Brown V. Board of Education: An Orthodox Cause?

Children on the first day of desegregation in Fort Myer Elementary School in Fort Myer, Va,. in September, 1954. Photo: Corbis

Sixty years after Brown v. Board of Education, remembering Orthodox Jewry and the Civil Rights Movement

In December 1958, Rabbi Isadore Goodman of Memphis traveled up to Indianapolis to help celebrate the dedication of a new Orthodox synagogue building. In his remarks, the Southern rabbi spoke about Orthodox Jewry’s role in the raging Civil Rights Movement. His recommendation: they should not participate. Jews, Rabbi Goodman explained, “become more vulnerable when they dissipate their strength in other movements.”1 Rabbi Goodman recognized the weight of his words, especially coming from a Southern clergyman. He therefore stressed that he was not a racist and sympathized with “equalitarian movements.” Rabbi Goodman just did not believe that Orthodox Judaism was in a position to help.

One historian surmised that Rabbi Goodman’s view was “typical of Orthodox Jews.”2 Certainly, Orthodoxy did not boast a freedom fighter like Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel of the Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative). Similarly, the Rabbinical Council of America did not offer the kind of financial and political support like the Central Conference of American Rabbis (Reform). However, leading exponents of Orthodox Judaism did, in fact, speak up.

A 1968 shul bulletin with a eulogy for Martin Luther King on the front page. The bulletin is from Congregation B’nai Torah of Philadelphia, an Orthodox shul.

Rabbis Bernard Drachman, Leo Jung, Ahron Soloveichik and Pinchas Teitz all used their rhetorical powers to speak out for African-Americans. These leaders rooted their politics in Biblical language. For example, Rabbi Jung compared Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Moses while Rabbi Teitz envisaged desegregation to the “breaking down of the walls of Jericho.”3 Other congregational leaders marched in the Selma demonstration in 1962. Their courage to participate was promptly recognized by African-American leaders.4

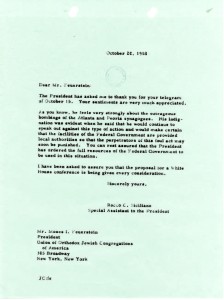

Rabbinic elites were not the only ones who got involved. The National Council of Young Israel and the Orthodox Union passed resolutions that sought to mobilize their Orthodox constituencies. In the wake of race riots throughout the South, OU President Moses Feuerstein worked together with the American Jewish Congress in 1958 to pressure President Dwight Eisenhower to convene a conference that would “stress upon the uncommitted peoples of this globe the freedom, the equality and tolerance prevailing in the United States of America.”5 Some years later, the OU established a special committee to enable Orthodox Jews to better partner with African-American civil rights advocates.6

Young people played their parts as well. In 1940, Yeshiva College (which subsequently became Yeshiva University) students wrote approvingly of a formation of a “Committee to End the Ban on Negroes in Major League Baseball.” The young men charged that fans “have not received a fair return for their money” and dreamed of a time when they might see Negro League stars like Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige compete against major league legends such as Hank Greenberg and Joe DiMaggio. “Yet, men of this caliber,” Yeshiva collegians lamented, “are barred from active participation in organized baseball because their skin is of a darker hue.”7

Rabbis Bernard Drachman, Leo Jung, Ahron Soloveichik and Pinchas Teitz all used their rhetorical powers to speak out for African-Americans.

In April 1960, Yeshiva students traveled to Greensboro, North Carolina, to stand with other protestors against racial bigotry. They saw their mission in religious terms: “As Jews we have a moral and religious duty to uphold the rights of our fellow man,” the students preached. “As Jews we must be in the vanguard of any movement which seeks to break the bars of discrimination.”8

Rabbi Emanuel Rackman, who served as vice president of YU and president of the RCA and held pulpit positions at distinguished New York congregations, was a key figure in getting the Orthodox community involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Photo: Yeshiva University Archives, Public Relations Records

Notwithstanding these efforts, no one within the Orthodox camp formulated a position similar to Protestant advocates and Reform Jewish leaders. The closest was Rabbi Emanuel Rackman. For many within the Orthodox community, Rabbi Rackman was its “central figure” during the twentieth century.9 For others, due mostly to his liberal interpretation of Jewish law, Rabbi Rackman was the ultimate “gadfly.”10

In any case, Rabbi Rackman was an institutional force within American Orthodoxy. He served as vice president of YU and president of the RCA, and held pulpit positions at distinguished New York congregations. In 1948, he wrote about the “dastardly fashion in which Southern states have subverted the language and intent of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments.”11 From his pulpit five years later, Rabbi Rackman wondered aloud whether whites and Blacks could ever “sit as brothers, even in the pews, to listen to the Sermon on the Mount.”12 In a sermon delivered in 1958, Rabbi Rackman linked the oppression felt by Blacks and Jews at the hands of white fraternal social lodges. “It is well known that in all of these fraternal orders there is an appalling lack of brotherhood,” lamented Rabbi Rackman. “Often, Jews and Negroes must organize lodges of their own.”13

But Rabbi Rackman was not just about rhetoric. He was deeply concerned that other Orthodox leaders understand the stakes of American civil rights. Consequently, Rabbi Rackman took full advance of his station when the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education sixty years ago, on May 17, 1954. The court’s unanimous ruling declared de jure racial segregation illegal. At that time, Rabbi Rackman was chairman of the RCA’s Convention Committee and slated to become the organization’s president at the upcoming gathering. The July convention in Detroit was to take place just two months after the landmark court case and Rabbi Rackman sought to sensitize the 600 Orthodox rabbis and leaders to the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. A year earlier, the RCA had resolved to back school desegregation, but that was not enough for Rabbi Rackman. So he invited Maxwell M. Rabb, associate counsel to President Eisenhower, to keynote the forthcoming conference.

Yeshiva College students traveled to Greensboro, North Carolina to protest racial bigotry and addressed civil rights issues in the pages of The Commentator, the student newspaper. Photo: Yeshiva University Archives, Commentator, May 5, 1960

Rabbi Rackman asked Rabb to discuss President Eisenhower’s “approach to civil rights and social security in their broadest meanings.”14 Moreover, the rabbi hoped that Rabb’s presence might also offer Orthodox rabbinic leaders a much-needed example. “For a long time Orthodoxy was accused of failure to assimilate modernism with its point of view,” wrote Rabbi Rackman. To remedy this conception among Orthodox leaders, it was Rabbi Rackman’s hope that Rabb—the highest-ranking Jew in the Eisenhower administration—could demonstrate through his words that “the future lies with those who do not feel that America calls for the surrender of one’s religious faith and practices, but rather for greater opportunities to apply that faith and those practices more fully and more meaningfully.”15

Rabb did exactly that. He connected the “question of equality of opportunity” to the “interest to all of us who are Jews.” Rabb reminded his rabbinic audience that it was singularly the Jewish people who cannot forget “for we have known the cruel injustice through the centuries of the yellow hat and the yellow badge—of the Pale and the Ghetto—that left us segregated, marked in body and in soul.” The Brown decision reflected those values, suggested Rabb. “The whole process,” said Rabb about what he believed to be an inherently Jewish mission, “will be greatly accelerated as a result of the decision rendered just two months ago by the Supreme Court of the United States that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.”16

Rabb’s remarks were very well received by the RCA. Rabbi Rackman thanked the White House advisor for a “magnificent address” and for making himself available afterward to discuss political issues with convention attendees. “All of this,” wrote Rabbi Rackman, “made a terrific impact on the leaders of our organization.”17 Although the moment probably held a strong short-term influence, its impact probably weakened rather quickly.

Correspondence between OU President Moses Feuerstein and US President Dwight Eisenhower in 1958 about convening a conference that would “stress upon the uncommitted peoples of this globe the freedom, the equality and tolerance prevailing in the United States of America.” Courtesy of Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum

Before long, American Orthodoxy forgot about Rabbi Rackman or any other contributor to civil rights. As early as 1968, one Orthodox writer accused his community of “non-involvement” and “disquieting silence.”18 That sort of historical amnesia had much to do with the Judeo-Christian ethic that captured American culture at midcentury. By the late 1960s, many Jews no longer considered themselves an ethnic minority. In addition, this period also witnessed increased support for Israel and Soviet Jewry, causes that no doubt replaced other righteous endeavors.

In our time, the Orthodox community has reclaimed its voice in the fight for social justice.19 In particular, Orthodox students in colleges and day schools regularly volunteer to serve on activist missions in America and abroad. I recall my astonishment in 2006, as part of a 300-person YU delegation that traveled to a Save Darfur rally in Washington, D.C. To explain that return to activism, we might offer a whole new set of historical variables unrelated to the efforts of earlier Orthodox preachers and protestors. Still, we may nevertheless take stock and celebrate the work of those who labored before us.

Listen to Rabbi Zev Eleff discuss social justice and Orthodoxy at http://www.ou.org/life/community/savitsky_eleff/.

Notes

1. “Says Rabbis Shouldn’t Lead Integration Fight,” The National Jewish Post and Opinion, December 19, 1958.

2. See Clive Webb, Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights (Athens, Georgia, 2001), 170-71.

3. See Leo Jung, “The Emergence of Human Dignity,” The Jewish Center Bulletin 36 (1965): 1; and Martin Arnold, “Only 2,000 Attend Negroes’ Polo Grounds Rally,” New York Times, August 26, 1963.

4. See, for example, “Boston Rabbis Join Montgomery March,” Boston Jewish Advocate, March 25, 1965.

5. Moses I. Feuerstein to Dwight D. Eisenhower, October 15, 1958, Office of the Special Assistant to the President for Personnel Management Records, 1953-61, Box 43, FF “Civil Rights—White House Conference Proposal,” Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

6. Eugene Silkes, “A Conflict of Rights?,” Jewish Life 71 (1965). I thank Nechama Carmel and Rashel Zywica for pointing out this source.

7. “Color, Race or Creed,” The Commentator, April 10, 1940.

8. “Fight for Equality,” The Commentator, May 5, 1960.

9. See Charles S. Liebman, “Emanuel Rackman and Modern Orthodoxy,” in Studies in Halakha and Jewish Thought, ed. Moshe Beer (Ramat Gan, 1994), 23–31.

10. See David Singer, “Emanuel Rackman: Gadfly of Modern Orthodoxy,” Modern Judaism 28 (2008): 134-48.

11. Emanuel Rackman, “Legislating with Regard to Racial and Religious Discrimination,” Masmid (1948): 50.

12. Emanuel Rackman, A Modern Orthodox Life: Sermons and Columns of Rabbi Emanuel Rackman (Hoboken, New Jersey, 2008), 35.

13. Ibid, 55.

14. Some historians suggest that Eisenhower was unhappy with the Brown decision. See, for example, David A. Nichols, A Matter of Justice: Eisenhower and the Beginning of the Civil Rights Revolution (New York, 2007), 109-110.

15. Emanuel Rackman to Maxwell M. Rabb, June 22, 1954, Maxwell M. Rabb Papers, 1938-1989, Box 56, FF “Rabbinical Council of America (2),” Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library.

16. “Remarks by Mr. Maxwell M. Rabb Cabinet Operations Official and Associate Counsel to the President at the Annual Convention of the Rabbinical Council of America in Detroit, Michigan, July 20, 1954,” Box 56, FF “Rabbinical Council of America (2).”

17. Emanuel Rackman to Maxwell M. Rabb, August 2, 1954. Box 56, FF “Rabbinical Council of America (2).”

18. Bernard Weinberger, “The Negro and the (Orthodox) Jew,” Jewish Observer 5 (1968): 11-12.

19. See Dyonna Ginsburg, “Re-anchoring Universalism to Particularism: The Potential Contribution of Orthodoxy to the Pursuit of Tikkun Olam,” in The Next Generation of Modern Orthodoxy, ed. Shmuel Hain (New York, 2012), 3-22.

Rabbi Zev Eleff is a doctoral candidate at Brandeis University. He also teaches Judaic studies at Maimonides School in Brookline, Massachusetts.

Dynamite and Desegregation

The wave of dynamite attacks upon Jewish institutions in several Southern states opens a new phase in the upheavals wrought by resistance to the Supreme Court ruling on desegregation of the public schools. The attacks, it is clear, are designed not merely to intimidate Jews against aiding efforts to secure justice for the Negro. Manifesting a planned pattern, they are meant to advertise the intent of their perpetrators to go to any length to achieve their ends.

Responsible organs of Southern opinion, together with the rank and file of Southerners, have voiced their sense of burning shame and indignation at the outrages. The sincerity and force of these expressions give unmistakable assurance that the elements responsible for the outrages are abhorred by Southerners at large. It is to be hoped, therefore, that reaction to the attacks, opening the eyes of all to fatal dangers, will result in effective action. There can be no temporizing with forces of terror.

In any event, the terrorist moves will surely not deter Jews from acting as conscience and judgment dictate. No Jew can rest easy while the belief that all men are children of one Father is mocked, while the concept that all men are created equal is violated, while the Supreme Court and the Constitution of the United States are defiled. All men of good will must extend to the South the fullest measure of understanding in its painful problem of adjustment to a change in the pattern upon which Southern society has been based for generations. But there lies at stake more than the Southern pattern of life, and more even than the rights of Negroes. A great moral principle, the very foundation stone of American democracy, is at stake, and the inexorable laws of history will permit no further compromise in its application.

Editorial from Jewish Life, the predecessor to Jewish Action, June 1958.

Beyond “We Shall Overcome”

Behind Selma and the Freedom March, behind all the epochal struggles of our time, lies the search for self-definition. Within a brief span of history, man and society and the whole human environment have undergone metamorphosis. Amidst revolutionary change, with the universe emerging in new form before man’s startled gaze, with accustomed landmarks swept away, mankind stands at a loss, bereft of a sense of clear identity. Powers such as man never before has known are now at his disposal. But how—that is, in what terms of binding moral reference—these powers are to be used, must remain a disaster-fraught riddle unless and until man’s essence and purpose be freshly perceived. Pending such fresh perception, rights, right itself, become a provisional proposition, with status in the scheme of things governed factually by relation to command of modern power positions. The striving for better status, whether national, group, or individual, finds ideological expression which, for all its fluency, fails to give form or voice to the innermost quest. It is significant that the posuk “And G-d created man in His own image” is so often drawn upon in support of the civil rights movement. The Torah word rather than the contemporary idiom bespeaks what lies deepest in human motivation today.

It is man’s vision of himself and of ultimate verities that is at stake in the turbulence of our times. This is not to be gained through “modern resources”; rather, it can well be lost by their blandishments. Only in opening our eyes to a timeless resource, the vision of man as bearer of the Divine Image, can man recognize himself and perceive the meaning and purpose of his life, and only so can he know and do what is right and what is just.

Once, long ago, our own people was brought forth from bondage to be vouchsafed this vision and to cleave to it and bear it aloft to the world. We relive this cosmic happening now and know, with renewed understanding, what great task is entrusted to us.

Editorial from Jewish Life, the predecessor to Jewish Action, spring 1965