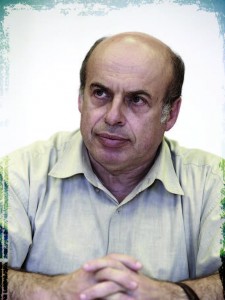

A Conversation with Natan Sharansky

on the situation of the Jews in Europe

By Elli Wohlgelernter

A former refusenik who previously served in the Knesset and as a minister in the Israeli government, Sharansky has been chairman of the Jewish Agency for Israel since 2009.

A conversation with Natan Sharansky on the situation for Jews living in Europe is nothing less than a wide-ranging tutorial on politics, democracy, philosophy, government and history. And because he’s a student of history and societies, Sharansky is very worried about the reality facing not only the Jews of Europe, but Europe itself. It is a continent, he says, that is rushing to embrace the philosophy of John Lennon:

Imagine there’s no countries

It isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too

Sharansky says it straight out: If Europeans have nothing to die for, nothing worth fighting for, then they are doomed.

He is not worried about the survival of the Jews of Europe, he says, because they will be the first to leave. And it’s already happening. For the first time since 1948, more Jews came to Israel in 2014 from open societies than from distressed countries, a historic turning point in the annals of aliyah.

The immigration was led by France, with 7,000 arriving in 2014, more than double the number in 2013. Ironically, Jewish Action spoke with Sharansky three days before the terrorist attack on the French magazine Charlie Hebdo, and five days before the attack on the Hyper Cacher kosher supermarket in Paris. Sharansky’s prediction for 10,000 olim from France in 2015 can thus be considered a conservative estimate.

Elli Wohlgelernter: What is your overall assessment of the situation for Jews living in Europe?

Natan Sharansky: Today, in the center of Europe, for the Jewish community to feel that they are almost besieged, that outside of the synagogue they should not show that they are Jewish, that is a very unusual feeling—to be a proud European and, at the same time, to be scared. That is something new.

EW: Is the increased aliyah from France because of the shooting at a Jewish school in Toulouse in March 2012?

NS: No, no. Twelve years ago, during the Second Intifada, the chief rabbi of Paris and the heads of the [Jewish day] schools told the youths, “Don’t wear your kippahs in public.” It was never taken back. So a whole generation has already grown up with the feeling that in the streets of your hometown, you have to hide.

EW: How did Europe get to this point?

NS: The traditional classical European ideal is the national democratic state. The idea was born with the French Revolution and, to some extent, the American Revolution. And it was very closely connected to the idea of liberalism. Why? Because in order to guarantee the rights of every individual, human rights, the rule of majority, you must have this majority which is linked by some very deep mutual background. There must be some glue that is keeping this together and this glue is their identity, whether it is based on religion, nationalism, history or the value of their culture. It went together.

This idea that everything is relative, and you should not fight for anything, means that Europe will not be ready, and is not ready, to fight for its own values.

The situation changed radically after the Second World War. We had centuries of religious wars, and then we had two awful nationalistic wars, and tens of millions were killed for nothing. Then the understanding was that identity [and religion] is a bad thing, nationalism an awful thing. That’s why I mention John Lennon: Let’s imagine a world where there is no religion, no nation, no God, and where there is nothing to die for.

This idea of creating a universe without identities, life without meaning, is very decadent, very dangerous. It takes away the meaning of life. I wrote about it many times in my books. Every person has two deep, basic desires: to be free and to belong. And the real full, meaningful life is when these two things come together. But postnational, postmodern and multicultural Europe says two things: [First,] postmodernism says that we should understand that our nationalism is not important; in fact, it is a negative thing. [Second,] postmodernism and multiculturalism say that all cultures are relative; there is no absolute value. So the culture that is not based on human rights has absolutely the same value as a culture that is based on human rights. So they say, “These people to whom you give citizenship, who are we to demand that they give away their principles for the sake of ours?” So suddenly they are permitting a large number of people to become citizens, without insisting that they accept all the principles of liberal society. This idea that everything is relative, and you should not fight for anything, means that Europe will not be ready, and is not ready, to fight for its own values.

EW: How does all that impact the Jews of Europe?

NS: Those Jews who don’t want Judaism will assimilate, and be washed out of Jewish history. But for those who want to be part of Jewish history, Israel is very important. But the world of liberal Europe—which we Jews helped build—hates Israel. You go to work and your colleague says, “You’re a great guy, but you can’t feel solidarity with this awful state.” So it’s very uncomfortable, and it’s not simply anti-Semitism.

There is also a world of classical, conservative religious Europe, like Le Pen Europe, let’s say, that at this moment doesn’t look anti-Semitic, but historically Jews know they always looked at us as “the other.” They accepted us, but not as part of their European culture.

So either you live in a society that hates Jews, or you live in a society that hates Israel. And you don’t want to be there. But that’s a problem that’s much bigger than a problem for Jews. Like many times in history, Jews are the harbinger of what’s really happening.

EW: The Chareidi Jews of Europe, and all those who are visibly Jewish—is their predicament even worse?

NS: Look, what does it mean it’s worse? I believe there are two anchors that keep people Jewish: faith and Zionism, meaning Judaism and Israel. If you have both of them, great. If you have at least one of them, there is a great chance that you will remain a Jew. If you don’t have either of them, you will assimilate fairly quickly. So from this point of view, the Antwerp community, the Chareidi community, will survive. There is almost no assimilation in that community. So in terms of Jewish continuity, I think they’re in less danger. In terms of physical survival, they are in danger.

EW: There has been a backlash in Europe, rallies taking place in cities like Dresden. Can the surrender of Europe be stopped?

NS: I think if it will be stopped, it will not be because of sympathy to Jews. I hope it will be stopped because Europe starts recognizing that nonresistance to this invasion of anti-liberal values threatens the whole society of Europe. Either Europe will continue to pretend that there is nothing to fight for, and therefore will not fight, and then it is doomed; there is no future for European civilization. (Of course, then there will be no future for the Jews in Europe, and the Jews will be the first to leave.) Or at some point, Europe will realize that there is something to fight for. If this happens, then there is a chance.

EW: Do you believe it will happen?

NS: I don’t know. My personal responsibility is to make sure that any Jew who feels uncomfortable in Europe will feel comfortable in Israel. Time is running out.

Veteran journalist Elli Wohlgelernter is the diplomatic and political correspondent for IBA-TV in Jerusalem, where he has lived since making aliyah in 1991.