Debating Orthodox Judaism: A Tale of Two Rabbinical Seminaries

Two prominent institutions in Chicago’s West Side back in 1927, the Jewish People’s Institute (left) and the Hebrew Theological College (right), invigorated Orthodox life. Courtesy of Dr. Irving Cutler

Ninety years ago, in September 1927, two yeshivot came together to debate the future of Orthodoxy in America.

By Zev Eleff

In September 1927, more than a thousand women and men attended a debate at the newly built Jewish People’s Institute on Chicago’s West Side. The unusual contest featured rabbinical students from the local Hebrew Theological College and the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in New York. The young men took the competition quite seriously. Months earlier, the Chicago yeshivah held a tryout and then organized a regimen of practice sessions for the four chosen HTC debaters.1 Similar preparations were tended to in New York.2 The question for debate was whether the “parochial school system is the sole solution to the problem of the permanency of traditional Judaism in America.” Though still few in number, day schools—as an idea, anyway—had gained considerable sympathy within Orthodox sectors. Once considered the prime method of Americanization, public schooling and afternoon Talmud Torah education had lost some luster in these traditionalist locales. Drawing upon this, and sporting a refined rhetorical form, the New Yorkers triumphed, much to the chagrin of the local supporters.3 Years later, one of the Chicago debaters, Rabbi Leonard Mishkin, took some solace in the fact that his team “came out on top as far as content and attitude.”4

The episode was the first of three public debates between the two fledgling American Orthodox rabbinical seminaries. Founded in 1922, HTC had ordained just about two dozen rabbis, but aspired to install its modern-thinking and tradition-clinging men throughout the Midwest. In New York, RIETS had overcome a number of false starts. By the late-1920s, the school had secured the needed funds and commenced construction of a new campus in Washington Heights. In the recent past, the Manhattan students had struggled to obtain pulpits against the fierce competition of the nearby Jewish Theological Seminary. The new, fashionable school site offered more than a modicum of hope that the situation would be different in the near future.

The episode was the first of three public debates between the two fledgling American Orthodox rabbinical seminaries. Founded in 1922, HTC had ordained just about two dozen rabbis, but aspired to install its modern-thinking and tradition-clinging men throughout the Midwest. In New York, RIETS had overcome a number of false starts. By the late-1920s, the school had secured the needed funds and commenced construction of a new campus in Washington Heights. In the recent past, the Manhattan students had struggled to obtain pulpits against the fierce competition of the nearby Jewish Theological Seminary. The new, fashionable school site offered more than a modicum of hope that the situation would be different in the near future.

The HTC-RIETS debates, then, represented a revitalized spirit and confidence in the prospects of Orthodox Judaism. Moreover, it was a religious fervor that sprang from the minds of young people, the usual demographic responsible for awakenings in American Judaism. The embrace of open and organized discussion on marquee matters and the public attention paid to these forums confirmed all this. In truth, the debates and the interwar religious awakening were ephemeral. Orthodox Judaism would wait another two decades before undergoing a lasting revival in American Jewish life. Yet, the emergence of the debates signaled a kind of public discourse that later Orthodox leaders seized upon; and ones that might serve as models to engage present important discussions.

The success of the inaugural match inspired another bout. The rabbinical schools scheduled their second debate in December 1928, at the New York Seminary. This time, the Jewish press was better prepared to fête the competition. The major Chicago weekly declared that the cooperation between “Orthodox Jewry’s two great colleges of higher learning is considered of historic value by leaders of Jewry.” The journalists hoped that the meeting would “bring the two institutions close in spirit, as the aim of both is to strengthen Judaism in America.”5 Likewise, the Yiddish press in New York marveled at the sight of an “Inter-Yeshivah Debate.” Actually, the program was part of a much larger celebration of the Amsterdam Avenue campus that commenced with the launch of Yeshiva College and culminated with the RIETS quadrennial ordination exercises. The theme of all of these initiatives was a harmonization of American life and Jewish tradition. In line with this strikingly American enterprise, one New York daily congratulated both yeshivot for producing “men who can speak in modern terms and who are cultured.”6 Another newspaper offered that the nature of the debate reflected the “firm entrenchment of Orthodox Judaism in the United States.”7

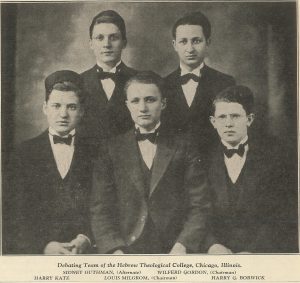

The HTC debate team, 1930. From left, standing: Sidney Guthman (alternate), Wilfred Gordon (chairman). Seated: Harry Katz, Louis Milgrom (chairman) and Harry G. Borwick. Courtesy of Rabbi Zev Eleff

The debaters also recognized the significance of the moment. Accompanied by President Saul Silber, the Chicago squad described its eastbound trip to the “great Yeshiva” in Manhattan as something of a “good-will mission.” The HTC team captain prayed that the “two Colleges will realize that they do not stand isolated in their noble task for the furthering of the ideals of traditional Judaism in this country.” Rather, he concluded, “they are linked by a spirit of affection and sincere brotherhood.”8 The RIETS students agreed, adding that from a cultural point of view, “this exchange of ideas on a vital Jewish topic will not only benefit the two institutions involved, but that it will also tend to create a keener interest in Jewish thought and Jewish problems among thousands of our fellow Jews.”9 Accordingly, and similar to the stakes of the earlier debate, the second installment drew upon one of the more vexing challenges of American Jewry and counted on a younger generation to inspire solutions.

The event did not disappoint. To endow this second debate with all-due import, the New Yorkers arranged for three judges: members of Mizrachi (Religious Zionists of America), the Agudath Israel and the Orthodox Union, at that time probably the most important advocate of America’s Orthodox Jews. Two thousand people, with their curiosity piqued, filled the grand auditorium. The debaters, dressed in tuxedos, wing collars, bat ties and “with yarmulkes on their heads made a very fine appearance.” The question for consideration that evening was the “problem whether the cultural development of Judaism depends on the restoration of Palestine.” The seminaries chose this subject on account of the Orthodox community’s unique synthesis of Jewish and American cultures. Unlike most Reform Jews, who avoided support of Zionism out of fear that it might “mar our patriotism,” the Orthodox argued that their sophisticated blend of “tradition” and “modern” sensibilities offered them courage to stake out bold and creative positions.10 The aspiring rabbinical scholars took the issue quite seriously. Here are the recollections of one of the RIETS competitors:

The RIETS debate team, 1930. From left, standing: Emanuel Rackman, Moses Mescheloff (alternate). Seated: David Rubin and Max J. Wohlgelerenter (captain). Courtesy of Rabbi Zev Eleff

We took the debate very seriously, and researched the background thoroughly. I was to deal with the historical background of the Zionist movement and the concept of Statehood in Jewish history. So I spent a good deal of time in various libraries studying ancient as well as modern sources, as did my colleagues. We had adopted the negative side of the question, and, therefore, had the more difficult case to argue; it was also less popular.11

This turned out to be the difference in the match. Observers noted the finely modulated voices of the debaters, and found that both teams were “oratorically equal.” The final tally came down to argumentation. Two of the three judges sided with the RIETS men, probably because the Chicagoans “did not hold strictly enough to the main points of the debate.” The HTC students reportedly relied too much on “propaganda” and their “enthusiastic spirits” rather than facts. The Chicago crew settled for serving as the people’s champion. Just as the RIETS students had anticipated, the final decision was “decidedly unpopular.” The audience had cast the RIETS group as the “anti-Zionist theologians.” They would have much preferred the judges to resolve in HTC’s favor.12

In all likelihood, both rabbinical schools and their constituencies anticipated this contest to remain an annual tradition. It sparked pleasant conversation and accrued valuable cultural currency. That young people had accomplished all this provided boundless hope for the future of Orthodox Judaism in the United States. Nonetheless, the third debate took place amid a good degree of caution. The onset of the Great Depression severely stunted the growth of the Chicago and New York yeshivot. The schools postponed the next disputation to July 1930. Still, rather broke, and unable to cover other valuable operational expenses, the leaders of both schools were unwilling to cancel the arrangement, despite the considerable costs.

The students, however, were hardly of one mind on the matter. Some were very far from sanguine. They questioned whether mere “good-will” was sufficient cause to maintain the debate tradition. To a group of Chicagoans, the whole enterprise appeared contrived, never fully achieving a “oneness of purpose” among the two Orthodox centers.13 They yearned for cooperative ventures in Torah study and more meaningful ventures between Chicago and New York. Still, other young men parted company with the pessimists. Excited to joust over the role of the Orthodox rabbinate in the modern world, the topic was a welcome one to the seminarians who desperately wished to dispel the notion that they were “oblivious to the hurly-burly of modern life.”14 On the other side, the New Yorkers, represented by Moses Mescheloff—later, in 1954, he assumed a prominent pulpit position in Chicago—described the debate as an “oasis of learning.”15 The students and their communities anticipated another sophisticated and relevant discussion led by budding future leaders. This offered ample cause for a third round. Once again, the two squads met at Chicago’s Jewish People’s Institute, the site of the inaugural affair. The RIETS team was tasked with arguing that the “drift of the American rabbi into the status of social director is detrimental to Judaism.”16 The Chicago men prepared the rebuttal. Just like the previous topics, the subject of this 1930 competition struck at the core of Orthodox Judaism’s relationship with current American cultural trends and politics.

This offered ample cause for a third round. Once again, the two squads met at Chicago’s Jewish People’s Institute, the site of the inaugural affair. The RIETS team was tasked with arguing that the “drift of the American rabbi into the status of social director is detrimental to Judaism.”16 The Chicago men prepared the rebuttal. Just like the previous topics, the subject of this 1930 competition struck at the core of Orthodox Judaism’s relationship with current American cultural trends and politics.

Yet, something missed the mark this time. The general director of the Jewish People’s Institute reported that the “theater on this occasion was crowded to its capacity.”17 Apparently, though, this was a smaller theater compared to the one used for the earlier competition held at this site. In all, about 500 people attended the debate; a considerable figure but much less than the number that attended the previous two matches. Perhaps, much too overwhelmed by the nationwide economic situation and mounting political conditions overseas, the local press neglected to cover the event and report the winner. Likewise, pained by a paucity of resources, and hindered by the increasing rise of the Conservative Movement, Orthodox Judaism started to regress and enter a troubling period of religious depression. It was therefore the final debate between the Chicago and New York yeshivot.

The so-called “lean years” persisted for several decades. In the 1950s, young Orthodox Jews searched for a way to jumpstart a revival. In fact, HTC students heard rumors that they might “see the resumption of the debates between Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Yeshiva and the Hebrew Theological College.”18 In the end, a fourth debate never took place; the time was not yet ripe for a young people’s awakening. Instead, the sentiment resonated for another decade or so. In the 1960s, young and inspired day school graduates assumed an integral role in the long-lasting revival in Orthodox Jewish life. Through educational initiatives such as NCSY and the intercollegiate Yavneh organization, as well as Yeshiva University and later incarnations of Jewish higher education, young people reemerged as the prominent voices for sophisticated conversation on meaningful issues. They routinely debated Jewish education, scholarship, the modern synagogue and Vietnam. Of course, it was a formula of discourse put into action long before—and one that can stimulate a renaissance once again.

Notes

1. Theological College Selects Debaters,” The Sentinel, August 5, 1927, 32.

2. “School to Hold Debate,” The Sentinel, August 19, 1927, 32.

3. “Yeshiva Students Win Debate on Advisability of Parochial Schools,” Daily Jewish Courier, September 22, 1927, 2.

4. Leonard C. Mishkin Interview, March 4, 1978, Chicago Jewish Historical Society Oral History Project, Chicago, Illinois.

5. “Hebrew Theological College to Meet New York Seminary in Debate,” The Sentinel, December 14, 1928, 29.

6. I. L. Bril, “The Inter-Yeshiva Debate,” Der Tog, January 6, 1929, 5.

7. “The Debate Between the Yeshivahs,” Morgen Zshurnal, January 2, 1929, 3.

8. Philip Graubart, “Ambassadors of Good-Will,” Hedenu 4 (December 30, 1928): 2.

9. Hyman J. Routtenberg, “Welcome!” Hedenu 4 (December 30, 1928): 3.

10. Samuel Rosen, “The Subject—Why?” Hedenu 4 (December 30, 1928): 2.

11. Israel Tabak, Three Worlds: A Jewish Odyssey (Jerusalem, 1988), 143. Many thanks to Chaim Reich for pointing out this valuable source to me.

12. See Bril, “The Inter-Yeshivah Debate,” and “The Debate Between the Yeshivahs.”

13. “Debates,” Hamayon 5 (summer 1930): 6.

14. David Rubin, “The Significance of the Debate,” Hamayon 5 (summer 1930): 9.

15. Moses Mescheloff, “Greetings,” Hamayon 5 (summer 1930): 9.

16. “Shebouth Proves Inspiration to Inter Yeshiva Debaters,” The Sentinel, June 6, 1930, 40.

17. Philip L. Seman, “Jewish Activities,” in Vision and Experiment in Community Service (Chicago, 1931), 77. My thanks to Simcha Freedman for helping me retrieve this source.

18. Norman Fredman, “For Batlonim Only,” The Scribe 4 (Hanukkah 5710): 7.

Rabbi Dr. Zev Eleff is chief academic officer of the Hebrew Theological College in Skokie, Illinois, and associate professor of Jewish history at Touro College and University System.