to observe the Shabbat; mothers taught generations how to greet the Shabbat and how to enjoy her twenty-four hour presence.

In this excerpt from “A Tribute to the Rebbitzen of Talne,” Tradition 17 (spring 1978): 73-83—a eulogy by the Rav about Rebbetzin Rebecca Twersky, the mother of his eldest son-in-law—the Rav describes his relationship with his mother.

[My mother] taught me that there is a flavor, a warmth, to mitzvot. I learned from her the most important thing in life—to feel the presence of the Almighty and the gentle pressure of His hand resting upon my frail shoulders.

Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein (1933-2015)

My mother was born in Telz. For her, Telz—the site of one of the major Lithuanian yeshivot—was not only a birthplace, but a source of influence. My grandfather, Rabbi Abchik Schwartz, was the secretary of the yeshivah, and the family lived in its courtyard. Not infrequently would my mother recall how the sound of the shofar or the response of “Amen, yehei shemei rabbah” in the yeshivah could be heard clearly in her house. The feeling of connection to the nobility of the world of Torah and the spirit which characterized Lithuanian Jewry at its best was part of my mother’s blood and soul. Fifty years after immigrating to the West, the word “etzleinu, for us” always referred to us Litvaks. She was raised in the shade of wisdom and merited to see a number of the gedolim of that time. The roshei yeshivah of Telz she, of course, knew from up close—my grandfather would take a walk every day with Rabbi Chaim Rabinowitz [Rabbi Chaim Telzer], and it was said that one could set a watch based on the time they departed and returned. But she also met by happenstance with other gedolim. She saw Rabbi Boruch Ber [Leibowitz] when they both escaped to Minsk during the First World War; she ate with Rabbi Elchonon [Wasserman] at the Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna [in 1923]; and she was friendly with a number of individuals whose stars rose in the Torah world in the course of time—when I was young, I heard the Ponovezher Rav, whom my mother knew as Rabbi Yoshe Koller, refer to my mother by her first name; she was greatly respected by Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetsky, who was a friend of the whole family; she was part of the circle in which my teacher Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner was active at the beginning of his life. Later on, I remember how when I was a guest of my future father-in-law, I heard him say about my mother, before he got to know and appreciate her: “Nu, about Aharon’s mother, Rabbi Dovid Lifshitz said that she is half a rosh yeshivah.” And in fact, my mother was almost the only unmarried woman who would walk into the famed Talmud Torah in Kelm. . . .

My purpose is not to elaborate on history, rather to sketch a personality. The central facet can be clearly defined: You, Ima, were formed from the substance of lions. You were a spiritual descendant of Yitzchak Avinu—a soul which was made to beat by the attribute of gevurah, in all of its manifestations. Such courage and such strength! In matters small and large. Approaching the age of forty, you decided it was time to learn how to ride a bicycle—and you did. A decade later, when you decided that the school you were teaching in was not treating you properly, you chose to abandon the profession entirely and enter a new field. Since you had no training for this, you began studying bookkeeping and accounting, and you stubbornly persisted until another teaching opportunity came your way. . . .

At my bar mitzvah, in the presence of Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner, Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetsky and Rabbi Dovid Lifshitz, who spoke if not you? And later on in life, who traveled from the bowels of Brooklyn each week to hear the Rav’s shiur in Manhattan? Who traveled for almost an hour and a half each way to Yeshiva University to hear lectures on Israeli and Babylonian Aramaic from my teacher Rabbi Michael Bernstein? You, Ima.

Such courage and such strength! Equally for relatively trivial matters and major ones. It was not easy in Lithuania of the 1920s for a young woman to leave her home to acquire a Western education—in particular, when this was not done out of rebellion against the world of Telz and Kelm, God forbid, but with pride in your Lithuanian heritage and a desire to complete it, deepen it and broaden it. Despite the difficulties, you made the decision; and once the decision was made, you found the wherewithal to pave a path to your father’s heart and explain to him the value and necessity of what you were doing.

After making the difficult adjustment to a new country, our family was finally making ends meet. In the middle of our second year living in Chicago in the 1940s, my mother was present at the wedding of one of the educators in the community, at which the bride walked down to the chuppah to the tune of “Here Comes the Bride.” My mother was shocked, though she contained herself. But when she came home she definitively announced,

“My children will not be educated in this place.”

You stubbornly insisted, from the time of your youth in Lithuania until making aliyah at the age of seventy, on speaking Hebrew in foreign lands, whichever they were. In your house and while teaching, in Paris and in New York, you did not allow another language to pass your lips. The names you chose for your children were another testimony to your loyalty. You would tell with pride about how in the hospital in Paris they thought you had suffered a head injury when, despite the strong opposition of the certified officials who claimed that in France you must give French names, you consistently maintained that your children would not be named Jacques or Madeleine but Shoshanah, Aharon and Hadassah. . . .

As an orphan, I wish to say a few parting words.

First of all, thank you! For all that you sacrificed to bring me—to bring us—both to life in this world and in the World to Come. You not only gave us the strength and ambition to grow, you also infused in us the substance, knowledge and values to do so. You set before us challenges and developed in us the personal and intellectual tools to deal with them. You were not only my mother, but also my rebbe and teacher—both as one who implanted in me Torah knowledge, simply put, and as one who shaped a personality which longs for acquisition of such knowledge, in all its breadth and depth. . . . You implanted in us a thirst for broader horizons and allegiance to truth, the truth of Torah and yirat Shamayim, the will and the ability to ascend from the rut of prevailing mediocrity . . .

In the closing lines of Masechet Moed Katan, we find: “Rabbi Chiya bar Ashi said in the name of Rav: Talmidei chachamim have no rest even in the World to Come, as it says [Tehillim 84:8], ‘They go from strength to strength [me’chayil el chayil], every one of them appears before God in Zion.’” For you, Ima, a true talmidat chachamim [student of the wise], there was not much rest in this world. It was a world of chayil, strength, according to both meanings of the word: courage and achievement. You remember, Ima, how on Shabbat evening after a particularly busy Friday, you would stand by the Shabbat table and announce, with satisfaction and with a smile, “This week I was really an Eshet Chayil.” In this world of action, you were truly an Eshet Chayil; and so will you continue to be in the world of recompense . . . .

“Ima,” (trans.) The original can be viewed in Hebrew at http://asif.co.il/?wpfb_dl=5818.

Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski is associate editor of OU Press.

Also in this section: