On Complexity and Clarity

By: Shalom Carmy

When asked what he had learned at Harvard, Rav Aharon Lichtenstein, zt”l, answered that there he grasped the complexity of human beings and their affairs.

Rav Lichtenstein, like the Rav, understood that many human challenges, and precisely the most important ones, enact the clash of competing, even conflicting, values, all of which have legitimacy. As a practical matter, we can’t avoid giving preference to one ideal over others; we are compelled to choose among people and causes that claim our allegiance. Nevertheless, if you are honest, you cannot deny or dismiss the spiritual reality of the “road not taken.” You must continue to keep in mind, and respond to, reality in its full complexity.

Some refuse to admit to irresolvable conflict; life is simpler with clear-cut marching orders and one-dimensional emotional attitudes. In their opinion, when God commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son, then, because he must obey God, he should ideally have suppressed his natural feelings for his son. A father’s feelings, though valuable in ordinary life, must be obliterated by the higher duty. Such people believe that the ideal Abraham–as Rav Lichtenstein once put it–would slaughter his son with the same equanimity that he would shake a lulav on Sukkot. Rav Lichtenstein did not want to be such a person, nor did he educate others to think that way. Consequently, his vision of Abraham was of a man wholly committed to obeying God, even as he did not abandon or diminish in any way his devotion to his son.

This insight itself is invaluable. Yet most of us, even having digested it as a philosophical thesis, fall short of living it consistently. We act one way or another or we arrive at some middle ground, and the compromise then becomes the new equilibrium. Afterward we offer lip service to the options not actualized, but their vitality, in effect, has been neutralized.

Rav Lichtenstein never allowed that to happen. In that respect, as in others, he remained young to the end. Partly, you say, this was a triumph of the intellect: his comprehensive insight refreshing and sustaining the radically complex awareness. No doubt, the sweep and scope of Rav Lichtenstein’s knowledge of Torah, the perspicuity of his insight into the human condition and the power to articulate that perception that he gained from his liberal arts studies, enabled him to bear in mind considerations invisible to, or easily neglected and forgotten by, most of us.

But this is not the whole story. Avodat Hashem is not just refined intellect, but intellect harnessed by the human being in his or her wholeness and wholesomeness.

I recall the time, in the late sixties, that Rav Lichtenstein arranged a sunrise Shacharit for his students, followed by an early shiur. He then accompanied us to the Isaiah Wall, where we demonstrated against the massacres in Biafra. As we trudged around on that bitterly cold morning, one of us asked: “Rebbi, if we ought to have early shiur today, why not conduct a march every day?” Rav Lichtenstein did not answer.

One reason we fall short of living according to our best insight is that we spend too much time living our spiritual lives under the gaze of others.

I ventured to suggest that if we violated our normal schedule regularly, the study of Torah would soon fall by the wayside. Maintaining the set schedule with one exception, I thought, was a reasonable compromise between the ongoing commitment to Torah and oneís duty not to ignore a genocidal war. Rav Lichtenstein said nothing; he neither endorsed my suggestion nor criticized it. I learned that sometimes it is more honest to let a question remain unanswered than to be satisfied with a reassuring but not wholly adequate solution.

Rav Lichtenstein subscribed to Rabbi Soloveitchik’s view that territorial compromise in the land of Israel, however painful–he compared it to amputating a limb to save a life–is permissible for the sake of peace. During the Gaza disengagement, he vigorously opposed soldiers disobeying orders. Even if the government’s policy was ill-advised, to undermine the stability of Israel’s political system was more harmful. Many adopted his conclusions and gave no further thought to the subject. For Rav Lichtenstein, however, the sense of pain regarding every dunam of retreat was real, as was his sympathy for the settlers being uprooted. It was so real that he went down to Kfar Darom, without publicity, to spend the last hours before the evacuation with them. By then he was an old man, and his views were not popular in those circles. And yet his sympathy did not end with words. He found a way to translate it into action.

I said “without publicity”: One reason we fall short of living according to our best insight is that we spend too much time living our spiritual lives under the gaze of others. In the sixties, Rav Lichtenstein was invited to speak on ethics at an RCA convention. In the wake of a recent scandal in Albany, a prestigious newspaper hinted that a timely remark could gain the young rabbi a bit of celebrity. Rav Lichtenstein told us that he had made sure his speech included nothing that would stimulate extraneous interest. So his presentation did not make news worthy of printing, and he forfeited his shot at glory. How starkly does this contrast with the “look-at-me” mentality that too often trumpets today’s self-nominated moral and religious idealists.

There is a common belief that sensitivity to complexity leads to indecision. We see that Rav Lichtenstein found ways to respond creatively, authentically and courageously when action was appropriate. An appreciation of complexity (murkavut) is not the same as needless complication (histabechut). To the contrary, intellectual clarity dispels the mental clutter that obstructs decisiveness and clouds judgment. When asked how to balance the tzedakah needs of Israeli institutions vs. local American causes, Rav Lichtenstein noted that cutting down on luxury vacations might leave ample money for both. In the eulogy I gave on the day of his funeral, I mentioned his help in clarifying my own crucial choices. Such examples can be multiplied indefinitely.1

As he grew older, Rav Lichtenstein avowed, his sense of the need for what a liberal arts education can offer sharpened, although he was less sure whether it was obtainable today in mainstream academia; if not, he said, with characteristic candor, one must gain an education on one’s own. But he spoke of an increased “awareness of the difficulties of realizing it; of the very considerable spiritual and educational cost–regrettably far in excess of what is inexorably necessary–which the proponents of Torah u’Madda often pay for their choice.”2 Much of the unnecessary cost can be attributed to wrong priorities. If the Modern Orthodox were settling for mediocrity in Torah, he ruefully quipped, it is not because they were burning the midnight oil poring over Plato and Milton.

If the Modern Orthodox were settling for mediocrity in Torah, he ruefully quipped, it is not because they were burning the midnight oil poring over Plato and Milton.

As I grow older, I realize how much Rav Lichtenstein prized stability of character (yatzivut) and persistence. I don’t mean only hard work and dedication, but also steadiness of purpose and outlook. What differentiates those who succeed in integrating general studies and exposure to the world with the primacy of Torah is often the strength of fundamental convictions.3 It means not being swayed by passing moods, not rushing to get on board with the latest social and political discovery or novel intellectual trend, not measuring one’s stature and creativity by the number of traditional teachings one is able to doubt while standing on one foot. Here too Rav Lichtenstein’s teachings and example, his genuine breadth and remarkably conscientious thoroughness, are a standing rebuke to much of what passes for “enlightened” discourse.

Voices were raised in the late 1960s when Rav Lichtenstein decided to add a hashkafah shiur. One Talmud-focused student complained that it was over everyone’s head. Rav Lichtenstein responded, paraphrasing Rav Yitzchak Hutner, rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin: “The best teaching aims at where the student will be years later rather than at his present state.”4

The years have passed, over forty-five years, and now the sheloshim too are over. Whether Rav Lichtenstein’s thought and expression ever caught up with that student, I don’t know. I know that I and thousands of other talmidim are still progressing toward the ideals of character and the ideals of Torah study that he set for us. We commemorate his mastery of Torah and his capacity to draw judiciously and elegantly on the Western intellectual tradition to enhance authentic and critical religious thinking. We dwell on his ethical greatness and the magnificence of his piety–how he prayed, how he listened to other human beings, how he attended to his father, how he never wasted a moment. This man, who made every effort to avoid placing himself on a higher level than others, who demonstrated enjoying the best that a “normal” life can offer with unmitigated zest while pursuing without compromise or abatement the passionate service of his Creator, continues to beckon from eternity, toward eternity.

Notes

1. Available on Yeshivat Har Etzion’s web site and elsewhere.

2. See also my “Music of the Left Hand: Personal Notes on the Place of Liberal Arts Education in the Teachings of R. Aharon Lichtenstein,” Tradition 47:4 (winter 2015).

3. See also my “The Gate Matches the Home: On R. Lichtenstein’s Depiction of Faith,” Tradition 47:4 (winter 2015).

4. See Pachad Yitzchak: Iggerot no. 155.

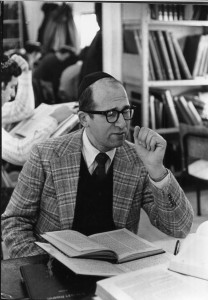

Rabbi Shalom Carmy is co-chair of the Jewish Studies Executive at Yeshiva College of Yeshiva University and editor of Tradition, the journal of the Rabbinical Council of America.