The Story of the Synagogue Chumash

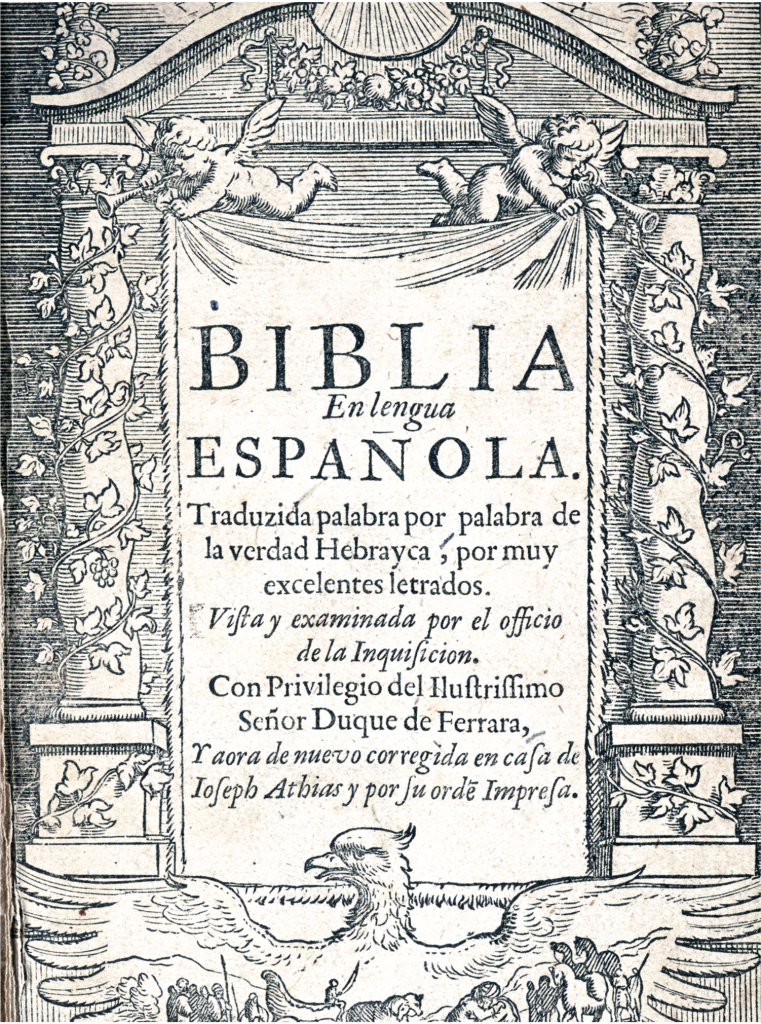

The Ferrara Bible, the first printed Spanish translation of the Chumash by ex-converso Solomon Usque, was originally published in 1553. The title page here is from the 1661 edition. Courtesy of the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania

When you walk into shul on Shabbat morning, which Chumash do you choose? Do you take one with Hebrew only, or one with English translation and commentary? Do you use the ArtScroll? Something else? How much thought do you put into your choice?

Obviously, every shul Chumash contains the same Torah, but each edition has its own flavor. It’s worthwhile to consider how they differ, for the story of the Chumash is the story of how the timeless Torah continues to be presented in new ways.

First, what is a Chumash?

In the Mishnah (Yoma 7:1 and others), the word chumash refers to a chomesh—one-fifth of the Torah (i.e., one book). Over time, however, the word came to mean what it does today, an abbreviation for Chamishah Chumshei Torah—a single book or codex containing all five-fifths of the Torah.

The codex, or bound book, was invented around the year 300 ce, but we do not have any Chumashim that old; the earliest ones we have today are from around 1,000 years ago. Chumashim were not widely available in the Middle Ages, as only wealthy individuals could afford a scribe to write the manuscript. Although they were not produced exclusively for synagogue use, many medieval Chumashim contain haftarot or even Shabbat davening, suggesting that they were intended to be used in shul. The invention of the printing press (in the fifteenth century) made Chumashim more affordable and widespread.

A Survey of Translations

In today’s user-friendly shul Chumashim, translation is a central component. Surveying these translations will help us understand the differences between the editions available today.

The Mishnah in Megillah (4:4) recounts the ancient practice of oral translation: after the Torah reader completed one verse, a designated individual would recite the Aramaic targum, or translation, aloud. The Gemara (Megillah 3a) traces this practice all the way back to Ezra’s public reading of the Torah (Nechemiah 8:8). Some targumim, most famously Targum Onkelos, are largely literal renderings of the Torah. Others, such as the one commonly known as Targum Yonatan ben Uziel, are far more midrashic, expanding upon the Torah’s narrative with interpretation and even lengthy additions.

Beyond Targum, the Torah has been translated into the vernacular of nearly every land that Jews have called home. The Greek Septuagint was probably completed a few hundred years before the Common Era. There is also Rav Saadiah Gaon’s tenth-century Arabic Tafsir. The ex-converso Solomon Usque’s 1553 Ferrara Bible was the first printed Spanish translation of the Torah. And the noted scholar and commentator Rabbi Samuel David Luzzatto, or Shadal, published a translation of the Torah into Italian in 1858.

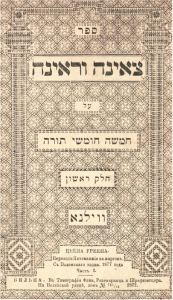

Tz’enah Ur’enah, a free-flowing midrash on the Torah, was reprinted hundreds of times after being published ca. 1600. This 1877 Vilna edition was rescued from the Nazi Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (EER) unit and returned to YIVO by the US Army after World War II. Courtesy of the Library of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York

Translation did not take hold with the same fervor in Yiddish-speaking parts of Europe. Despite an oral tradition for translating individual Hebrew words in the Torah into Yiddish dating back to the Middle Ages, few full Yiddish translations were attempted. One notable exception, the 1544 Taytsch Chumash, which was spearheaded by a Christian Hebraist publisher, was nearly unreadable due to an over-literal approach to translation that used Hebrew instead of Yiddish syntax. It sold few copies. Later Yiddish versions were called Chumash mit Chibbur, which was more of a running Yiddish commentary than a literal translation, with the interpretive portion frequently paraphrasing Rashi. More popular than any translation was Tz’enah Ur’enah, a free-flowing midrash on the Torah by Yaakov ben Yitzchak Ashkenazi. Tz’enah Ur’enah, first published around 1600, was reprinted hundreds of times in the following centuries. The popularity of Chumash mit Chibbur and Tz’enah Ur’enah demonstrates that for many traditional Jews, Chumash and Rashi were inseparable, and rabbinic exegesis and commentary were part and parcel of what the Torah really means.

It is in this very traditional milieu that Moses Mendelssohn made waves in 1783 with the first-ever German translation of the Torah. At first glance, Mendelssohn’s work, called Netivot haShalom, doesn’t look so different from the classic Mikraot Gedolot. Mendelssohn’s Be’ur commentary, for example, is in Hebrew and draws exclusively from traditional commentaries. But Mendelssohn also used Hebrew characters for the German translation, suggesting that he wanted traditional Jews to learn German and integrate into German society as he had. Indeed, Mendelssohn’s Chumash aroused the ire of some in the rabbinical establishment.

By the time Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch published a new German translation with his own extensive commentary in 1867, many more Jews spoke German, and Rabbi Hirsch saw a need to counter the growing Reform movement and to impart traditional values to an assimilating German Jewry. Unlike Mendelssohn’s commentary, Rabbi Hirsch’s is original, synthesizing his unique approach to Jewish thought, the meaning of mitzvot, and the etymology of Biblical language. Rabbi Hirsch’s commentary is particularly striking because it is one of only a handful of Torah commentaries written in the vernacular up until his time.

Contemporary Chumashim

English translation followed a different path. For quite some time, English-speaking Jews were content to use slightly modified versions of the seventeenth-century King James Bible—such as David Levi’s 1787 Bible or Michael Friedlander’s 1884 Jewish Family Bible—which remove overtly Christian renderings. Even the 1917 Jewish Publications Society (JPS) translation, which set the standard for scholarly English translations by Jews, relied on the King James instead of starting from scratch, and remains highly similar to it in substance and style; many verses are nearly identical.

Perhaps Jewish dependence on the King James speaks to how faithfully its translation hews toward literalism and how well it captures the rhythm of the Hebrew.

The story of the Chumash is the story of how the timeless Torah continues to be presented in new ways.

But not everyone was comfortable with the King James. Isaac Leeser, the nineteenth-century American communal leader, writer, and editor of the Occident, deplored Jewish reliance on “a deceased King of England, who was certainly no prophet, for the correct understanding of the Scriptures.” In 1845 he published his own Chumash, which includes his translation (ironically still quite similar to the King James) and a short commentary that largely paraphrases Rashi. Leeser’s Chumash was widely used in English-speaking synagogues until the early twentieth century.

You won’t find Leeser on the shul bookshelf anymore. But you will probably still find the Hertz Chumash. British Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz’s 1936 one-volume Pentateuch And Haftorahs was revolutionary. Although Rabbi Hertz used the JPS translation, he composed (with assistance) a wide-ranging English commentary highlighting traditional and modern scholarship that defends the Torah from Biblical criticism. The Hertz Pentateuch was the standard shul Chumash in American synagogues, Orthodox or not, until the 1980s and beyond. The Conservative movement used it nearly exclusively until 2003.

This is not to say that there were no alternatives to the Hertz Chumash. In 1947, the publisher Soncino released another English Chumash with the JPS translation, but instead of Rabbi Hertz’s commentary it includes summaries of comments by Rishonim such as Rashi, Ibn Ezra, Ramban and others. It was also quite popular, and you might still find it on the shelf. In 1983, Dr. Philip Birnbaum, famed for his “Birnbaum Siddur,” published a Chumash translation with a terse commentary, but I’ve never seen his Chumash in shul. Rabbi Hirsch’s commentary was excerpted and translated into English by Gertrude Hirschler in 1987, exposing synagogue goers to Rabbi Hirsch’s thought (although without the linguistic elements). The Hirsch Chumash is still widely used in shuls today, and has gone through several editions.

More significant from a translation perspective was Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s The Living Torah Chumash. First published in 1981 and then in a Hebrew-English edition in 1985, it was the first Chumash intended for shul use not shackled to the King James’ archaic language and flowery style. The Living Torah is light on commentary, but features a modern English translation and includes English subheadings to guide the reader topically. The Living Torah translation is refreshingly colloquial, but perhaps at the expense of being sufficiently literal. For example, Rabbi Kaplan translates “yom hasheviyi” in Parashat Bereishit as “Saturday.”

It was ArtScroll’s 1993 Stone Edition of the Chumash that set a new standard. In many contemporary middle-of-the-road and Modern Orthodox shuls, it now dominates the shelves. An attractive faux-leather volume with charts, pictures, a new translation and a commentary anthologized from a wide range of traditional commentaries, the Stone Chumash rapidly replaced the aging Hertz Chumash.

Return to Rashi

But the Stone Chumash is not an updated version of the Hertz. It does not attempt to engage Biblical critics, and in fact, its editors saw no need to draw on non-Jewish or non-religious sources at all. Instead, ArtScroll’s editors rely solely on traditional commentaries, and believing that Rashi most closely reflects Chazal’s understanding of the Torah, prioritize his commentary over others. Likewise, the far-less-popular 1999 Margolin Edition Torah from Feldheim Publishers (which does not include a commentary) emphasizes Onkelos and Rashi in its translation, explaining that a purely literal rendering of the words (if there is such a thing), is counter to the purpose of translation, which is to elucidate the text according to Chazal.

Beyond Targum, the Torah has been translated into the vernacular of nearly every land that Jews have called home.

The return to Rashi is most pronounced in two one-volume shul Chumashim published by different arms of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement. The 2006 Gutnick Edition, published by Kol Menachem, calls Rashi “basic to the understanding of the text of Chumash,” and states that each comment of Rashi, no matter how “elaborate it may be, is required in order to understand the literal meaning of Scripture.” Thus, its translation follows Rashi, and the commentary also focuses heavily on Rashi. This edition also includes many insights from the Lubavitcher Rebbe, who believed that Rashi was of supreme importance for understanding the Torah and spoke frequently about Rashi in his sichos.

The other Chabad Chumash, published by Kehot in 2015, goes even further and adds—or in its words, “interpolates”—ideas based on Rashi’s commentary and Midrash into the translation itself. Although the Chumash uses bold text for the literal translation and plain for the additions, it is hard to separate the layers from one another, and there is far more commentary than pure translation. This format harks back to the Yiddish Chumash mit Chibbur of centuries prior which, as noted, also wove Rashi into the translation.

A New Emphasis on Peshat

The editions that emphasize Rashi give short shrift to a more peshat-based approach that is experiencing a resurgence in Modern Orthodox communities. Enter the 2018 Steinsaltz Humash from Koren, a translation of Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz’s Hebrew Torah commentary. The Steinsaltz Humash does not rely primarily on Rashi; its translation and commentary is guided by Rashbam, Ibn Ezra and others who rigorously pursue peshat. As a nice touch, the Chumash also includes color diagrams, pictures and maps. However, the Chumash uses the “interpolated” format of the Kehot Chumash despite its very different agenda, interweaving Rabbi Steinsaltz’s commentary with bolded translation, and thus suffers from some of the same drawbacks. While Rabbi Steinsaltz’s use of bolded translation and plain-text explanation is similar to the format of his Talmud translation, it is more suited to the Talmud, since the terse and cryptic language of the Talmud requires more explanation.

In summary, recent editions have tried to make learning Chumash a more effortless, enjoyable and enriching experience, with features such as commentary and pictures.

Although it is axiomatic that the full and authentic meaning of the Written Torah can only be understood through the mesorah of the Oral Law preserved and transmitted by our Sages, our tradition recognizes a value in studying the syntax and structure of the text without the prism of commentary. The abundance of such commentary, especially when incorporated in the translation, makes this peshat endeavor impossible.

Where will the shul Chumash go from here?

The ArtScroll Chumashim remain dominant in synagogues, and have held up well over the years. It’s unclear whether any of the newer entries will make much headway; shelf space is limited.

But new Chumashim continue to be published nonetheless. I cannot conclude without mentioning Lord Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’ long-awaited edition, which perhaps will mark something of a return to the language and style of the Hertz Chumash.

The Chumashim available in shul are different from one another. They have changed and will continue to change. But the next time you walk into shul, you can make an informed choice.

Yosef Lindell is a lawyer, writer and lecturer living in Silver Spring, Maryland. He has written about shul Chumashim for the Forward and Lehrhaus. He has a master’s in Jewish history from Yeshiva University and his essays have appeared in the Atlantic and other popular and scholarly venues.