Boxes with Rainbows

In honor of the thirtieth anniversary of the Gulf War, we are reposting Toby Klein Greenwald’s article describing the fears, uncertainty, and miracles of those terrifying days. This was the first column the author wrote for Jewish Action.

There are so many images that are conjured up in my mind when I look back and reflect upon the Gulf War—the womb-like sealed room, the closeness of the family, the way casual acquaintances, and even total strangers, suddenly become talkative with each other, the understanding looks exchanged over store counters (“Do you have something comfortable?” “Oh, you mean, to wear in the sealed room. How about this…”), the afternoon weddings, the knowledge that one must get home before dark, the panic at getting caught at a neighbor’s home after dark and, at the sound of the siren, running home fast, panting, to find the children ready, gas masks on, waiting for Ima so they can seal the door.

It was truly the children who surprised us all. They were steadfast, they were prepared, they were feisty, and if we had ever given them any lessons in faith and courage, we were now receiving lessons from them in return, multiplied tenfold.

One week into the war, which meant one week without school or kindergarten, and after numerous Scud alerts and adjusting rubber straps on little heads, I realized our five-year-old’s long John-boy haircut would have to go. Hillel sat quietly as I snipped and I remembered that the last time he had behaved himself during a haircut his reward had been pizza and ice cream. “What would you like as a prize?” I asked as I finished, and viewed the shorn blonde locks on the tiled floor. He turned soulful brown eyes to me. “To learn Torah with Rav Chanan.” Rav Chanan is Hillel’s kindergarten rebbe. I turned away and cried.

For the first time I fully understood the meaning of the midrash that related how, when the children of Israel came before God to receive the Torah; He asked what they would offer as a guarantee. After His turning down their offer of precious jewels and other wealth, they offered their children. God accepted, and the Torah was given.

During the first Scud attack, when my husband was in the army and I was alone with the children, I remember their help and support as an anchor of security that counterbalanced my intense feeling of surrealism as I taped the door, as I put the wet towel at the bottom, my hands shaking. I kept thinking, “I’m watching someone else, this isn’t happening to me.” I remember disobeying the civil defense instruction that said parents must put on their own masks before they help the children with theirs, before they put the infants into their protective tents. And I wondered how many other mothers broke that rule.

I remember the Friday night I had dared to take the baby to shul with me (only a few minutes from home). I suddenly found myself running home with him in my arms, the siren sounding so close, shrieking in my ears. And thirty minutes later, around the Shabbat table, by the light of the candles, we were silently begging the angels of peace to stay.

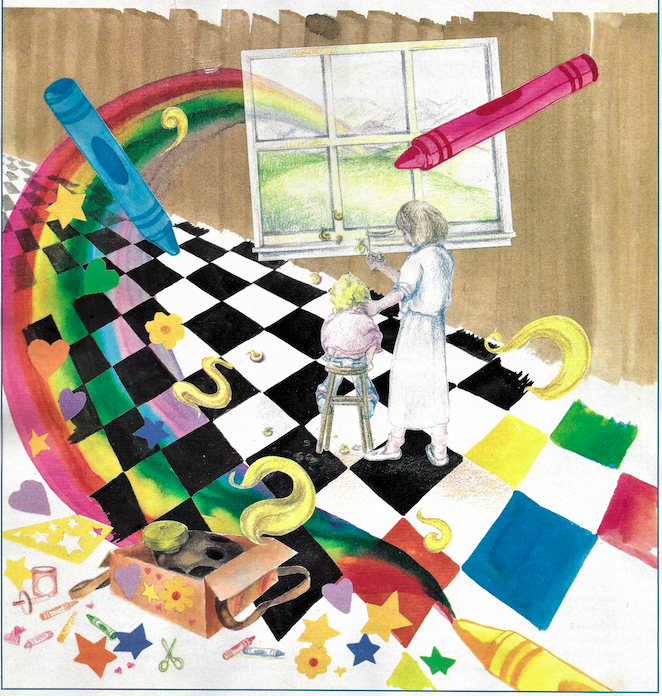

I can still see, in my mind’s eye, the children on the pathways, climbing the hills and crossing the valleys on their way to school, with bookpacks and the ubiquitous gas mask boxes. Some were decorated with cloth collages, others with colored paper. My own children spent a whole afternoon cutting and pasting and drawing, decorating these shields against death with hearts and balloons, flowers, their names, stars and rainbows.

This is their answer to Saddam Hussein, I thought. He sends Scuds, they want to learn Torah. He threatens us with annihilation, they draw rainbows on boxes.

People have spoken of the miraculous, of how it was no coincidence that the war began the week that we read Parashat Bo, in which the evil Par’oh is overcome and how it ended on Purim, with the hanging of Haman. This time, too, there were miracles.

But I cannot forget that there were other times, when the miracles did not occur. This was the first war during which Israelis did not sit by the radio in trepidation, terrified with each hourly news broadcast of hearing familiar names who had become battlefield casualties. This time, we were not ‘involved.’ To politicians sitting in Washington, ‘involved’ meant nameless faces in cockpits of fighter planes bombing missile launchers. To we who have lived here for many years, ‘involved’ means, who will not come home?

And there were other eras, other Purims, when the creative barbarism of twentieth-century Germany (or eleventh-twelfth century Ashkenaz, or fifteenth-century Spain, or seventeenth-century Poland) brought in its wake terrible suffering and sorrow. There were children in other eras whose war experiences did not culminate in drawing close to their parents in warm, cheerful rooms, surrounded by books, toys and love. With all the pain we feel for the injuries and homelessness of those who were hit in the Tel-Aviv area, we know it could have been much worse, and they have been the first to say, it was a miracle.

Now, while we can truly rejoice that the worst did not come to pass, that we were never forced to inject our children and ourselves with those obscene atropine shots, that the decontamination powder remained untouched, and that the sterile gauze can now be used, not to brush that powder off, but to cover skinned knees and summer bruises—perhaps now is the time to ask ourselves why, for us, did it end differently?

The author’s daughter Ephrat removing the tape and nylon from the sealed room’s window on Purim morning, the day the war was over.

On Purim morning, as we joyfully peeled off the tape and ripped open the layers of nylon covering our sealed window, as we gasped for air davka from that window, that happens to face Jerusalem, overlooking those particular hills, it seemed like the ripping open of a womb, with a child emerging, gasping for breath, crying with joy.

That night, the last vestiges of clear tape still sparkled like frost in the dark on the naked panes, merging with the stars.

When the war began, we took with us into the sealed room gas masks and bottled water, a transistor radio, food supplies, magazines and coloring books. I chose symbolically, and took in a siddur of my mother’s, her own, that had been worn with use even when she gave it to me, and an old siddur of my father’s, that was 1941 US Army issue. As strongly as I sensed the bond with my children, with the future, I wanted to feel the bond with the past. When my parents called to ask if we were safe, I was able to say, I prayed from your siddurim.

We took into our sealed rooms fears, and uncertainty, and prayers. We must now ask ourselves what we brought out.

Toby Klein Greenwald is an award-winning journalist and theater director.