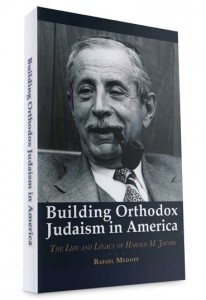

Building Orthodox Judaism in America: The Life and Legacy of Harold M. Jacobs

By Rafael Medoff

By Rafael Medoff

304 pages

Reviewed by David Luchins

The story is told of a visitor to the Netherlands who was given a lengthy tour of that nation’s extensive system of dikes and asked, “How often does it flood around here?” When he was told “it hasn’t for the last fifty years,” he asked, “Then why do you need to spend so much time and money on these dikes if it doesn’t flood here anymore?”

Some readers may experience similar questions when picking up Rafael Medoff’s fascinating book Building Orthodox Judaism in America: The Life and Legacy of Harold M. Jacobs. “Why,” one might ask, “did Harold M. Jacobs spend so much time and exert so much effort for causes that seem so unnecessary to us?” The answer, of course, is that Harold Jacobs and a handful of intrepid, inspired individuals won these battles so decisively that our generation has the luxury of taking their accomplishments for granted.

To read Harold Jacobs’ life story is to read the astonishing story of twentieth-century American Orthodoxy, from a pitied anachronism to the most vibrant and fastest-growing segment of contemporary American Jewish life.

Harold and his friends Moses I. Feuerstein, Harold H. Boxer, Dr. Bernard Lander, and, lehavdil bein chaim lechaim, Rabbi Joseph Karasick—still going strong in the leadership of the Orthodox Union well into his tenth decade—built the protective dikes and poured the institutional foundations that have helped create the unprecedented and unpredicted revival of Torah Judaism across North America.

Harold was a first. A member of the first class of Yeshiva Torah Vodaath (Brooklyn’s first yeshivah day school), a first-year camper at America’s first kosher overnight summer camp, the first outspoken, unmistakably Orthodox voice in the corridors of American political power in general and public higher education in particular (where he helped save the CUNY system as chairman of the CUNY Board of Trustees).

Harold came of age in an era that has been described as “fluid Orthodoxy,” in which the vast majority of the members of Orthodox synagogues were not personally Sabbath observant. His parents were the exception. His father, Max, was a proud (and quite successful) shomer Shabbat businessman and his mother, Kate (Kaila), was a pious woman and the primary force behind the construction of the first public mikvah in Brooklyn.

Who remembers the blue laws that forced Sabbath-observant places of business to be closed on Sunday as well? Ironically, the kosher butchers’ union was a major supporter of blue laws, because of an exemption clause that allowed butchers, and often only them, to do business on Sundays in New York State. After years of futile effort, it was Harold who forced future Assembly Speaker Stanley Steingut to agree to the repeal of this onerous legislation by challenging him in a Democratic primary and garnering so much support that a stunned Steingut agreed to switch his position in exchange for Harold dropping out of the race.

The reader of an “authorized biography” usually expects a lightly sourced, airbrushed version of history, in which the subject of the biography plays a larger-than-life role. If anything, this meticulously sourced and vigorously footnoted work understates Harold Jacobs’ significant part in maintaining Black-Jewish relations during a very difficult time; his critical role in Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s initial 1976 Senate election (and how the senator cherished Harold’s advice and friendship), his vital assistance in securing Touro College’s New York State charter and, perhaps of most interest to readers of this magazine, his historic contribution as the only person to hold the top leadership positions in both the National Council of Young Israel and the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America (now known as the Orthodox Union).

Harold’s eight years as board chair and six years as president of the OU were among the most important in the organization’s history. Rabbi Karasick and Harold reframed and redirected the OU’s mission and mandate. NCSY was transformed from a tentative local-based organization into a continent-wide powerhouse. The OU established a presence in Israel via the World Conference of Synagogues and the OU Israel Center (now the Seymour J. Abrams Orthodox Union Jerusalem World Center). The first steps were taken to expand the role of women in the OU leadership with Harold appointing the first women directors in 1976 and making the first effort, more recently realized, to select women as officers. And the aging leadership of the OU was invigorated by a cadre of young leaders, many of whom were handpicked by Harold and remain active in the OU to this day. Several of these efforts were matters of considerable controversy at the time, as were Harold’s attempts to end the OU’s controversial participation in the Synagogue Council of America. There was considerable tension and dramatic confrontation.

Rafael Medoff does not pull any punches in reporting on these stormy debates and principled disagreements (albeit with a mistake or two in the dates and locations of key votes). This painstakingly researched and splendidly written book will help explain exactly who built those dikes and why we don’t worry that much any more about those floods.

David Luchins, PhD, chair of the Political Science Department of Touro College, served on the OU Board during Harold Jacobs’ presidency.

Building Orthodox Judaism in America can be purchased at Amazon.com