Rick Hodes

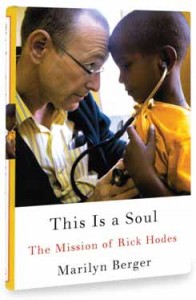

Dr. Rick Hodes, an Orthodox Jew who lives in Addis Abeba, examines a young Ethiopian boy. Courtesy of JDC

Dr. Rick Hodes, an Orthodox Jew who lives in Addis Abeba, examines a young Ethiopian boy. Courtesy of JDC

From outside, the medical clinic of the Mother Teresa mission in Addis Abeba looks like a rundown warehouse, a block-long concrete building with crumbling walls. Inside, it looks like an emergency Red Cross shelter set up in a dank high school gym, with rows of blanket-covered young men lying on canvas cots.

On the rainy morning I visited the clinic in the capital of Ethiopia about a decade ago, the only signs of activity inside the crowded room were nuns scurrying around. Among the cots walked an American man, outfitted in a checkered cotton shirt, blue jeans and a baseball cap, a stethoscope around his neck. For a few hours, Dr. Rick Hodes walked from cot to cot, consulting with the nuns in self-taught Amharic, checking the condition of each patient, taking pulses, listening to breathing and squeezing folds of skin to detect dehydration.

“It doesn’t matter what religion he is; he is doing this for humanity.”

Hodes, a native of Syosset, Long Island, who studied medicine at the University of Rochester and Johns Hopkins University and studied Judaism as a ba’al teshuvah at Aish Ha- Torah in Jerusalem, has worked full-time in Ethiopia, one of the world’s poorest countries. Since 1990, Hodes has served as medical director for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC or the Joint). Over the years, he treated the Ethiopian Jews who eventually made aliyah. Then, the Falash Mura, Ethiopians from Jewish backgrounds whose ancestors had converted to Christianity, and in recent years, have attempted to return to the Jewish fold. Then, everyone.

Hodes started making rounds at the Mother Teresa mission in his spare time shortly after he came to Ethiopia. Now, since most of the Ethiopians with Jewish roots have left for Israel, and the Joint’s clinic in the capital has closed, he’s still there; a full-time Joint employee as part of the organization’s non-sectarian outreach.

He spends much of his time in Addis Abeba at the mission, and flyingup north to the Joint’s remaining clinic in Gondar that serves the 9,000 Falash Mura awaiting aliyah, who are listed by Israel’s Ministry of the Interior. That’s when he’s not patrolling the streets, looking for ill people, Christians and Muslims, to treat.

“It doesn’t matter what religion he is; he is doing this for humanity,” Monica Thonen-Bartet, a Maltese volunteer at the Addis Abeba mission, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “This is the most beautiful man I have ever seen.”

In Ethiopia, he’s known as “Dr. Rick” or “Dr. Musa” (his Hebrew name is Moshe). In medical circles, Hodes, fifty-four, is known as an expert on exotic diseases, editor of the Ethiopian edition of Where There Is No Doctor: A Village Health Care Handbook. In Jewish circles, he is known as the Orthodox Jew who is trying to save his small corner of the world.

Hodes, who is not married and has no children, keeps in regular touch by phone with his mother back in the US. He has been the subject of countless newspaper stories and a few documentaries focusing on his selflessness and religious observance, the Shabbat meals to which he invites Jewish visitors and interested non- Jews, the young Ethiopians he has adopted and taken into his rented Addis Abeba home, the score of indigent patients for whom he has arranged treatment in the West, the times he has gone to places like Albania and Tanzania and Bangladesh during medical emergencies. CNN named him a finalist in its 2007 Heroes competition; ABC, a “Person of the Week.” Most recently, he was the subject of Marilyn Berger’s This Is a Soul: The Mission of Rick Hodes, a biography that paints him as humanitarian if not outright saint.

Marilyn Berger’s This Is a Soul: The Mission of Rick Hodes tells the uplifting story of a frum American doctor who has spent nearly three decades caring for the poor and sick in Africa.

Marilyn Berger’s This Is a Soul: The Mission of Rick Hodes tells the uplifting story of a frum American doctor who has spent nearly three decades caring for the poor and sick in Africa.

Small and wiry, a dedicated jogger, Hodes is quiet by nature, warmed up by strangers who need medical chesed. Kids swarm around him. During my few days with Hodes in Ethiopia, where he served as my host, I accompanied him to the still-open Joint clinics and the Mother Teresa mission. I watched him bantering with adults and playing with children. He’d place his stethoscope around the kids’ necks and show them how to listen to his heartbeat. The doctor-patient relationship reversed, even the shiest kid would warm up.

I tried to get a reading of Hodes. I told him how I had first heard of his good works several years earlier, in Israel. “A lot of people think you’re a saint,” I said, while we were walking through a rocky field. Hodes stopped walking. “I’m not a saint,” he snapped.He was annoyed by the statement.

“Albert Schweitzer,” the late NobelPeace Prize-winning medical missionary, “is really a hero,” Hodes said. “Schweitzer got on a boat and didn’t know whether he was going to get off two weeks later. I get on KLM and after two meals and movie, get off the plane and complain that I’m jet lagged. So Albert Schweitzer is a high-level guy.”

Hodes sees hashgachah pratit in his lifework; he notices the hand of God in seemingly chance encounters that, he says, are how he gets worldrenowned specialists to sponsor free medical treatment that ordinarily would cost thousands of dollars. He tells a story that took place at a Minneapolis- area synagogue: he had stopped there for Shacharit and made serendipitous connections that resulted in a pair of lifesaving, free surgeries for patients who had massive tumors other doctors had considered inoperable.

One of Hodes’ patients, a Muslim named Merdya Abdisa, had an orange- sized tumor removed from her eye at a Catholic hospital in St. Paul by the Orthodox Jewish doctor Hodes met at shul, Eric Nussbaum. Dr. Nussbaum also operated on a man known simply as Dawit, who had a seven-and-a-half-pound tumor growing out of his forehead. Today Dawit is free of the tumor and is back in Ethiopia getting chemotherapy.

Berger’s book tells of the day Hodes davened Minchah, in full view of the patients, in the corner of a government hospital in Tanzania, while volunteering during a refugee crisis.

“What country is he from?” one onlooker asked.

“He is an Israeli person, a Jew,” Hodes’ translator answered.

After finishing his prayers, Hodes turned to the translator: “Tell them I was praying for their health.”

“I didn’t know Israelis pray for non- Israeli people,” the translator said. “Of course we do,” Hodes said.

Another day, some refugees asked Hodes what it means to be Jewish. Al regel achat, he explained, “The Jewish people were asked by God to be examples to the world of three things: honesty, morality and kindness. That is the point.” The next day five young refugees asked to see him. “Their demeanor,” Berger writes, was “very much like the one they would adopt when they are about to report a death.”

“We agree,” one of the young men told Hodes.

“Agree to what?” Hodes asked, baffled.

In all earnestness, they replied, “We want to join the Jewish people.”

Steve Lipman is a staff writer for the Jewish Week in New York.