Data-Driven Decision Making: A Communal Imperative

As our society—and our community—becomes ever more complex, the need for objective, fact-based decision making is increasingly becoming a communal imperative. No longer can we rely on instinct or assumption. Like any well-managed company or institution, our decisions require data and sophisticated analysis. The OU has taken some major steps in this direction. Various of our major program arms—including NCSY, Yachad, OU-JLIC and Israel Free Spirit, the OU’s Birthright Israel program—maintain well-developed databases that assist with program development and program review. Each of our programs has, for the past four years, developed objective metrics to measure its success or failure; each is evaluated twice annually against these metrics. In short, we have moved from “management by anecdote” to a far greater reliance on obtaining and utilizing sophisticated data gathering techniques and analysis to determine how, and where, to best deploy our limited resources. But it is still not sufficient—not for us, and not for our complicated and ever-evolving community. We need to better utilize the most rigorous research and data analytics available to inform our judgements about how our community thinks and acts so that we can guide our program and policy choices.

As our society—and our community—becomes ever more complex, the need for objective, fact-based decision making is increasingly becoming a communal imperative. No longer can we rely on instinct or assumption. Like any well-managed company or institution, our decisions require data and sophisticated analysis. The OU has taken some major steps in this direction. Various of our major program arms—including NCSY, Yachad, OU-JLIC and Israel Free Spirit, the OU’s Birthright Israel program—maintain well-developed databases that assist with program development and program review. Each of our programs has, for the past four years, developed objective metrics to measure its success or failure; each is evaluated twice annually against these metrics. In short, we have moved from “management by anecdote” to a far greater reliance on obtaining and utilizing sophisticated data gathering techniques and analysis to determine how, and where, to best deploy our limited resources. But it is still not sufficient—not for us, and not for our complicated and ever-evolving community. We need to better utilize the most rigorous research and data analytics available to inform our judgements about how our community thinks and acts so that we can guide our program and policy choices.

We are, therefore, enormously excited to announce the creation of the OU Center for Communal Research, and welcome its new director, Matt Williams.

The Center for Communal Research will advance the OU’s mission to better understand and serve the Jewish community by developing a high-quality base of data, knowledge and insights about our community through a carefully conceived and executed research agenda. The Center will be the central address for all OU research and evaluation projects. It will study how people learn how to live Jewish lives; how day school graduates and college students relate to God and Orthodoxy; how our community members feel about a multitude of issues facing them, and the ways in which institutions have made—and can make—an impression on their identities; as well as the opportunities and challenges facing our community.

We anticipate that the Center’s research will form the basis for published research and symposia on selected issues of communal concern. In addition to its external research agenda that will study the larger American Jewish community, with an emphasis on Orthodoxy, the Center will also focus on internal program evaluation, which will assist in the strategic development and enhancement of OU departments and programs.

Matt Williams, the founding director of the OU Center for Communal Research, joins the OU after serving as the managing director of the Berman Jewish Policy Archive, where he conducted an array of research projects, developed strategic plans, and guided the design, execution, and evaluation of programs for a variety of Jewish and non-Jewish institutions. Matt holds degrees in art history, English, and Jewish studies from Yeshiva University, a master’s degree in history and public policy, and is currently completing doctorates in education and history, all from Stanford University. He is an alumnus of the Wexner Graduate Fellowship and a former Jim Joseph fellow in Jewish education. He was a summer fellow at the Katz Institute for Advanced Judaic Study, a Mellon Initiative Scholar of Art History at Yale University, and a visiting researcher at New York University where he taught in the Wagner Graduate School of Public Service.

One of the tasks of the OU Center for Communal Research will be to explore the likelihood that Orthodox Jews will constitute the majority of American Jewry before the end of the century—and the potential consequences of this probability.

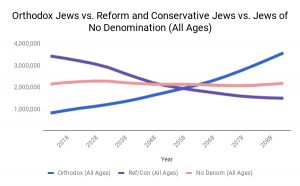

According to leading demographers, the American Jewish landscape will undergo a seismic shift over the next fifty to seventy years. Orthodox Jews, who currently represent approximately 10 to 12 percent of the American Jewish population will—if current projections hold—become the majority of American Jewry. “There will be more Orthodox than Reform and Conservative [Jews] combined within about 40 years. And before the end of this century the Orthodox will outnumber all other American Jews combined, including those who belong to no denomination.” (See the Forward’s “Orthodox to Dominate American Jewry in Coming Decades As Population Booms,” by Ari Feldman and Laura E. Adkins, June 12, 2018, http://forward.com/news/402663/orthodox-will-dominate-american-jewry-in-coming-decades-as-population/.)

The data, say the experts, is compelling and inexorable. The non-Orthodox population marries later and has fewer children—less than two per couple, or a negative rate of replacement. In contrast, the birthrate among Orthodox Jews is over four children per household. Add to this demographic reality the well-documented, dual effects of assimilation and intermarriage on population trends; and project out several decades . . . the projections are hardly far-fetched. If anything, their effects may become manifest far sooner than predicted. To be sure, the demographic predictions are just that, predictions . . . based on a myriad of assumptions regarding the continuation of current observable trends. They require careful analysis and reflection, including consideration of the impact of aliyah; inward and outward movement from and into Orthodoxy; the effect of economic trends on family size; patterns of marriage and divorce; and a myriad of other factors. But the demographic trends within the Jewish community seem clear: our community is growing—rapidly; and the non-Orthodox population is shrinking.

The prospect of demographic ascension raises new and profound questions about the future of Orthodox life in America; the nature and responsibility of our institutions; and the relationship between Orthodoxy and the broader Jewish community and American society generally. Some of these challenges we do not yet have the capacity to imagine, let alone the infrastructure to resolve. The questions abound: how will we serve the needs of a community that may be, at once, among the poorest and the wealthiest, in America? What will the communal dynamics of marriage look like decades hence? Will our communal infrastructure be capable of providing appropriate support and services to an ever-growing population of singles? How many children will be reared in two-income households? How will this affect educational success and lifestyle choices? How will we relate to the broader American Jewish community that is, increasingly, becoming interfaith in composition and straying further and further from religious affiliation? How will changes in our political ideology manifest themselves, and impact upon— perhaps even transform—our sense of communal identity? What are the strategic consequences of further Progressive alienation from support for Israel—on our community and on historical bipartisan support?

In short, must we begin to plan now for a future Jewish America in which the fate of American Jewry will increasingly rest on our shoulders. And, if so, what must that planning process look like?

Here is a random sample of the types of issues that we will face and need to plan for. I have selected but a few of the myriad potential examples to illustrate the magnitude and complexity of the task before us:

1. Our Expanded Obligation for Outreach

As Rabbi Dr. Abraham Unger has written recently: “Save for a small Orthodox minority numbering not much more than 10 percent of US Jewry, American Jews have overwhelmingly decided not to marry each other and commit their children to serious Jewish education or communal commitment. With more than 70 percent of American Jews marrying non-Jews, according to the most current Pew Research Center Survey of US Jews, and the minority of non-Orthodox Jews who do marry Jewish partners not providing substantive and consistent Jewish exposure to their children, it is hard to see how American Judaism will survive in any meaningful way outside of Orthodoxy.”

We are left with two stark choices: We can let history take its brutal course, or we can double—and double again and again—the efforts we make to bring an energized, uplifting, passionate—and informed—Yiddishkeit to hundreds of thousands of our Jewish brethren. The kiruv movement must be embraced, reinvigorated and supported with the funds and talent required. It is a fundamental imperative of a minority on its way to majority status. How will we plan to meet this imperative? Indeed, what does this imperative look like to an increasingly interfaith Jewish community?

2. Numbers Matter—Will American Jews Maintain their Important Place in the Public Square?

How will we adapt to a smaller, albeit a far more religiously committed, population base, particularly one likely to be concentrated in a relatively small number of urban hubs? What will be the impact be on our political clout? And, derivatively, what will the consequences be for the long-held tradition of bi-partisan support for Israel (and its national security and defense) as the Orthodox community tilts further to the right of the political spectrum. A challenge of future majority status that will require provocative analysis.

3. The Relationship Between Diaspora and Israel

How will the Orthodox community—particularly as it reaches, or nears majority status— maintain a broad-based consensus on identification with, and support for, the State of Israel? Will our community, particularly if no longer a minority, feel more confident and secure—and hence more willing to tolerate the expression of heterodox viewpoints, particularly among a younger generation increasingly alienated from the Jewish State and the Zionist agenda? Or will the opposite be the case, with majority status seen as a vindication of the ascendance of Torah values and proof of their eternal message? In short, how will the community of ma’aminim bnei ma’aminim relate to and interact with the remaining community of American Jews who continue to identify with Jewish culture and peoplehood, but not with its religious essence. Is there a place for liberalism within the Orthodox community? How will we maintain civil discourse, and civil disagreement, in an increasingly polarized community?

These questions—and scores like them—animate our thinking as we launch our new OU Center for Communal Research. We urge our readers to react to this essay by writing to me (afagin@ou.org) or to Matt Williams with comments and/or suggestions for vital research projects that would benefit our community and enhance our ability to plan for the future. May we see great success in our collective avodat hakodesh as we continue to identify—and help respond to—the needs of Klal Yisrael.

Allen I. Fagin is executive vice president of the OU.

Meet Matt Williams

Meet Matt Williams

JA: Can you tell me a little about yourself?

I was born in Oklahoma and grew up in Georgia. I’m a member of the Choctaw Nation and a Sephardic Jew whose father emigrated from Morocco. I’m probably the first American Indian, Sephardic Jew the OU has hired in its history. In some ways, I think this represents the dynamic demographics of the American Orthodox community, once almost exclusively from Eastern Europe. That “outsider” perspective is probably an asset to a researcher, but as the OU has signaled with my hiring, on some level, there really shouldn’t be “outsiders” among those who want to participate in Jewish life.

JA: Why did you decide to become a social scientist and dedicate yourself to studying the Jewish community?

I’ve always been passionately curious about Judaism. I triple majored at Yeshiva University in art history, English and Jewish studies. I prepared to pursue semichah but instead earned a Mellon Initiative Fellowship at Yale University. Subsequently, I was named a YU Point of Light and granted the Yeshiva College Honors Program Award for Distinguished Student.

I’m driven by questions—how does one learn how to be Jewish? How does that express itself within, alongside, and juxtaposed with institutional Jewish life? And how do we in the Jewish establishment implicitly limit the types of ways individuals can enter and engage with the Jewish community?

JA: Why are you interested in this particular role at the OU?

I’m thrilled to help the OU’s various departments better understand what they do and gauge their actual impact. But more than that, this position allows me think more broadly, and build a research agenda that can help us address and maybe even solve challenges in the broader community. It speaks so well of the OU that its leaders decided to invest in research and see it as essential to our work.

JA: What areas within the Orthodox Jewish world are you excited about studying?

One area is the economics of Jewish life—affordability, whether it’s a function of tuition or housing or healthcare—it’s something we need to get a better handle on. A second area is the evolving gender roles of our community. I don’t mean the growth of women’s spiritual leadership per say, but the suspected increase in two-income households, the later-marriage phenomenon and the sheer number of singles affected by the shidduch crisis. And a third is how do we, as Orthodox Jews, relate to the broader American Jewish community? We need to better understand these phenomena before we can thoughtfully approach any of them.