Bravo!

Illustration: Nachman Hellman/www.nachmanhellman.com

Illustration: Nachman Hellman/www.nachmanhellman.com

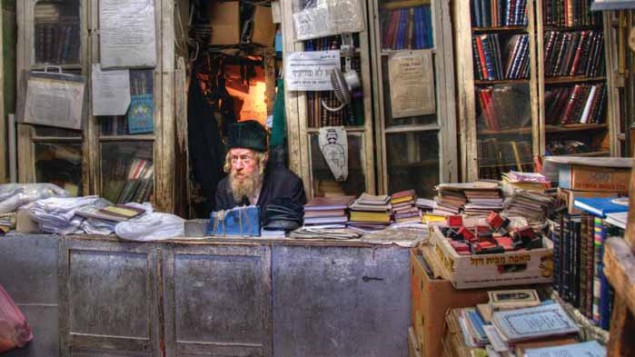

I was a yeshivah student. My chavruta Elchanan and I would study together all week, and on Fridays we would roam the streets of Meah Shearim in Jerusalem to rummage through bookstores. We would examine the new books and pick over the old ones. Once I saw a pile on the sidewalk—old tracts for sale, and next to them an old man. I scoured the pile and spied a small book whose binding was torn, and whose pages were coming apart. I looked through it and realized it was a book of sermons written by a scholar from Morocco one hundred and eighty years ago. I was overwhelmed with pity for the book. I thought to myself how hard the author had labored over his studies until he came up with novel ideas, how much of his own money he had invested in the book, how many doors he had knocked on in order to raise the balance to publish his sermons, how many doors had been closed in his face, and how happy he had been when he had finally seen the sermons printed in his book. And when it finally came out in print, who knows to how many scholars and possible patrons he had sent a copy. Probably only a few of them responded, while others did not even acknowledge receipt of the book. And of those who did respond, some sent him a miniscule sum and some got by with a few words of praise. Now this book is cast on the sidewalk of the streets of Jerusalem, forlorn and abandoned.

I asked the old man how much it cost. He picked it up, turned it over in his hands, looked at the book, looked at me and looked again at the book, trying to imagine what in the world I found in this work so that he could peg its price. Finally, he specified a rather high sum. I said to myself that this author’s derashot are worth the price that I would have to pay.

On Shabbat I picked up the book and looked through it. I saw that it was filled with well-worn ideas and that there was nothing new in it. Some of the things were nothing more than acrostics and gematria. I was about to regret that I had bought it, and that I had paid so much for it. After all, the little bit I had saved was the fruit of my hard-won efforts giving private Talmud lessons to the sons of the wealthy. But suddenly my eyes caught sight of a derashah on Parashat Vayeshev about Joseph and Potiphar’s wife in Bereishit, chapter 39. I read the author’s explanation of what the Sages had written centuries ago about the verse describing Joseph who was employed by Potiphar, and who “entered his house to do his work.” Joseph was on the verge of succumbing to the enticements of Potiphar’s wife, when he saw, say the Sages, the image of his father, Jacob. The author’s explanation of “the image of his father” found favor in my eyes. I was very pleased with the derashah the author had written on that chapter in Bereshit and the way he had explained the words of the Sages. I tucked it away in the back of my mind.

Twenty-five years later found me teaching in a yeshivah. During the winter I was invited to give a talk in the Negev on the weekly Torah reading to the members of the kibbutzim in the south. I arrived toward evening. Hundreds of people were there; the hall was already full. Standing room only. I was impressed with the love of Torah this must reflect. Before I began, one elderly woman came and told me that since she had left home fifty years earlier, she had not heard a talk on the weekly parashah.

I stood on a stage to speak, and I felt all eyes on me. I knew the audience members were thinking, let’s see what this guy has to tell us. I was apprehensive.

It was the weekly reading about Joseph and his brothers. When I got to the matter of Joseph and the wife of Potiphar and her putting Joseph to the test, I related what the Sages had said about the verse, describing Joseph who entered Potiphar’s house “to do his work.” While I was explicating the matter, one kibbutz member got to his feet and shouted excitedly, “Esteemed Rabbi, I don’t believe what you are saying, and I don’t believe what the Sages say. It is impossible that at such a moment what Joseph saw was the image of his father!” He continued making cynical remarks, saying things I don’t want to repeat here. The audience looked at him, and looked at me, and I stood there speechless. What could I say in support of the Sages’ explanation? I stood there dumbfounded for a moment, and said a little prayer in my heart, asking not to stumble, and asking the good Lord to give me some insight to save the honor of the Torah and the honor of the Sages, may they rest in peace. There I was praying, while a suspenseful silence engulfed the hall, with the audience members waiting to see how I would climb out of this corner. While that kibbutznik was standing me down, the sermon from the little book by the scholar of Morocco that I had bought once on a Friday twenty-five years earlier came to mind and whispered to me, “Everything has its time and place. Now, my time has arrived. Open your lips and elucidate the matter, and I will be with you.”

I began to explain. In the home of our patriarch Jacob in the land of Canaan there were no mirrors, and certainly men did not gaze upon their own images. Therefore Joseph the Righteous had never seen his own face. Furthermore, the Sages interpreted the verse describing the child Joseph as “the son of Jacob’s old age . . .” to mean that Joseph looked much like his father, except that young Joseph was beardless, of course. But during the years in Egypt Joseph’s beard grew in thick, and then he looked like his father in every way.

Now that evil seductress, Potiphar’s wife, most certainly had more than one mirror in her boudoir in which to primp. When she enticed Joseph, he almost succumbed to sin. As he entered her room there was a mirror opposite him. He saw in front of him an image reflected in the mirror. Joseph, who had never seen his own face, saw an image and was unnerved.

“Father, what are you doing here?” he said to himself and immediately recoiled from her. In fact, it was his own face he was seeing, not his father’s. But he did not realize that.

How wise are the words of our Sages who said that when Joseph saw the face of his father, he turned away from sin.

As I was concluding my rejoinder, the kibbutznik who had been standing menacingly opposite me shouted, “Bravo! Bravo Rabbi!” When he calmed down, he returned to his seat.

Members of the audience smiled. I continued and expounded on what the Sages were trying to convey to us in this midrash. If a person sees in his own face the image of his father and the faces of those earlier generations of his family, then this may well prevent him from sinning.

How well our Sages understood human nature.

“Bravo!,” which originally appeared in Hebrew in the Israeli paper Mekor Rishon, was translated into English for Jewish Action. Rabbi Haim Sabato co-founded the hesder yeshivah Birkat Moshe, in Maale Adumim. His latest novel is From the Four Winds (Jerusalem, 2009).