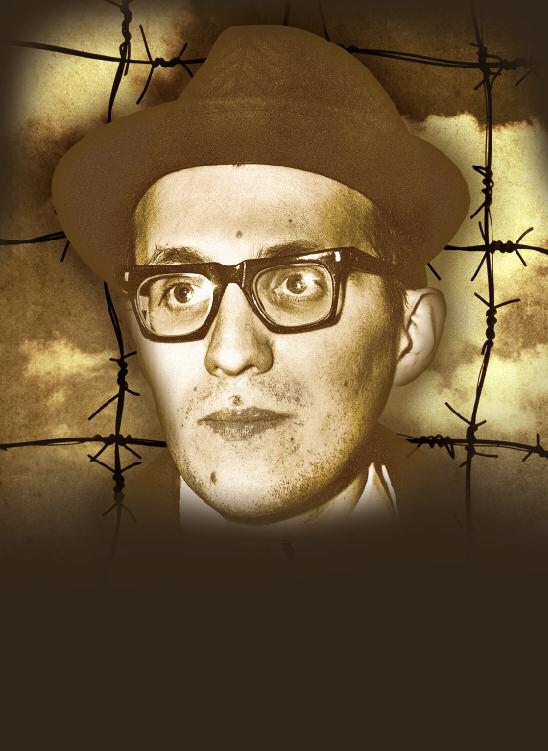

Up Close with Rabbi Yosef Mendelevich

Rabbi Yosef Mendelevich’s tenacious struggle to keep Torah in Communist Russia is documented in his book Unbroken Spirit: A Heroic Story of Faith, Courage and Survival (Gefen Publishing House, Jerusalem, 2012). But in a recent interview with OU Senior Writer Bayla Sheva Brenner, Rabbi Mendelevich, who is today a rebbe at Machon Meir in Jerusalem, reveals more than his story; he reveals the essence of a man who dared to live a Jewish life no matter what the cost.

JA: How did you come to embrace a religious life when living in Communist Russia?

RM: After I dropped out of university, I was called up to enlist in the Russian army. I knew that serving would end my chances of getting an exit visa. I tried coming up with ways to avoid serving in the army. I realized that I was not being honest with myself. I thought, “Yosef, you are struggling to go to Israel, but for what reason? You claim that you would like to go back to your roots, to Avraham, Yitzchak and Yaakov, but they were religious. If you know that it is the truth, why aren’t you keeping mitzvot?” I was forced to make a decision.

JA: How did you start learning about Torah Judaism?

RM: I had a vague understanding of Judaism and picked up scraps of knowledge from different places. There was a duality at home; outwardly, we accepted the Soviet regime, but inwardly we observed some semblance of Jewish tradition. When my mother died, my father married a woman who was more traditional than my mother was. We started keeping Pesach. We didn’t have Haggadahs, so my father would tell us the history of Am Yisrael up until the establishment of the State of Israel. It had an impact on me.

After becoming active in the Jewish underground movement in the 1960s, I was able to get a few sefarim. I read books on Jewish history and a Chumash with a Russian translation. Eventually, I decided to organize a parashat hashavuah study group.

American Jewry saved me; now I hope to save American Jewry.

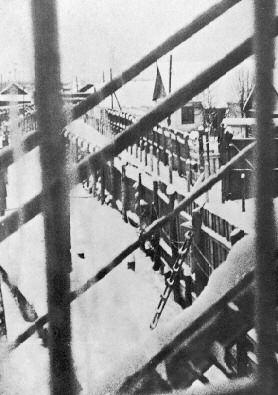

JA: You risked harsh punishment if you overtly behaved as a Jew in prison, yet you persisted. How did you manage to keep wearing a kippah, eating kosher and keeping Shabbos in the Gulag?

RM: To the extent that I was able to keep mitzvot, I did so. I made a kippah out of a pair of pants that was repeatedly confiscated. A friend of mine, who was arrested shortly after me, remembers that when he first arrived at the prison, he saw me lying on the ground as soldiers beat me because I wouldn’t let them remove my kippah.

When the Russians sent me to the “punishment room,” they limited my food rations. I wouldn’t let it bother me; I wouldn’t let them limit my free will. When they gave me my allotted portion, I would deliberately leave some over—making it my decision how much to eat, not theirs.

A few Jewish prisoners and I managed to establish an underground Jewish organization. I was the “rabbi.” We found an unfinished barrack and would gather there on Shabbat. We would lay a white cloth on a table and eat bread that we had saved all week. I would share divrei Torah, which we got from a rabbi in Kibbutz Yavneh in Israel. (Years later, my daughter ended up marrying this rabbi’s grandson.)

JA: How did you manage emotionally without seeing your family for long stretches of time?

RM: My fellow Jewish prisoners were my family. I tried to create a family for myself in each cell I was transferred to. I was always the “father” of the cell. I felt that the other prisoners were my brethren. It is important to have someone to care about—that sustained me.

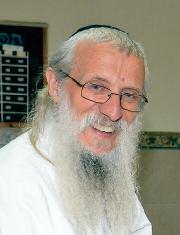

JA: After you arrived in Eretz Yisrael in 1981, how did you end up in yeshivah?

RM: At first, I decided to attend Hebrew University to study international relations. A short while later, I visited a kollel in Glasgow, and the rosh kollel asked me about my plans. I told him I was going to study at Hebrew University and he replied, “But you are a role model for Am Yisrael; you have to study in yeshivah!” When I returned to Israel, a rabbi at Mercaz HaRav said the same thing. Dr. Bernard Lander, the founder of Touro College, called me to relay a message from Rabbi Ovadia Yosef: I have to continue to be a role model for the Jewish people in Israel; I must go learn Torah. But, I thought, I’m not a young man and I’m getting married [I had recently become engaged]; I need a parnassah.

Am Yisrael helped me [sustain myself financially]. Rabbi Moshe Sherer, the former head of Agudath Israel of America, arranged for me to go on a speaking tour. I told my story all over America and was able to make a living from that.

While I was in prison, Rebbetzin Baila Susholz from Brooklyn went door to door collecting donations, hoping to buy my freedom. When I was finally released, she asked a she’eilah about the money she had raised. She was told the funds belonged to me. I used the money for the down payment on our first apartment in Givat Shaul, where my wife and I raised our seven children.

JA: Your spiritual resilience is a powerful lesson for Jews all over. How can we transmit spiritual strength to the younger generation today?

RM: Parents have to be around. That’s the secret—be with your children. The parents’ presence builds the family. If we want our children to follow in our ways, they have to see us and how we live. The father should invite his chavruta into the home to study with him. It’s not enough to send a child to a good yeshivah; you need to set a personal example in the home.

JA: You wrote your book Unbroken Spirit shortly after you came to Eretz Yisrael; why did you decide to translate it into English now?

Rabbi Yosef Mendelevich with the tzitzit he made while in prison. Photos courtesy of Gefen Publishing House

RM: When I first came to Israel, my brother-in-law, who was also a member of our underground movement in Russia, urged me to write my story, which I did. A few years ago, a group of American Jews who were formerly involved in the movement to free Soviet Jewry suggested I have the book translated into English. I decided to do so in order to educate and inspire American Jewry. American Jewry saved me; now I hope to save American Jewry.

Since outside of Israel New York is the largest Jewish city in the world, I asked my friend Glen Richter, the co-founder of the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, to organize speaking engagements for me there. He found it very difficult—almost no one was interested. People think I’m still telling the story of Soviet Jewry. My story is not about Soviet Jewry; it’s about emunah and the strength of the Jewish neshamah.

JA: What has been the reaction to the book?

RM: Some individuals have written to me saying that the book has changed their lives. One American woman said that she was hesitant about becoming more involved in Judaism, but after she read my book, the decision to do so became clear. This is exactly what I had hoped for—to instill bitachon and emunah in people.

RM: Some individuals have written to me saying that the book has changed their lives. One American woman said that she was hesitant about becoming more involved in Judaism, but after she read my book, the decision to do so became clear. This is exactly what I had hoped for—to instill bitachon and emunah in people.

I’ve been a popular lecturer for over thirty years now. I’ve repeated my story again and again and sometimes I ask myself, was it real? It is a miracle for me. Every time I speak to an audience, I get a kind of ruach hakodesh and I tell my story emphasizing exactly what each particular audience needs to hear.

JA: As a Jew who believes in hashgachah pratit, why do you think Hashem deemed that Yosef Mendelevich be born in Communist Russia and find a way to blossom as a Jew in that environment?

RM: I’ve thought about that. I have no explanation, but I am thankful to the Ribbono Shel Olam for having selected me for this mission. It is the reason I wrote my book, to show how, with the help of Hashem, it is possible for even an assimilated Jewish boy living in Soviet Russia to find his Jewish neshamah. It is my hope that the next generation of Jews will read the book and think, “If a simple Jew like Yosef Mendelevich could do it, I can too.”

Bayla Sheva Brenner is senior writer in the OU Communications and Marketing Department.