Daniel Renna

If you happen to be flying over the city of Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, you may be surprised to spot a lone kippa among the kufis. It’s sure to be Daniel Renna’s. As the representative of the US Department of State for International Affairs, Renna’s gotten used to being a stranger in a strange land. He’s been at it for nearly ten years.

While serving at US embassies in Slovakia, The Gambia, Armenia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and visiting with Jewish communities accross the globe, Renna, thirty-seven, has learned to converse in various languages and wear many hats. He’s arranged for visas, pulled visiting American citizens out of jams, and taught a course in American popular

culture at an Armenian university.

Renna’s primary responsibilities as a Foreign Service officer are to represent the US government and its interests, to meet with foreign government officials, and to review the political climate in the country in which he is based and then relay his findings back to Washington.

“In many ways, I’m like a journalist,” he says. “I have a very specific audience– key policymakers in Washington. I am the State Department’s eyes and ears on the ground.”

Renna says he ferrets out the needed information and encapsulates it in a form the policymakers “can easily digest” in order to make informed decisions. He also follows the particular country’s economic trends, and tries to advance commerce between local businesses and the US. He does all of this, and also layns the parashah in places where no one else can.

A native of New Jersey, Renna experienced his first taste of international affairs back in high school while on an NCSY trip to the former Soviet Union to meet with refuseniks. He was so excited about the trip, he spent three months teaching himself how to speak Russian.

After graduating from Yeshiva University, he decided to pursue a master’s in international affairs at George Washington University in Washington, DC. Renna’s first post in Bratislava, Slovakia, turned out to be “a clear act of hashgachah pratit.” Shavuot that year fell a week after he arrived and the one woman davening on the other side of the shul’s mechitzah was his wife-tobe, Adela.

“The fifty people in my diplomatic class listed the top fifteen places they preferred going to,” he says. “While Slovakia was number one on a lot of other people’s lists, it was number seven on mine. In the end, I got chosen [to go there] . . . a big surprise to me.”

A pleasant one at that; he no longer had to travel the world by himself.

Emulating Avraham

Throughout their travels (each assignment requires a stay of two to three years), Renna and his wife have also generated many powerful moments in the lives of both Jews and non-Jews.

“We were very conscious of the fact that we had a great opportunity the mekadesh Shem Shamayim,” says Renna. “If you live in a place where it is easy to be Jewish, you roll out of bed and there’s always a minyan avail-able, a kosher restaurant . . . and then you live in the middle of nowhere, you realize what it is to be the Ohr L’Goyim type of person. I go out and represent the US; at the same time I represent Jews and the idea that you can be frum and do this.”

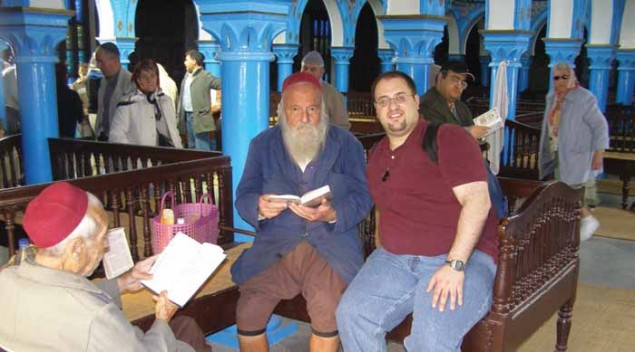

Daniel Renna, who works for the US State Department, with some of the elderly men who spend their days learning in the Hara Kabira shul in Jerba, Tunisia.

Daniel Renna, who works for the US State Department, with some of the elderly men who spend their days learning in the Hara Kabira shul in Jerba, Tunisia.

In 2003, while on assignment in Banjul, The Gambia, a country comprised predominantly of Muslims and a smattering of other faiths, the Rennas had a real opportunity to make a kiddush Hashem. “I walk around with a yarmulke all the time,” he says. “The [Gambians] couldn’t reach me on Shabbos. I would go out to lunch with people and I wouldn’t eat. They noticed.”

According to Renna, the Gambian natives had no idea what Jews were. He once attended a dinner at the home of the US ambassador to The Gambia where the guests were breaking the Fast of Ramadan. The imam of a mosque in Serrekunda asked him what religion he practiced. “When I told him, he responded, ‘Fortunate is the day I have met a Jew!’” says Renna.

Renna also took part in a monthly public diplomacy event involving Christians, Muslims and Bahia religious leaders. The group invited him to speak about Judaism.

“I discussed the concept of tzelem Elokim,” he says, “that Avraham represented the prototypical person, one who recognized his Creator and emulated the concept of human dignity. He spread the message that every person has a direct relationship with HaKadosh Baruch Hu.” The message resonated with the audience; in fact, Gambian television broadcasted Renna’s presentation during the “Muslim hour” and the “Christian hour.”

“I go out and represent the US; at the same time I represent Jews and the idea that you can be frum and do this.”

“I was very conscious that I was representing what a frum Jew is,” says Renna. “My being able to converse . . . and quote Scripture was very impressive to them. They saw a Jew actually doing what a Jew is supposed to do— following the word of God.”

“One of the ways [you can show] you are a decent person is . . . paying workers on time, at a fair wage,” says Renna. “We’ve employed domestic staff and gardeners [in the various places we’ve lived] who appreciate this and say, ‘Ah, this is what a Jew does.’” ‘

Renna reports that every time Adela pays the gardener for his work, he actually breaks down and cries. He connects to the idea that “we, as Jews, respect him as a person and as a tzelem Elokim.”

I Left My Appendix in Armenia

In April 2009, a week before Renna left Armenia for his current post as deputy political counselor at the US Embassy in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, he suffered an appendicitis attack. He returned home after a four-day hospital stay, and looked forward to attending shul for his last Shabbat there. However, it was close to 104 degrees outside and his wife wasn’t about to let him walk to shul in his post-operative condition. She suggested that the shul come to them and they would host the kiddush. The rabbi brought over talleisim and siddurim along with a handful of congregants, most of whom had endured four decades of Communism. Renna layned the parashah for the congregants for the last time. “They told us our presence [in the country] was such a ‘light’ for them,” he says.

Renna toveyling dishes in the Atlantic Ocean while stationed in The Gambia.

Renna toveyling dishes in the Atlantic Ocean while stationed in The Gambia.

Photos courtesy of Daniel Renna

Renna calls his current post in the Congo “Boro Park compared to the other places.” He explains that the country is rich in gold, precious metals and diamonds, and Jews have been dealing in raw diamonds in the area for a long time. He also discovered a store in the area owned by a Satmar Chassid living in Antwerp, who sells kosher wine and kosher meat from New York. “We all get together for Shabbos, all thirty of us, from Israel, Belgium, France, and the US hosted by the Chabad shaliach, who’s been here for twenty years.”

Although Renna loves traveling and “seeing the world with always something new to explore,” living so far from friends and family can prove challenging. He’s grateful for the frequent Internet contact.

“I don’t know how people did this job without it [the Internet],” says Renna. “I would love to keep doing this, to go to interesting places and meet fascinating people . . . maybe one day become an ambassador.”

Renna’s job at the US embassies– institutions he calls “microcosms of the United States”–brings him into contact with people from a variety of backgrounds– some who, before meeting him, have had zero contact with Jews.

“People are sometimes uneasy when they find out an Orthodox Jew is [working at the embassy],” he says. “They are not sure what to expect and are pleasantly surprised after spending two years with us.” In Yerevan, Armenia, Adela gave a cooking class to a group of embassy employees, introducing them to the joys of baking challah,while explaining its significance in a Jew’s life.

Adela says, “I hoped to plant seeds of experience that will help foreigners [and] Americans relate to other Jews they may encounter in the future.”

Bayla Sheva Brenner is senior writer in the OU Communications and Marketing Department.