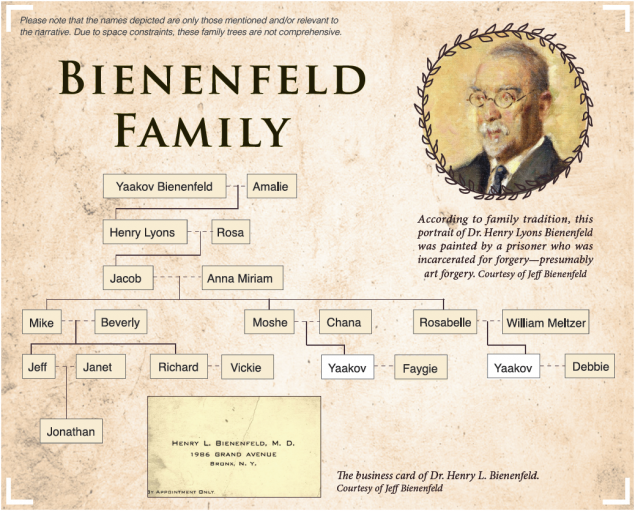

The Bienenfeld Family, New York

Yaakov Bienenfeld, a descendant of the famed Rema, emigrated from Austria to New York in the 1840s. Part of a wave of German-Jewish immigration to the US, he came to escape poverty and oppression and seek a brighter future. His son, Dr. Henry Lyons Bienenfeld, was a medical doctor and one of the first American-born Orthodox rabbis.

By Rabbi Yaakov Bienenfeld, great-great grandson of Yaakov Bienenfeld; rav of the Young Israel of Harrison, Westchester, New York

I’m named after Jacob, my grandfather, who was named after Yaakov Bienenfeld, the patriarch of this family and my great-great-grandfather who came to the US in the 1840s. When he first came to New York, he settled in Harlem, where a Jewish community existed at the time. Many of the big churches in Harlem today used to be shuls. Additionally, most of the big shuls in Manhattan today were built in the 1800s, such as the West Side Institutional Synagogue, Congregation Ohab Zedek, Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun and Congregation Shearith Israel (the Spanish & Portuguese Synagogue).

In 1856, Yaakov Bienenfeld’s son, Henry Lyons, my great-grandfather, was born. Some time later, Yaakov was drafted to fight in the Civil War. When President Lincoln came to New York City, Yaakov took young Henry to the parade and they both got to meet the president and shake his hand.

Dr. Henry Lyons Bienenfeld was a huge talmid chacham. There were no yeshivot at the time; his father taught him how to learn Gemara. He was also a brilliant medical doctor who graduated from NYU School of Medicine in 1884. I have his writings on parts of the Talmud; he’s also quoted in sefarim. I have copies of the letters he wrote on Jewish philosophy that are currently found in the New York Public Library archives.

In the 1920s and ‘30s, Dr. Bienenfeld served as the chief physician of the New York City prison system. In addition, he had a medical practice on 110th Street in Harlem. My aunt, Rosabelle Bienenfeld Meltzer, remembered him riding around in his horse-drawn carriage making house calls.

Dr. Bienenfeld started the first kiruv organization in America, called The Advancement of Jewish Learning, to teach Americans [from immigrant families] who didn’t know much about Judaism. He was one of the few English-speaking talmidei chachamim at the time in the country. Totally Americanized, he found it difficult to express himself in Yiddish. When the family would prepare to bentch after eating a seudah, he would say, “Gentlemen, let us now say grace.”

When his son, Jacob Bienenfeld, my grandfather, was born in 1888, the family was second-generation American; Jacob was one of the first American-ordained Orthodox rabbis raised in an American home. The family valued education, both secular and Jewish. Jacob attended Columbia University and worked in the public school system as a math instructor; he also held degrees in philosophy and law. He finished Shas many times and served as a rav in downtown Manhattan.

When Jacob wanted to start dating in 1910, he asked his father, Dr. Bienenfeld, for permission to do so. His father responded, “Did you finish Shas three times and Shulchan Aruch once? You can’t get married unless you’ve done that.” They took learning seriously. That’s what enabled them to stay frum.

In the early 1900s, when Jewish communities took off on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and in Brooklyn, Dr. Bienenfeld and his son, Jacob, were some of the first in America to deliver daf yomi shiurim in English, as few rabbis were able to do so. Someone I once met told me he remembers the summers when Jewish immigrants would vacation in Sharon Springs or Lake Mohegan, and Dr. Bienenfeld would deliver the daf yomi shiur. When he had to return to work in the city, his son Jacob would teach daf yomi. When the community needed someone to represent them for political or educational reasons, my great-grandfather and grandfather were the go-to people. At one point, a few observant Jews approached my grandfather, and asked if Coca-Cola could be certified kosher. He was the first rabbi to give Coca-Cola a hechsher in 1930.

Dr. Bienenfeld lived into the 1940s. Many of his descendants are rabbanim or in chinuch. Most notable is his great-great-grandson, Rabbi Jonathan Bienenfeld, rav of the Young Israel of Cherry Hill in New Jersey.

By the time my father, Moshe, was born, yeshivot existed in America. He and his brothers attended Yeshiva D’Harlem on 114th Street and then Yeshiva Torah Vodaath in Williamsburg, Brooklyn in the 1920s and ‘30s.

A young man working on a doctorate in sociology devoted his thesis to the subject of German Jewish immigration. He told my cousin that our family’s story is very unusual. He said, “There aren’t many German Jewish families [In the US so long] I’ve studied who remained frum. It’s remarkable that yours is.”

By Yaakov Meltzer, cousin to Rabbi Yaakov Bienenfeld

My mother, Rosabelle Bienenfeld, was born in 1920. (She passed away recently at the age of ninety-five.) She didn’t have a formal Jewish education. Education came from the home. She was taught how to kasher meat, hilchos Shabbos, et cetera. Her father, Jacob, was a rav, so she was able to ask him any question she had.

My sense is that it wasn’t hard for them [to be frum]. From how my mother portrayed it, there was never a thought that being frum was a challenge; being frum was never a she’eilah.

They were brought up with a reverence for Torah. My mother recalled how her father, Jacob, and grandfather, Dr. Bienenfeld, were always learning.

There’s a famous Kotzker vort. Someone came to the Kotzker Rebbe and asked, “How can I encourage my son to learn Torah?” The Rebbe said, “You have to learn. Just telling your son to learn Torah will result in him growing up and telling his own children to learn Torah. Only if you learn Torah yourself will your son grow up to learn Torah.” In the Bienenfeld family, the children saw that their fathers always learned in their free time.