The Contributions of the Lubavitcher Rebbe to Torah Scholarship

We live in an age of specialization, which has convinced us that even our greatest leaders excel in only a limited range of activities. It is the rare leader in whom we recognize a wide range of diverse achievements.

Even among gedolei Yisrael in our history, we find some who specialized in halachah, others in pilpul and still others in homiletics, or derush. We have come to believe that those who were involved in community affairs necessarily compromised their scholarly pursuits by doing so. And Chassidic masters who combine their Chassidic Torah with Talmudic expertise are often seen as exceptions to the rule.

Of course, we are all aware of those rare individuals who possessed a dazzlingly diverse repertoire of Jewish leadership attributes. Beginning in medieval times, the Rambam and the Ramban come to mind. In later generations, the Maharal of Prague, the Ba’al HaTanya and the Chatam Sofer are good examples of men who were great Talmudists, heroic community leaders, gifted teachers and preachers and prolific writers.

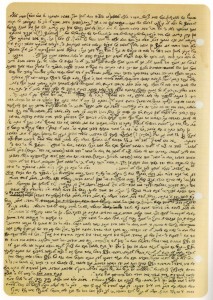

A page of the Reshimot, the handwritten notebooks in which the Rebbe transcribed some of his chiddushei Torah. These notebooks only came to light after the Rebbe’s passing, when they were discovered in a drawer in his room. The entries in these journals date between the years 1928, the year of the Rebbe’s marriage, and 1950, the year of his assumption of the leadership of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement. Throughout these years—which included his evacuation from Berlin in 1933, his escape from Nazi-occupied Paris in 1941 and his subsequent wanderings as a refugee in Vichy France and Fascist Spain—the Rebbe kept these notebooks with him at all times.

The late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, zt”l, whose twentieth yahrtzeit we are commemorating this summer (3 Tammuz/July 1), is an example of one such wide-ranging Torah personality. Sadly, however, many see him much more narrowly, focusing on one or another of his many accomplishments, but failing to appreciate the vast range of his contributions to the machshavah and Torah of the Jewish world.

Because his success in certain areas of leadership is immediately apparent, we tend to blind ourselves to other, perhaps less easily discernible, achievements. Thus, all acknowledge his amazing ability to inspire thousands of his Chassidic followers, as well as many who were not part of his community, to devote their lives to outreach in all the far-flung corners of the globe. His command of the entire corpus of Chassidic thought is evident and impressive, as was his ability to convey those teachings to masses of individuals who have no prior exposure to Chassidic thought.

Rabbi Schneerson’s written works fill multiple library shelves, and his spoken words have been eternalized in audio and video recordings and in many print volumes. His sensitivity, empathy and compassion for all Jews were directly experienced by thousands who had the privilege of individual consultations with him. His care and concern for every Jew—indeed for every human being—were his essential personal characteristics. His counsel was sage, and often bordered on the miraculous. His political views were explicit, forceful and impactful.

Because of all of these phenomenal achievements, and more, many overlook the fact that the Rebbe contributed to traditional Torah exegesis in numerous ways. For the remainder of this essay, I will attempt to describe some of those contributions, while fully aware that my description cannot possibly convey the full scope of his work. I will focus primarily on those aspects of the Rebbe’s scholarly heritage from which I have personally benefited.

Commentary on Rashi

Rashi’s commentary on Chumash is essential to traditional Torah study. Every committed Jew approaches his study of the weekly parashah through the lenses that Rashi provides. Over the centuries, a number of Torah scholars of the first rank have written commentaries on Rashi’s commentary. Such works are known as “supercommentaries.”

The Rebbe left us with a modern-day such supercommentary synopsized by a team of scholars in the form of a readily available five-volume work entitled Biurim LePirush Rashi al HaTorah. This work originated from the Rebbe’s practice of delving into a quotation from Rashi at each of his regular public, multi-hour farbrengen. He attended to issues of textual content, grammar or sequence. The Rebbe would first resolve those issues before continuing to expound upon the subject from a Chassidic, and sometimes musar, perspective. His five-volume work dispenses with the Chassidic material and distills much of the Rebbe’s teachings of what we would call the peshat, or simple meaning of Rashi’s words.

The Rebbe paid careful attention to seemingly minor points in the text. By concentrating on those fine details, he was able to extract an array of exegetical treasures. Some of his conclusions have halachic implications, some are keen observations of the linguistic components of Rashi’s choice of words and all are relevant to the personal spiritual service of the reader. I myself have come to rely upon this work in the preparation of my weekly sermons and as material for discussion around the Shabbos table, irrespective of whether those around the table are learned elders or young schoolchildren.

The Works of Rambam

The Rebbe expected from his followers a great deal in the way of Torah study. He strongly reinforced the study regimens that his distinguished predecessors instituted: a requirement of one masechet of Shas annually, a daily diet of Chassidic discourses and daily portions of Chumash, Psalms and the Chassidic classic Sefer HaTanya. The Rebbe emphasized that this was all in addition to the individual learning required of each person according to Jewish law, as depicted in the Shulchan Aruch’s Hilchot Talmud Torah. Among the Rebbe’s own innovative projects in this regard was his request for the daily study of Rambam. For more advanced students, he required the study of three chapters or, if too difficult, then one chapter daily of Mishneh Torah; for those less knowledgeable, he required the study of a parallel selection of the Rambam’s Sefer HaMitzvot each day. The festive siyum with which the completion of the entire work was celebrated each year was rivaled only by the festivities of the major holidays on the Jewish calendar.

His counsel was sage, and often bordered upon the miraculous. His political views were explicit, forceful and impactful.

But the Rebbe’s emphasis on the Rambam and his teachings did not stop with his insistence upon the study of the Maimonidean text itself. Entire volumes of the Rebbe’s teachings are dedicated to analysis of those texts. My personal favorite remains his commentary on the Rambam’s Hilchot Beit HaBechirah, the Laws of the Holy Temple. The Rebbe recommended that Hilchot Beit HaBechirah be studied during the Three Weeks of mourning prior to Tishah B’Av. In his commentary, the Rebbe combines a profound analysis of the conceptual underpinnings of the Rambam’s text with an appreciation for the spiritual guidance that the student can derive from the Rambam’s treatment of the subject. He achieves the latter by applying his mastery of Chassidic thought to the Rambam’s words. But for the former, he relies upon a surprising “mentor”: the brilliant but often cryptic notes of Rabbi Yosef Rosen, known as the Rogatchover Gaon.

It is clear that the Rebbe was heavily influenced in his approach to Talmud study in general, and to the works of the Rambam in particular, by this early twentieth-century genius. The hallmarks of the Rogatchover’s approach are his astonishing bekiut (thorough familiarity with the entire range of rabbinic literature) and a method of study that does not hesitate to use abstract philosophical concepts. Garnered in part from the Rambam’s own Moreh Nevuchim, Rabbi Yosef Rosen uses these concepts as analytic tools to find the underlying themes behind seemingly disparate strands of Talmudic discussion.

In my opinion, the Rebbe remains the foremost interpreter of the Rogatchover’s Torah teachings. Most of us, who find the Rogatchover’s writings forbiddingly terse and often inscrutable, are indebted to the Rebbe for making them more accessible.

Chiddushei Torah and Lomdut

The ultimate criterion of rabbinic greatness is, of course, exceptional proficiency in the Talmud corpus. The ability to formulate novellae, to expound with originality upon a wide range of texts—reconciling seeming contradictions and resolving questions of all sorts—is the sine qua non of rabbinic greatness. It is here that the Rebbe’s contributions, although published and available to all, are least known to those outside his circle of followers.

The most incontrovertible demonstration of the Rebbe’s lomdut is found in the hadranim, the lectures he delivered at the conclusion of studying Talmudic tractates. The Rebbe delivered 151 such hadranim, eighty-four of which are recorded in the two-volume Hadranim al HaShas, published by Kehot Publication Society. I have two personal favorites: one is the hadran that the Rebbe delivered on the occasion of the completion of the entire Talmud, in which he persuasively argues that a common thread runs through all of the hundreds of disputes between Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai. The other is his hadran on the tractate Bava Kama. This is a tour de force in which the Rebbe connects the Bavli and Yerushalmi, uses the “Brisker” concepts of cheftza and gavra and ingeniously links the beginning of the tractate with its end—all to elucidate a fundamental principle which underlies the entire 118 folio pages of the crucial tractate.

Derush, or Homiletics

As a pulpit rabbi for many years, and as one who is still frequently called upon to deliver sermons, I have found the Rebbe’s works to be veritable archives of chomer lederush, homiletic material. The thirty-nine volumes of his selected edited sichot, or weekly discourses, and more than two hundred unedited ones, might prove to be too overwhelming a source for busy pulpit rabbis. Fortunately, many of his teachings have been condensed and compiled in a collection about the festivals called Shaarei HaMoadim. I have found those volumes indispensable for preparing and delivering inspiring and spiritually relevant sermons—grounded in a heterogeneous array of sources—to audiences of every possible background. On the occasion of Shevii Shel Pesach, I once delivered a lecture to a distinctly secular audience on the topic of miracles, using the Rebbe’s discourse on the Splitting of the Red Sea from Shaarei HaMoadim as a guide.

The Rebbe as Pastoral Counselor

Most readers would surely concur that an essential component of great Torah scholarship is a rabbi’s ability to use that scholarship to assist those seeking personal guidance. We have interesting manuscript evidence of the Rambam’s skill in this regard; in much more recent times we know of the practical advice that spiritual leaders like the Chofetz Chaim and the Chazon Ish were able to give those who sought their counsel.

I personally benefited from the Rebbe’s advice in a life-changing telephone conversation I had with him more than forty years ago. Thousands of others have benefitted similarly.

We have written documentation of these counseling sessions in the multi-volume collection of letters that the Rebbe wrote over the course of his leadership career. This collection is published as Iggerot Kodesh. It amounts to thirty volumes and has scores more in the works. I am drawn to this collection especially because of my training and experience in the field of psychotherapy. A number of major principles of effective counseling emerge from these letters. To name a few:

1. It is important to have clear and achievable goals in life.

2. When those goals are reached, one must immediately set new goals and never complacently rest upon one’s laurels.

3. Study, joy and song are antidotes to depression, as is focusing on helping others.

4. One must cultivate as many friendships as possible, and do so by giving spiritually or materially to the other person.

5. We need much less sleep than we think.

6. One must persist in the face of failure. Failure is seldom total and never final; it is usually a step toward reaching the next level of achievement.

7. One must never compromise one’s religious principles. Such compromise is not effective.

8. Each person has a distinct role to play; both God and one’s fellow man fully rely on him to accomplish it. No one else can do what he is uniquely created to do.

The Rebbe tried valiantly to change the orientation of modern psychology from Dr. Sigmund Freud’s approach to that of Dr. Viktor Frankl, author of Man’s Search for Meaning. (Dr. Freud and his followers believed that unconscious and dark forces were the essence of man. Dr. Frankl, who was a survivor of Auschwitz, asserted that man’s conscious search for meaning is his essence. The Rebbe personally encouraged Dr. Frankl to persist in his dispute against the Freudians. See Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks’ article on page 21.)

By expanding our view of the Rebbe and increasing our familiarity with his contributions, we get a picture of his unusual significance in Jewish history. More important, we become aware that his teachings remain a vital source of education and inspiration for all Jews, irrespective of one’s background and hashkafic perspective.

The Rebbe was not just a rebbe for Chabad Chassidim. He was, and remains, a rebbe for us all.

Listen to Rabbi Tzvi Hersh Weinreb discuss the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s scholarship at www.ou.org/life/inspiration/savitsky-weinreb/.

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb is executive vice president, emeritus of the Orthodox Union.

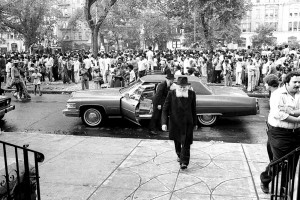

Photos courtesy of Jewish Educational Media’s (JEM) Living Archive. JEM is devoted to gathering, preserving and providing access to the photos and audio and video tapes of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. JEM has also embarked on an oral history project about the Rebbe’s life, documenting first-person accounts of people’s encounters with the Rebbe, as well as tracking down and preserving priceless documents from the Rebbe’s largely unknown early life.