Motown’s Orthodox Revival

You would never know Detroit went bankrupt by the looks of two thriving frum communities close to the city. Oak Park and Southfield keep drawing scores of frum families to the area—and it seems like there’s no letting up.

Growth from Within

Shuls and communities must grow organically; in other words, the local Orthodox population must consistently reach out to the unaffiliated as well as to Reform and Conservative Jews. Kiruv is a core component in growing an Orthodox community.

Stephen J. Savitsky

“For us, the depressed economy is actually a blessing; it keeps the cost of living low,” says Rabbi Tzali Freedman of Oak Park, regional director, Central East NCSY. “You could own a beautiful home in a great neighborhood for $150,000. For $350,000, you can get an amazing home.” And what about parnassah? He jokes, “The cost of living is so low in our area, you don’t have to work.”

Micha Zwick, forty-two, a native Detroiter who owns a private investigation agency, sees a “landscape” of employment opportunities in the area. “There are job possibilities, especially for entrepreneurs,” he says. “For those who want to get into real estate, it’s a great market. The metro Detroit area has always had one of the cheapest real estate markets [for a large city] in the country. It became even cheaper with the recession.

“When you turn on the TV, all you see are decrepit homes and neighborhoods [in Detroit],” says Zwick. “[Young couples] come here and are pleased to find well-maintained homes, freshly mowed lawns and friendly faces.”

Frum Detroiters are actually optimistic in the face of the depressed financial environment. “There’s a ‘can-do’ spirit among the business community here,” Zwick reports. “Business owners are very confident about their future and the future of the area, and they are willing to invest in that. We may have hit rock bottom, but we’re coming back.”

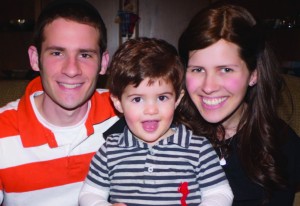

Ariella and Dani Shaffren moved to Southfield in 2012 and bought a seven-bedroom home for under $200,000. The couple is pictured here with their two-and-a-half-year-old son, Koby. Photo courtesy of the Shaffrens

Aside from the low cost of living, the area offers formerly frazzled city dwellers the solace of wide-open spaces and a slower pace of life. “I love that on Sundays, vacation days and Chol Hamoed you could go places without having to factor in four hours [in bumper-to-bumper traffic] for traveling,” says Shira Yechieli, twenty-nine, originally from Queens, New York. “If something is twenty minutes away, it’s really twenty minutes away.”

A community, a family

When God first created the human being, He placed him in the Garden of Eden “to work it and to guard it,” commanded him concerning the fruits and trees of the garden and then declared that “It is not good for the human being to be alone” (Genesis 2:15-18). These verses teach me that every human being requires a purpose or a function, that he must perform that purpose in accordance with certain rules and values and that he cannot accomplish this alone, without a partner or partners. In Freudian terms, the test of the functioning human being is his ability to work and to love, to have a purpose for his being and to enter into responsible relationships of concern and commitment to others. And so God created a family whose task would be to develop the garden, to procreate so that the task could be continued into the future and to perform that task in accordance with a set of rules and ideals. And this first family consisted of man, woman and God.

A community is a family writ large. A Jewish community consists of a group of families dedicated to working together to create a meaningful society, a fragrant and productive garden, united by bonds of love and commitment to God’s dictates. From this perspective, a Jewish community must be a prayer community which links its membership to God; a Torah learning community which enables it to understand what God wants of it and a chesed community which links its members together with bonds of concern for each other’s welfare and joint participation in each other’s joys and sorrows.

Hence the first community I was instrumental in creating, the Lincoln Square Synagogue community, was based on regular meaningful and attractive communal prayer services, communal celebrations of the Sabbath and festivals, regular Torah classes which attempted to teach what God requires of us in our daily lives and an ethos of mutual concern: each member must have a place to eat Shabbat and festival meals and each member’s moments of joy and sorrow are to be shared by all other members of the community. Each member was expected to be involved in chesed, such as adopting an elderly person. We actively got involved in the then-burgeoning Soviet Jewry movement, and these activities were an important sparkplug in developing our synagogue community.

Rabbi Shlomo Riskin

Founding chief rabbi of Efrat, founding rabbi of Lincoln Square Synagogue

Recent residents are finding that the warmth of a close-knit community more than makes up for the Midwest’s brutally cold winters. “The moment we moved here, all of our neighbors came by to say hello, bringing cakes and cookies,” says Yechieli. For several Shabbatot after, she and her family were invited out for meals. “I felt like a celebrity,” says Yechieli.

“Whenever my family comes to visit, they’re amazed that you could stop at a four-way stop sign and people actually let you go if you are the first one there,” she says. “They’re not going to just mow you down. Okay, you can’t get sushi at two in the morning or ten at night, and we have only one pizza shop, but these things become much less of a focus. There’s a simplicity in day-to-day life here.”

Detroit’s newcomers, some of whom were accustomed to having a variety of day schools and shuls, discovered that out-of-town doesn’t necessarily mean out of options. The Oak Park/Southfield communities boast a number of day schools, three kollels and a myriad of synagogues serving approximately 1,000 families. “We’ve got a great product here in Southfield,” says Rabbi Yechiel Morris, rabbi of the Young Israel of Southfield for the past eleven years. He emphasizes the area’s strong Orthodox infrastructure and relatively inexpensive day school tuition—around $8,500 for elementary school.

Over the past few years, dozens of young families have moved to Southfield, says Ariella Shaffren, twenty-seven, a former Teaneck resident who moved to the neighborhood just over a year ago. “We’re all in the same boat; we’re young, we’re moving to a new community with no extended family, but we really feel a part of things,” says Shaffren, who serves as Young Israel of Southfield’s sisterhood president. “People have really taken us in.”

As the population expands, so do the schools. Yeshivas Darchei Torah in Southfield, which runs from preschool to twelfth grade, went from a student population of 330 in 2008 to 373 in 2013.

Ahavas Olam outgrew its current shul space and plans to move to a new building in the spring of 2014.

“My kids are in preschool in Yeshiva Beth Yehudah; since we moved here, the [number of] classes have increased,” says Yechieli. “Each grade added an additional class this school year.” To accommodate its growing student body, the school is in the process of building a new high school and preschool.

Scott Cranis, executive director of Akiva Hebrew Day School, a modern-Orthodox school in Southfield, welcomes the influx of young families moving in from the East Coast. “Our kindergarten enrollment increased by 25 percent in [just] the past six years,” he says.

To prove the shul is serious about building the community, Young Israel of Southfield offers families considering moving to town a $7,500 five-year interest-free loan toward purchasing a home or making renovations.

“We want to show people that we want them to be here,” says Rabbi Morris, who sent representatives to the most recent OU Emerging Communities Fair.

Confident that the community will continue to grow, the shul recently added another youth room, a majestic beit midrash and an outdoor deck and playground. “We got together and said, ‘we can make this happen,’” says Rabbi Morris.

A significant number of frum students move to the Detroit area to attend college at nearby University of Michigan, Wayne State University, Oakland University or Michigan State University; upon graduation, instead of heading back East, many decide to settle in Detroit. “You make connections, relationships with the rav, the shul and the Torah center,” says Gabi Grossbard, forty, president of Ahavas Olam Weingarden Torah Center of Oak Park. “The next thing you know, you feel like a valuable part of the community. People aren’t in a rush to run back to New York where you’re just another person.” (The Ahavas Olam community outgrew its current space and plans to move to a new building in the spring of 2014.)

“It’s not easy getting lost in our community,” Rabbi Michael Cohen, rav of the Young Israel of Oak Park, says. “It’s large, but small enough that people know each other. People like the fact that they see the principal and teachers of their children’s school every Shabbos in shul.”

“They end up staying because they love it,” says Henna Milworn, a native Detroiter who has been hosting an annual end-of-summer barbecue for the newcomers in town as well as for key people “they should meet,” such as school principals and faculty. This year forty-five couples attended, some of whom moved from Lakewood, New York and even Israel. “Everyone was so thankful for the opportunity to meet others in the community and learn about all the resources,” says Milworn. “It’s so unassuming here. There’s no ‘keeping up with the Joneses’; the wealthy live next door to the far less affluent. It’s a great place to raise kids.”

All this, and there’s Torah learning too. “It’s so impressive how the Oak Park community wants to grow spiritually together,” says Erin Stiebel, twenty-seven, who runs the NCSY GIVE Israel summer trip, a five-week chesed program for high school girls. The Stiebels moved to the area in 2012 from Silver Spring, Maryland. “There’s Torah learning everywhere—shiurim, women’s programming, community events. Everyone is so invested in the community’s growth.”

The investment seems to be more than paying off. “Recently, one Friday night we had two shalom zachors,” says Rabbi Morris. “There were years in the past that there weren’t any shalom zachors. Now we’ve got one almost every month. I think we’re creating a model for communities around the country; just bring in a core group, a base of young families and they’ll attract their friends. Detroit is a hidden gem.”

Bayla Sheva Brenner is senior writer in the OU Communications and Marketing Department.

Ed. note: Due to an editing error, the print version of the article on the Metropolitan Detroit community did not include Akiva Hebrew Day School, the 50 year old Zionist Orthodox day school, which has been an integral part of the Jewish community.