Creative for a Cause

Project Driveway volunteer delivering groceries to those homebound due to the Covid-19 threat. Courtesy of Eyal Arkin

How innovation and chesed defined the Jewish community’s response to Covid-19

When Covid-19 began to spread rapidly in the New York area in March, families watched helplessly as loved ones were whisked away, unaccompanied, in ambulances. Because of the highly contagious nature of the virus, hospitals prohibited all visitors. Families were frantically trying to reach their relatives, many of them elderly.

A group of Chassidim in Brooklyn felt compelled to help. “Very sick people were all alone, and their families had no idea what was going on,” says Moshe Teitelbaum, a member of the group. Their solution was WellTab, thousands of tablet computers loaded with a custom-designed videoconferencing platform. As of this writing in May, tablets were distributed free of charge to more than 1,800 hospitalized patients, with a corresponding tablet for their families at home.

The software and hardware challenges that had to be overcome were formidable.

“We needed a plug-and-play controlled by the family—but also with a privacy mode on the patient’s end,” explains Teitelbaum, who has telecom experience as the founder of the B2B payment processing company shtar.com.

The group designed the tablets with a unique platform that doesn’t time out, to make sure nurses wouldn’t have the increased burden of having to help patients log back in. “Unfortunately, these patients are mostly immobile,” says Teitelbaum.

Furthermore, to ensure ease of use, every device had to be compatible with the Wi-Fi networks of all hospitals in the region, so they would immediately work wherever they ended up. “It took fifty guys working on this,” Teitelbaum explains. “They had to register the devices on all the networks. They were literally going “from hospital to hospital”—sitting outside, of course.

WellTab volunteers connect tablets to Wi-Fi outside of Mount Sinai Hospital on New York’s Upper East Side. Courtesy of Moshe Teitelbaum

Tablets were distributed to patients at Weill Cornell Medical System, Columbia University Medical Center, NYU Hospital, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Lenox Hill Hospital and Mount Sinai Hospital. Within a few short weeks, WellTab became a full-time operation, with more than sixty volunteers and three paid employees. Network technicians and around-the-clock tech support for families kept the program running smoothly. Through a partnership with Hatzalah in the New York area, ambulances were stocked with tablets; patients could be admitted to a hospital with a device in hand, without having to wait for their families to obtain and deliver one to them.

According to Teitelbaum, the gratitude of patients and families has been overwhelming. But these men felt like they were just trying to do something to help a fellow Jew during a difficult time. “I was locked in at home and felt so powerless,” Teitelbaum says simply. “At the very least, I wanted to be relevant.”

A New Kind of Kindness

On lockdown for weeks—or months—so many others in the Jewish community shared Teitelbaum’s resolve, putting in countless hours doing what they could to help others.

“We are fortunate to be a very interconnected and social community,” explains Rabbi Steven Weil, former senior managing director at the OU. “During this pandemic, everyone is isolated. This has very much sensitized us to other isolated people, and we can empathize to a greater degree with what others are experiencing.” He believes that this simple fact motivated individuals to spring into action to assist their neighbors.

Almost overnight, programs appeared to address issues that hadn’t existed before. These innovative efforts—including programs to assist the unemployed, the elderly and the isolated, among so many others—harnessed technological skills, social-media savvy, or just hours of sheer manpower. Every one of these initiatives sent a singular message to fellow Jews: You are not alone.

“Unfortunately, we all feel the pain of Covid-19,” says Rabbi Weil. “Communities where Jews live have been hard-hit—whether or not we’ve personally lost loved ones or jobs. In general, the closer you are to pain, the easier it is to give.”

A Double Chesed

Like many small business owners, the beginning of the pandemic brought uncertainty and stress for Josh Katz. The owner of Ben Yehuda Pizza in Silver Spring, Maryland, he saw Purim orders canceled and knew the worst was yet to come: one-third of his business comes from schools and shuls—which were suddenly closing indefinitely.

“It was a low point,” he recalls. “We didn’t know what to expect, and the rules were changing every two days. Can we stay open and pay people? Do we close our doors? No one knew.” Josh had to dramatically reduce employees’ hours, and he took a pay cut himself. “The restaurant is the primary parnassah for my family,” he adds. “It’s been very tough personally as well.”

Then, one day, local resident Bethany Mandel called Ben Yehuda Pizza and ordered twenty pies to be delivered to the healthcare workers at a nearby hospital. That call was the beginning of Kosher19, an organization Mandel co-founded to deliver food to frontline healthcare workers during the pandemic.

Mandel tweeted the idea of sending kosher food to hospital staff. Within twelve hours, she had raised $10,000 for the cause. She joined forces with fellow Silver Spring resident Dave Weinberg and Long Island-based Dani Klein of Yeahthatskosher.com. “We formed a board and found a lawyer,” explains Weinberg. “Pretty much overnight we created a nonprofit organization.”

The Orthodox community is built for a time like this. We’ve been raised, hopefully trained, for this occasion.

The three agreed on the primary goals for their project. “We would deliver kosher food to the staff of entire units (and not exclusively to those who keep kosher),” says Weinberg, “while keeping kosher food businesses going during tough times. We also hoped to generate some good press for the Jewish community.”

When Mandel called Ben Yehuda Pizza with that first order in March, Katz offered wholesale pricing to support her worthy cause. “She responded, ‘We are happy to have a discount, but we also want you to have revenue,’” Katz recalls. “It was incredibly generous of Kosher19. My staff was touched. I was touched. It was a nice surprise at a time when we were getting bad surprises left and right.”

Ongoing orders from Kosher19 was “a huge relief” for Katz. “The rug had been pulled out from under us,” he says. “Suddenly, we started to feel like maybe we could make it through this thing.”

In just six weeks, at the height of the pandemic in the US, Kosher19 sent meals to more than two hundred medical units at hospitals around the country, from Maryland to Missouri, New Jersey, and Florida. During that time, the organization raised more than $85,000.

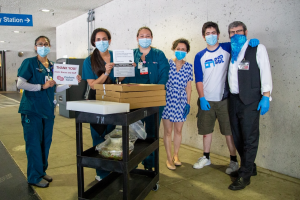

Kosher19 volunteers drop off food to nurses at Cedars Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, California. Courtesy of Dave Weinberg

For medical workers on the frontlines of the pandemic, the delivery of food from local kosher restaurants like Ben Yehuda Pizza was a welcome diversion during long, exhausting shifts. “It was incredibly stressful at the hospital as the pandemic started to pick up,” recalls Dr. Steve Singer, a physician in the Emergency Department at Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring. “People were coming in very, very sick. There were so many questions about how to treat the patients, and it felt like things were changing on a daily basis. Everyone was constantly on edge.”

Finding time to eat was rarely a priority in that high-pressure environment, explains Dr. Singer. The hospital staff truly appreciated the meals that were sent as much as the sentiment behind them. “It’s such a comforting feeling to know that the community recognized what we were doing and how hard we were working,” he says. “For those of us who keep kosher, it was even more meaningful. It was a tremendous help, both food-wise and emotionally.”

From Dr. Singer’s perspective, there was an added bonus to Kosher19’s gesture of goodwill: “It shone a nice spotlight on the Jewish community near the hospital.”

Heroes in High School

Because of her age and susceptibility to respiratory infections, retiree Joni Schockett was considered at high risk for Covid-19. She and her husband Michael found countless ways to keep busy, but they were confined to the four walls of their Needham, Massachusetts home.

“East Massachusetts was especially hard hit, and my doctor’s PA advised me to stay home and not shop or go places if at all possible,” says Schockett. Her husband, too, was told to stay home.

Though they had never met, it was with individuals like the Schocketts in mind that Eyal Arkin, David Carmel and Anat Katz decided to create Project Driveway, a grocery-shopping and delivery service in the Boston suburbs. At the height of the crisis, their operation had about thirty-five volunteers buying and delivering groceries for their neighbors, mostly the elderly, in the Boston area. Another fifteen volunteers worked behind the scenes, keeping the organization running. Especially noteworthy is the fact that every person involved was a high school or college student.

When the project launched at the beginning of April, the teens were filling about thirty orders a day. While many pop-up grocery delivery services required electronic payments from clients, Project Driveway aimed to be more accessible. “Not everyone we served has Venmo or PayPal,” explains Arkin, who is seventeen and a senior at Brookline High School. “In fact, the majority probably did not. We set up a finance system to accept credit cards, which was especially important since we wanted to avoid using cash or checks to prevent potential spread of the virus.”

Arkin and his cofounders, who are involved with NCSY (primarily through JSU at their public high schools), turned to Rabbi Yudi Riesel, director of Greater Boston NCSY, for help getting their credit card system up and running and with any other issues that arose. “Rabbi Riesel has been incredibly helpful,” says Arkin. “He served as a mentor for us.”

“I’m blown away by how much time the teens put into this,” says Rabbi Riesel. “Countless hours were spent on web site creation, monitoring orders, shopping, deliveries, managing payments. They didn’t just come up with a nice idea and let it fizzle out.”

“As an educator, I usually find myself in the position of providing inspiration for our teen base,” says Rabbi Riesel, “but there’s no greater inspiration than seeing teens step up for the community.”

Though Project Driveway was not focused specifically on the Jewish community, the volunteers made every effort to meet the unique needs of the large Jewish population in the area. “People knew they could rely on us to make sure the items were kosher,” says Arkin. “We were sensitive about delivering before Shabbat if that’s what people wanted. Not all of our volunteers keep kosher, so we created a kosher order form and we made sure people who are familiar with kosher handled those orders.”

Schockett appreciated this aspect of Project Driveway’s assistance, as she had encountered issues with other grocery services, no matter how detailed she tried to be about kosher symbols. “They were buying me non-kosher things that I was stuck with,” she says. “When I ordered [through Project Driveway] before Pesach, they knew what gefilte fish was!”

Project Driveway’s volunteers also offered services beyond groceries. They picked up prescriptions for clients and stopped off at the local hardware store. “I sent an e-mail asking if they’d go to the garden store for me,” says Schockett. “I told them they could say no, but Eyal just went and did it!”

Pleased with the help she received, Schockett offered to pay for her deliveries, or at least give a tip. Arkin insisted that they would not accept any payment. “He said they were just doing a mitzvah,” she recalls. “They did take donations to cover expenses, and they told me it also covers the cost of the food they delivered to some clients who couldn’t pay for their groceries.

“These are just kids,” she says incredulously, “but they have such grace. They did this without making anyone feel beholden. No questions asked. It’s remarkable.”

A Light in the Darkness

WellTab, Kosher19 and Project Driveway are just three examples of the myriad creative programs that were launched to help those in need during these difficult months. In fact, Rabbi Weil feels that the pandemic has served as a litmus test for the strength of the community and its values.

“If we weren’t taking care of our fellow Jews in times like these,” he posits, “then what is all the time, education and money we’ve put into our organizations and institutions for? The Orthodox community is built for a time like this. We’ve been raised, hopefully trained, for this occasion.”

To Rabbi Weil, hundreds of examples from every Jewish community across the US indicate that, as a whole, Klal Yisrael has come through for each other. “In my point of view,” he says, “we have truly stepped up to the plate.”

While the worst of the pandemic has hopefully passed, those who threw themselves wholeheartedly into chesed projects aren’t yet hanging up their hats. Teitelbaum expects the need for WellTab to continue as long as any hospital units restrict visitors. For its part, Kosher19 is prepared to serve up more meals to healthcare workers should there be, God forbid, a second wave of Covid-19, as many predict.

And Arkin anticipates that Project Driveway will continue to be relevant for a while. “Even after the pandemic has passed,” he explains, “there will still be fear, especially for the people we serve. These are vulnerable people who may continue to stay home.”

Whether these initiatives end up having staying power is beside the point. For those who benefited from the chesed, the tremendous amount of time and effort put in was unquestionably worthwhile.

“It’s been a very dark time,” says Schockett. “[Covid-19] has hit us so hard. And then these kids come along . . . and suddenly, it’s conceivable that there is sunshine at the end of this.”

Rachel Schwartzberg works as a writer and editor and lives with her family in Memphis, Tennessee.

More in This Section:

Lessons from the Pandemic: Part II in a series on how the virus has affected our lives