On and Off the Beaten Track in. . . Hamat Tiberias

The seventeen springs of Hamat Tiberias have been known for their curative properties since antiquity.

Photos: Jack Hazut

www.israelimage.net

Thermal wonders from the ancient world

According to our tradition, there are four holy cities in Eretz Yisrael.

Jerusalem, of course, is one of them. The others are Chevron (Hebron), Tzefat (Safed) and Teveria (Tiberias). Chevron is the site of Ma’arat Hamachpelah, the first piece of land purchased by a Jew in the Land of Israel, and for seven years, the city was the country’s first capital before King David captured Jerusalem from the Jebusites and consolidated his rule over all of Israel and Judea (see the beginning of II Samuel 5:4-5). Tzefat is viewed as the center of kabbalah, Jewish mystical thought, and it is where Rabbi Yosef Karo compiled the Shulchan Aruch in the sixteenth century.

Why is Tiberias included in the list of four holy cities? The first indication of the city’s holiness is in the Gemara, when it describes the exile of the Sanhedrin from the Temple and Jerusalem at the time of the Churban in 70 ce:

Correspondingly, the Sanhedrin wandered to ten places of banishment, as we know from tradition, namely, from the Chamber of Hewn Stone to Hanuth, and from Hanuth to Jerusalem, and from Jerusalem to Yavneh, and from Yavneh to Usha, and from Usha [back] to Yavneh, and from Yavneh [back] to Usha, and from Usha to Shefar’am, and from Shefar’am to Beit She’arim, and from Beit She’arim to Tzipori and from Tzipori to Tiberias (Rosh Hashanah 31a, b).

According to this text, the tenth and final stop of the Sanhedrin was the city of Tiberias. But this brief mention of Tiberias does not capture the full significance of the city. It was in Tiberias, along the shores of Lake Kinneret, where the scholars of Eretz Yisrael continued the process of the development of Torah Shebe’al Peh (Oral Law) in the second through fifth centuries that eventually resulted in the compilation of the Talmud known as the Talmud Yerushalmi (the Jerusalem Talmud). It is clearly not coincidental that the compilers of the Talmud in Tiberias called their work the Yerushalmi and not the “Teveriani”; they saw themselves as living in the shadows of the long-since destroyed Jerusalem and Beit Hamikdash.

The completion of the Jerusalem Talmud, which represents the scholarship of the rabbis of the Land of Israel, predates the Talmud Bavli (Babylonian Talmud) by about 200 years.

Like its more popular “twin,” the Yerushalmi is based on the Mishnah which had been finalized in Tzipori by Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi around 200 ce.

Archaeologists are today uncovering extensive sections of Tiberias from the period of the Sanhedrin and the Amoraim (scholars of the Talmud). One day in the not-too-distant future these excavations will undoubtedly be open to the public for exploration.

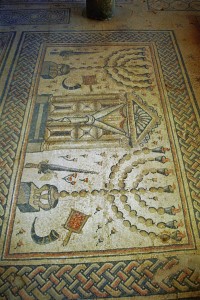

The central panel of the ancient mosaic floor of the synagogue in Hamat Tiberias National Park depicts the twelve signs of the zodiac with a Hebrew inscription for each. In the center is the Greek sun god, Helios. A woman’s face is portrayed in each of the four corners along with a Hebrew inscription indicating the season in the solar calendar (Tishrei, Tevet, Nisan and Tammuz corresponding to fall, winter, spring and summer).

Excavators are also hoping to uncover evidence that predates the period of the Talmud by over 1,000 years. As we learn in Masechet Megillah, Rakat (a walled city conquered by Joshua [19:35]) is identified as Tiberias. The verse also mentions a nearby town called Hamat (from the Hebrew word for heat), which archaeologists identify as a small settlement a short distance further south along Lake Kinneret, built directly on top of natural thermal hot springs.

One excavation site from the Talmudic period that is open to the general public is Hamat Tiberias National Park. The main focus of the park is a synagogue that was built between 286 and 337 ce, when the Sanhedrin was headquartered in Tiberias. The synagogue actually first came to light almost a century ago. In 1921, engineers working on a road along Lake Kinneret came upon an ancient mosaic floor which eventually was identified as the floor of a synagogue. The floor—the earliest synagogue mosaic in the country—bears a strong resemblance to mosaics found at nearby Beit Alpha and Tzipori. Remarkably, each mosaic is divided into three distinct panels, with depictions that teach us much about Jewish life at that time. The top-third panel depicts an aron kodesh flanked on both sides by a seven-branch menorah surrounded by the arbah minim (lulav, etrog, hadasim and aravot), a shofar and—an image most people have difficulty identifying—a machteh, or incense pan. These same images, all symbols of the Beit Hamikdash, appear frequently as the chiseled decorations on stones from Talmudic-period synagogues that have been discovered in the Golan Heights. To my mind, the choice of this general motif is a clear indication that the people living in the Galil in those days wanted to emphasize their connection to Jerusalem and the Holy Temple. Our ancestors were incredibly resourceful in preserving and transmitting to succeeding generations the unbreakable link between Am Yisrael and Yerushalayim.

The bottom-third section of the ornate floor differs from those found in Beit Alpha and Tzipori which depict the Akeidah, the Binding of Isaac. The panel in the Hamat Tiberias Synagogue depicts two lions (the symbol of the Tribe of Judah) facing a grid of twelve dedication inscriptions written in Greek.

The central panel is perhaps the most fascinating section. It depicts the twelve signs of the zodiac with a Hebrew inscription for each. In the center is the Greek sun god, Helios. A woman’s face is portrayed in each of the four corners along with a Hebrew inscription indicating the season in the solar calendar (Tishrei, Tevet, Nisan and Tammuz corresponding to fall, winter, spring and summer). This reflects the Jewish calendar, which regularly synchronizes our lunar months with the solar seasons, ensuring that Pesach always falls in the spring.

The top-third panel of the mosaic floor depicts an aron kodesh flanked on both sides by a seven-branch menorah surrounded by the arbah minim (lulav, etrog, hadasim and aravot), a shofar and—an image most people have difficulty identifying—a machteh, or incense pan. The choice of this general motif is a clear indication that the people living in the Galil in those days wanted to emphasize their connection to Jerusalem and the Holy Temple.

Much has been written about this unusual panel, which seems to be a strange departure from Jewish tradition. Depicting human forms? Highlighting mythological gods and astrology? Was this merely accidental or was it a deliberate and conscious choice? The fact that this same zodiac/Helios motif also dominates the center of the Beit Alpha and Tzipori synagogues indicates that the choice of motif in the Hamat Tiberias synagogue was deliberate. The signs of the zodiac are known as “mazalot” and the expression “mazal tov” is extended by Jews all over the world at semachot. Is the inclusion of these signs merely the artistic expression of a non-Jewish artisan? Or could there be a significant religious connection which cries out to be understood? The perplexing mystery of the zodiac mosaic has been the subject of many scholarly articles. I believe that the inclusion of lunar as well as solar themes as the prominent central portion of the mosaic floor is not a coincidence, but rather reflects a deep appreciation of the wonders of the Heavens which was part of the religious philosophy of the time. In addition, the twelve signs of the zodiac could possibly be highlighting a connection with another significant twelve in Jewish thought: the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

The side corridor of the synagogue also contains inscriptions in the floor in both Hebrew and Aramaic in honor of various donors to the “building fund” (some things just haven’t changed!).

What makes this park truly unique is that just a few yards away from the archaeological discoveries is a small stone-enclosed pool where a continuous flow of hot water emerges from the natural hot springs just beneath. The seventeen springs of Hamat Tiberias have been known since antiquity for their curative properties. In fact, pharmacies in Israel keep supplies of mineral salts from these springs.

These springs, whose waters are infused with approximately 100 minerals, were also the subject of many halachic questions dealt with by the rabbis of the Mishnah and Talmud. The rabbis asked questions such as: Is one permitted to cook in Hamat Tiberias on Shabbat? Can one bathe on Shabbat in the hot waters of Hamat Tiberias?

At Hamat Tiberias, rabbinic text comes alive in a dramatic fashion. For the Jews of Tiberias in the third and fourth centuries, the status of this “natural” hot water spring on Shabbat was evidently a practical question.

The park is located on the western shores of Lake Kinneret, right on the main road (Road #60), about one mile south of the modern city of Tiberias, and just beneath the prominent Tomb of Rabbi Meir Baal HaNes. A visit to Hamat Tiberias takes us back to the time after the Churban when, although Jerusalem and the Beit Hamikdash lay in ruins, Jewish life and the spirit of Jerusalem were very much alive and thriving in the Galil.

Peter Abelow is a licensed tour guide and the associate director of Keshet: The Center for Educational Tourism in Israel. Keshet specializes in creating and running inspiring family and group tours that make Israel come alive “Jewishly.” He can be reached at 011.972.2.671.3518 or at peter@keshetisrael.co.il.