Torah Judaism Is Alive in Germany: Q & A With Rabbi Josh Spinner

Which country boasts some of the fastest-growing Jewish communities in the world, outside of Israel?

Surprisingly, it’s Germany.

Who would have predicted that some 120,000 Jews would settle in Germany, with more than 20,000 residing in its capital? Even more astounding, Torah Judaism is on the rise in Germany, with a thriving Orthodox community of more than sixty young families in Berlin. The frum community in the country’s capital is growing so rapidly that parents rush to register their children in the Jewish-run nursery school soon after birth in order to ensure their placement. Opened five years ago with just twelve students, the nursery school today enrolls sixty-three students, and plans are in the works for building a facility to accommodate 120 children.

Since the fall of the USSR in 1989, thousands of Jewish émigrés from the former Soviet Union resettled in Germany, lured by generous resettlement packages. Aware of its responsibility to atone for the Holocaust, the German government offered Jewish immigrants numerous benefits including medical care, language lessons, job training and free education for children from elementary school through university. Ambassador Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress and a noted business leader and philanthropist, saw this influx as an opportunity to spark a commitment to Judaism in a population long divorced from Torah.

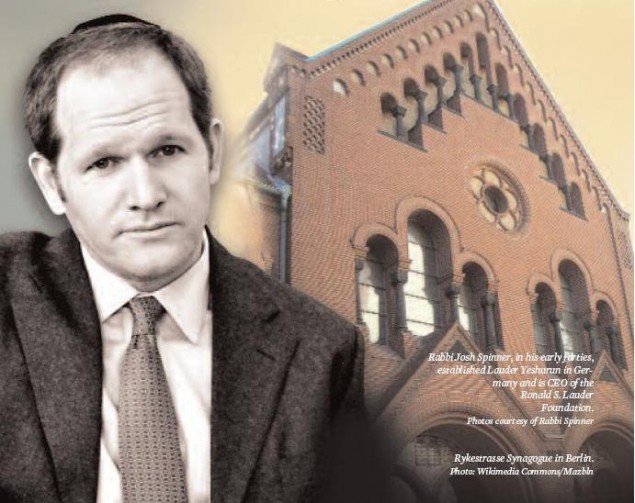

In 1997, Mr. Lauder enlisted Rabbi Josh Spinner for the job. He did not disappoint. Reaching out to this new generation of immigrants, Rabbi Spinner established a set of programs and institutions that today comprise Lauder Yeshurun, the leading Jewish outreach organization in Germany.

An unassuming man in his early forties and a formidable powerhouse of ideas and energy, Rabbi Spinner was born in the United States and studied at yeshivot in Toronto and Jerusalem. He also earned a BA from Columbia University in New York City. After devoting two years to outreach in Minsk, Belarus, he returned to New York to learn at Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem, where he received semichah in 2000. Shortly afterward, he moved to Berlin and established Lauder Yeshurun, the engine behind the remarkable resurgence of Torah in Germany.

The heart and soul of Lauder Yeshurun are Yeshivas Beis Zion and the Midrasha. Amazingly, while the Berlin-based yeshivah attracts young men with little or no Jewish knowledge, it transforms them into first-rate talmidei chachamim. The Midrasha, a comparable institution for women, brings Jewish women back to their roots, giving them the knowledge and the foundation to build strong religious homes. In recent years, the Midrasha relocated to Berlin from Frankfurt am Main to be closer to the yeshivah. Now, with each passing year, there are more and more weddings of alumni to celebrate. Each new couple is a tremendous source of pride for Rabbi Spinner, who today serves as CEO of the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation.

These young religious couples not only form the nucleus of the frum kehillah in Berlin, they are the catalysts for change throughout the country. A kindergarten and primary school are now part of the Lauder Yeshurun empire, as is Kollel Tiferes Yechezkel, named in memory of Rabbi Chaskel Besser of New York, one of the founders of Daf Yomi in the US.

Rabbi Spinner is also behind the reestablishment of the Rabbinerseminar zu Berlin, the legendary rabbinical seminary founded by Rabbi Dr. Azriel Hildesheimer. From 1873 until its closure the morning after Kristallnacht in 1938, “Hildesheimers,” as it was popularly referred to, trained rabbis for the Jewish communities of Germany and Western Europe. Since the reestablishment of Hildesheimers in 2009 under the direction of Dayan Chanoch Ehrentreu of London, eight young men have earned semichah and currently serve as rabbis and educators throughout Germany.

Meanwhile, outreach in the country continues unabated. Kiruv centers now exist throughout Northern and Eastern Germany, providing vital outreach to university students in Berlin, Leipzig and Hamburg. Jewish students from Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, Russia and other countries flock to Lauder Yeshurun as well.

Lauder Yeshurun serves as a beacon of light in Central Europe, drawing new generations of Jews closer to their birthright and their rightful heritage.

Rabbi Spinner, his wife, Joelle, and their three children are the proud pioneers of this burgeoning Jewish renaissance. “However,” Rabbi Spinner cautions, “satisfaction breeds complacency.” The work continues.

Bayla Sheva Brenner Speaks with Rabbi Joshua Spinner

Jewish Action: How did you become involved in kiruv?

In1987, Ronald Lauder established the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation, committed to rebuilding Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe where the destruction of the Holocaust followed by the oppression of Communist rule led many Jews to become disconnected from their heritage. The Lauder Foundation seeks to reunite these Jews, many of whom know nothing about Judaism, with their latent, but not forgotten, Jewish identity.

Providing Jewish education is a primary goal of the Lauder Foundation. It believes that the children will bring Judaism home to their parents, the lost generation that was deprived of its heritage.

The Lauder Foundation currently operates in Austria, Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Poland, Russia, Ukraine and other countries throughout Central and Eastern Europe.

For more information, visit http://www.lauderfoundation.com/.

Rabbi Josh Spinner: In 1995, after spending a year post-college learning in a yeshivah in Yerushalayim, I thought that I should also give a year back to Klal Yisrael. I signed up with YUSSR [Yeshiva University Students for Spiritual Revival in the former Soviet Union], an outreach program for teens in Belarus, Russia and the Ukraine. I ended up staying two years in Belarus.

The experience was life transforming. My first Shabbos home in New York after two years of making Shabbos for dozens of kids in Minsk, I sat around the table with some friends and realized that the only person for whom I had ensured there would be Shabbos that week was me. Why would I make Shabbos happen only for myself, I thought, if I could make Shabbos happen for others as well? I realized that I wanted to do something of importance for Klal Yisrael, and the best way of ensuring that it was of importance was that it would not happen without me.

JA: What led to your involvement with the Lauder Foundation?

RS: I met Ronald Lauder “by chance” in a hotel in Warsaw in 1997. He asked what my plans were after YUSSR. I said I’m going to law school. He replied, “You think you could leave what you are doing and just become a lawyer?” I told him I had to get a job. Soon after I returned to Minsk, I got a phone call from Mr. Lauder’s office. He wanted to see me in New York that Thursday and had already arranged a plane ticket. He asked me what it would take to convince me not to go to law school and instead work for his foundation.

I heard Mr. Lauder’s message loud and clear—the mature and responsible decision for me was to continue the work I was doing as a vocation, a profession, a lifetime occupation. Outreach is not merely something you do in the summer or during a gap year; it is of the greatest possible importance to the future of the Jewish people, and it requires professionalism and a serious commitment. Not everyone is willing or able to do it, but if I am, then it would be an abnegation of responsibility to stop.

JA: Why did you choose to do outreach in Germany?

RS: In 1997, when I needed to make a decision, there were already tens of thousands of Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Germany. I did some research and discovered that there was only one Russian-speaking rav in Germany at the time—for tens of thousands of Jews! Furthermore, there were shuls and communities, but not one makom Torah in the entire country. Now it is understandable why there was no makom Torah in post-Holocaust Germany, but understandable and acceptable are not the same thing. It was unacceptable for a country with tens of thousands of Jews not to have a single beis midrash, kollel or yeshivah.

So I accepted Mr. Lauder’s proposal to work for him doing outreach and chose Germany as my destination, on the condition that I would be able to learn for semichah for a few years while beginning my work part-time. If I was meant to be a credible authority figure in Jewish education, then I had to have appropriate credentials. After that, if I was married and Mr. Lauder still believed in me, I would move to Germany and work full-time.

During the three years I spent learning toward semichah, I spent yamim tovim in small German communities that could not afford rabbis or ba’alei tefillah and spoke with dozens of people to better understand the situation and needs of the Jews in Germany. Everything I learned made it clear to me that this was a place where I could do something important for Klal Yisrael.

JA: Do Jews in Germany have a Jewish identity?

RS: If you are a Jew in America, you can define yourself any way you want—more Jewish, less Jewish, not Jewish at all. This is rarely the case in Germany. In fact, Germany polarizes you. In Germany, you have to ask yourself: How did I get here? I was invited here from Minsk or Moscow or Kiev because I’m Jewish, but is that it? Reparations for the Holocaust—is that my identity? This pushes many Jews, particularly intelligent and proud young people, toward exploring Judaism and identifying strongly with it.

Rabbi Naftali Surovzev, a musmach of Rabbinerseminar zu Berlin, with his kallah Naomi in front of the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin.

JA: How do you view your identity in Germany?

RS: I consider myself a representative of the mainstream Orthodox Jewish world in the US and Canada, and thus the bearer of an enormous obligation. We North American Jews constitute possibly the most affluent Jewish Diaspora community in history. We therefore have an obligation not only to reach out to Jews in our own communities, but to reach out to the entire Jewish world.

When I first arrived in Minsk with YUSSR, locals would ask me, “You’re not Israeli or Lubavitch, so what are you doing here?” I found that to be embarrassing and compelling musar for our community. Why should people be surprised when a representative of the mainstream American Orthodox community is engaged in kiruv? That needs to change.

JA: What is it like raising a frum family in Berlin?

RS: My children attend the day school we established. It is a wonderful place. In fact, when people ask me why I live in Berlin, I answer, “for the chinuch of my children.” This makes people think, as it is the opposite of what they expect to hear. However, chinuch is not only about knowing certain things but about developing values, and I am delighted that my children are being raised with a sense of mission and purpose and pride in being a frum Jew.

One Shabbos several years ago, we attended an aufruf in Antwerp for one of our students. My oldest daughter, who was seven at the time, was blown away when she saw mezuzos on so many doors. The next Friday night back in Berlin, we walked to shul and she said, “There aren’t many mezuzos here. It’s our job to make sure there are more mezuzos in Berlin!” That sense of purpose is chinuch par excellence, and I wouldn’t trade it in for anything.

One Shabbos several years ago, we attended an aufruf in Antwerp for one of our students. My oldest daughter, who was seven at the time, was blown away when she saw mezuzos on so many doors. The next Friday night back in Berlin, we walked to shul and she said, “There aren’t many mezuzos here. It’s our job to make sure there are more mezuzos in Berlin!” That sense of purpose is chinuch par excellence, and I wouldn’t trade it in for anything.

The Fernsehturm, a television tower in the center of Berlin. At 368 meters, it is the highest structure in Germany. Photo: Shutterstock

JA: Why did you decide to reopen Hildesheimers Rabbinical Seminary? Do the communities in Germany need rabbis?

RS: We did not set out to produce professional klei kodesh, but rather bnei Torah. If there was going to be a viable, sustainable future here, it had to be built with ba’alei batim. As the caliber of the ba’alei batim grew, however, so did the need for strong rabbanim. Also, as the yeshivah grew, the possibility of recruiting a handful of truly outstanding young men to serve as spiritual leaders grew too. So we decided to open a semichah track. This semichah track rapidly grew in importance, and it became clear that it deserved and would benefit from becoming an independent institution, rooted in the legendary history of the pre-War training of German rabbis. It has been a huge success. Our musmachim are in high demand, and are now serving as rabbis in Leipzig, Potsdam, Freiburg, Osnabrück and other cities.

JA: How did your father, a Holocaust survivor, react to your decision to live in Germany?

RS: I asked him for his permission. He was fully supportive. In fact, he felt that his experience made him more likely to back me. Do we want to lose more Jews to Germany?

There were, of course, moments of disbelief. My father was born in Czernowitz, a city that at the time of his birth belonged to Romania, but the Jews living there spoke German. So his mother tongue was German. He told me that he never would have believed that he would communicate with his grandchild, my daughter, in German!

JA: What do you envision for the future?

RS: We are so far from where we could be. We run a summer camp for forty kids; we could have 200. We have a yeshivah with forty students and a girls’ seminary with twenty. Both these mosdos could easily double in size with the right resources. We have to open more outreach centers. Freiburg has hundreds of Jewish students in a huge university of 40,000 students. One of our musmachim was recently appointed as the rabbi there and he already has forty students learning. He wants to build a mikvah. One person can’t do everything—be a community rav, do kiruv, build a school, et cetera. He needs a team. We could open more learning programs tomorrow and Jewish students would come. But where is the money going to come from?

JA: To what do you attribute your accomplishments in kiruv?

RS: I could posit many hypotheses. For example, we try to think strategically and use business models, or we are very willing to be moser nefesh, or we work hard to avoid machlokes. But the real reason for whatever success we enjoy is that Hakadosh Baruch Hu deems fit to see us succeed. We humbly pray that that continues to be the case.

Bayla Sheva Brenner is senior writer in the OU Communications and Marketing Department.

To listen to an interview with Rabbi Josh Spinner, visit http://www.ou.org/life/inspiration/what-hitler-couldnt-do-josh-spinner-stephen-savitsky/.