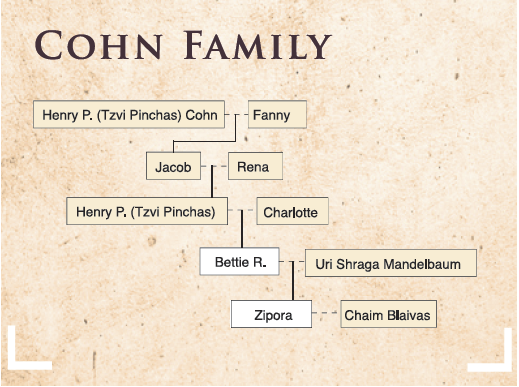

The Cohn Family, Baltimore, Maryland

Henry P. (Tzvi Pinchas) Cohn left Germany for America around 1847. In the States, Henry married his cousin Fanny, who had been living in Virginia. Today, the Cohns are seventh-generation Americans and shomrei Torah and mitzvos.

By Bettie R. Mandelbaum (nee Cohn), great-granddaughter of Henry P. (Tzvi Pinchas) Cohn

My great-grandfather, Henry P. (Tzvi Pinchas) Cohn, was a Kohen. He left Germany because they had strict laws against Jews there, one of which imposed limitations on how many Jews in a family could get married. (This is why one of Yekke minhagim is that talleisim are worn by both single and married men; this way, German officials weren’t able to tell who was married and who wasn’t.) Before he left for America, Henry received a license to perform shechitah, since he was unsure if he would be able to obtain kosher meat in America.

When Henry first came to America and settled in Richmond, Virginia, he was a peddler. He married his cousin Fanny and in the middle of the Civil War, the couple moved to Baltimore. I assume they moved because it was easier to maintain an Orthodox life in Baltimore, which had attracted a relatively large number of Orthodox Jews. It was important to have other frum people to socialize with. Without a support system, one was likely to assimilate.

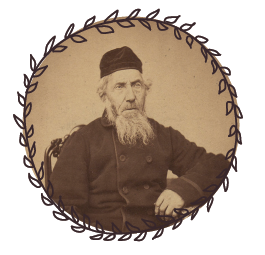

Simcha Katz, circa 1874, father of the original Henry P. Cohn. In 1874, Henry went back to visit his father, who had remained in Germany. Henry kept a diary and wrote many letters back to his family over the course of the trip. Courtesy of Howard M. Cohn

In 1863, during the Civil War, Henry paid a mercenary to fight in the war for him; the going price was a thousand dollars. In 1874, Henry traveled by ship back to Germany to visit his father, Simcha Katz (my great-grandfather changed the name to Cohn in America). The trip took about three weeks. On the ship he kept a diary in German and wrote letters to his family. I have the diary and the letters, which have been translated into English.

When he returned to Baltimore, he opened a small department store called The Favorite, which was closed on Shabbos. Anybody in Baltimore who wanted to keep Shabbos could get a job working there. The store would open on Motzaei Shabbos with lines of loyal customers waiting to enter.

While living in Richmond and in Baltimore, my great-grandfather, Henry P., wrote she’eilos to Rav Shmuel Salant in Yerushalayim and received written teshuvos, several of which we still have. The Cohns always stressed the importance of being close to a rav.

How did my great-grandparents stay frum in America, and not succumb to assimilation despite all of the challenges? They had backbones made of iron rods. The Torah was their guide and that was it; there was no

other way. That’s how I was brought up. My mother told me that we were not to wear red because of a cherem of the Chasam Sofer. And that was finalóthe Cohns don’t wear red.

When I was a child, because most store-bought foods had no hashgachah, at home we wouldn’t eat anything [commercially processed]. We did everything ourselves, including grinding our own coffee beans. I didn’t know what candy was growing up because we couldn’t buy anything from the store. My family was stringent about the male adults only consuming cholov Yisrael. My mother would drive my grandfather Jacob to a farm every week and they would pasteurize the milk themselves and make cottage cheese. My grandparents, who lived around the corner from us when we were growing up, were known in Baltimore as the “Fruma Cohns.” As a little girl I used to watch my grandmother Rena kasher the chickens. Their [spiritual] strength and commitment to [Judaism] were passed down through the generations.

By Zipora Blaivas, daughter of Bettie Mandelbaum

A young Jacob Cohn, son of the original Henry P. Cohn. One of nine children, he was one of the few to marry, as there was a dearth of frum Jews in the US at the time. Courtesy of Howard M. Cohn

My great-grandfather, Jacob Cohn, was one of nine children; Only three of those children ended up getting married, as there were a limited number of frum Jews to marry in America. They were proud German Jews whose dedication to Yiddishket precluded them from considering marrying out of the religion. When Jacob was in his upper twenties, he contracted a deadly illness. He made a neder that if Hashem healed him, he would get married and try to have a family. Baruch Hashem, Jacob recovered and married my great-grandmother, Rena (Rivka) Glass, who was also from a Jewish-German family.

In 1930, when my grandfather, Henry P. (Tzvi Pinchas) (named after his grandfather, the original family patriarch) got his first job, he told his boss that because of Shabbos he would leave early on Fridays. After a couple of weeks, his boss asked him, “How long are you going to do this leaving early on Friday thing?” His boss thought it was a passing phase. My grandfather answered, “As long as I’m alive.” Compromising on religion wasn’t an option. Rumor has it that he didn’t wear a yarmulke at work and because of this he didn’t eat while at work. He would eat in the morning before he left and when he returned home. When my grandfather came home with his first paycheck, he put aside some of the money in a little box designated for ma’aser and told my grandmother, “This money does not belong to us.”