The Revival of Jewish Life in Poland

Warsaw

Warsaw

Photo: Ahron D. Weiner/www.ahronphoto.com

The big news in Krakow’s Jewish community last year didn’t make the news.

A young Jewish couple got married. The bride and groom, typical of Polish Jews in their twenties, had been raised without a Jewish education; they eventually discovered their Jewish identities, learned about Judaism and decided they wanted to lead observant lives. Their closest friends came to the wedding, a modest affair, with Rabbi Michael Schudrich, the country’s chief rabbi, serving as mesader kiddushin.

The wedding did not make headlines, inside or outside of Poland. Ten or twenty years ago, an Orthodox wedding of two Polish Jews in Poland would have been remarkable.

Today, two decades after the Solidarity movement in Gdansk set in motion the stirrings of freedom that brought down Communism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Jewish lifecycle events conducted according to Jewish tradition are “far more normal than they were five years ago,” says Rabbi Schudrich.

A native of Long Island who has worked in Poland since 1990, first as the representative of the Ronald S.Lauder Foundation, now as chief rabbi, Rabbi Schudrich has seen the growth of Jewish life here and the emergence of a small but dedicated Orthodox community. Which, by definition in a country where the practice of Judaism was once punishable under atheistic Communism, means a ba’al teshuvah movement.

Anyone who keeps any mitzvot in contemporary Poland is automatically a ba’al teshuvah, a former tinok shenishbah,and, ironically, often a convert– many young Jews who find out that they have “Jewish roots” also find out that they may not be halachically Jewish. If they desire to lead full Jewishlives, they choose to undergo a completeor symbolic geirut (that is, immersion in a mikvah, a pledge to lead an observant lifestyle, and for men, a brit milah as well).

On the eve of 5771, the number of Polish Jews who are “full-fledged”frum ba’alei teshuvah according to Western ba’al teshuvah standards probably totals a couple dozen families, Rabbi Schudrich says. But, he says, there are many more who “are keeping more mitzvot than they did a few months ago. The Yiddishe neshamah doesn’t go away.”

More Polish Jews are going to synagogue, keeping Shabbat and kashrut, putting mezuzot on their doors, and using the country’s few mikvaot.

How many Polish Jews were davening, eating kosher or keeping Shabbat when Rabbi Schudrich first arrived in Poland? “Zero, zero and zero,” he says.

The rabbi has documented the phenomenon of unknown Jews, from Communist or Catholic backgrounds, coming out of the woodwork, the older ones comfortable identifying themselves when the danger had passed, the younger ones investigating Judaism when their true background is revealed upon parents’ and grandparents’ deathbed confessions. It’s still happening, though not as frequently as in the immediate post-Communist days.

Sometimes, subtle clues cause Poles to suspect Jewish blood in their family. Silence when Jewish topics are raised. Unexplained friends or relatives in Israel. Whispering at school.

“I knew I had Jewish roots. It wasn’t important,” says Michal Samet, from Gdansk, who learned officially that he is a Jew sixteen years ago. He visited Israel, felt at home in places like Bnei Brak and Meah Shearim and studied at a yeshivah. Today, he leads his hometown’s small Jewish community.

“I always suspected–” says Maciej Pawlak, from Szczecin, who, when his suspicions were confirmed, decided to study at Yeshiva University. The first Polish-born rabbi since the Shoah, Rabbi Pawlak is principal of the Lauder-Morasha School, a Jewish day school in Warsaw founded by the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation.

Sometimes, when Poles find out they are Jews, they have little or no warning.

“It was a shock,” says Pawel Bramson, from Warsaw. Bramson’s wife turned up documents that showed both of them were Jewish. Bramson may be Poland’s most-celebrated ba’al teshuvah. He was an anti-Semitic skinhead. Today, with a beard and black hat, he works as a mashgiach and shochet. “I’m doing teshuvah all the time,” he says.

Likewise, says Marcin Dudek- Lewin, from a town in northern Poland. His grandmother told him, at ten, that he is Jewish. He moved to Warsaw, studied with Rabbi Schudrich, and decided to become shomer mitzvot. “My soul spoke to me,” he says.

“I didn’t even know there was a synagogue in Poland,” says Beate Shulman, from Krakow, whose mother remarked in passing that their family is Jewish. Her subsequent study of Chassidism intrigued her. She became active in the Jewish community, and then became a ba’alat teshuvah.

Krakow Ghetto

Krakow Ghetto

Photo: Ahron D. Weiner/www.ahronphoto.com

As elsewhere, Poland’s ba’alei teshuvah tend to adopt a religious lifestyle in their twenties and thirties, the time of self-identity choices.

As elsewhere, they range in style and affiliation, from Modern Orthodox to Chassidic, some simply calling themselves “observant.”

These ba’alei teshuvah are rebuilding a Jewish community. They are restoring a lost legacy. “They want to be like their grandparents or great-grandparents,” who were or presumably were Orthodox, Rabbi Schudrich says.

These ba’alei teshuvah are rebuilding a Jewish community. They are restoring a lost legacy. “They want to be like their grandparents or great-grandparents,” who were or presumably were Orthodox, Rabbi Schudrich says. They are visible signs of a revival that has turned into a community. This in a country whose affiliated Jewish population is about 5,000, and whose total community of people who don’t know they are Jewish or are still afraid to admit it is estimated between 10,000 and 20,000.

The nascent ba’al teshuvh movement here is smaller than in other ex- Communist lands in the region like Hungary (Jewish population: more than 100,000) and the former East Germany (now-unified Germany has more than 100,000 Jews, mostly from the former Soviet Union).

Every ex-Communist country has some men and women returning to Torah-true Judaism. “There’s a trend, you can see it in Israel as well, that Eastern European Jews, if they return to their roots, they do it all the way and very thoroughly,” Olaf Gloeckner from the Moses Mendelssohn Center for European- Jewish Studies in Potsdam, Germany, told the Jerusalem Post.

For individuals whose Communist identity and ethos were stripped away, a religion with many rules is reassuring, Bramson says.

But Poland is special. Because the country is the home of the world’s largest pre-Holocaust population, any signs of Jewish life in Poland are symbolic to the broader Jewish community.

Poland is different from the other one-time-Communist societies. Religion never died here. The Catholic Church, which produced a pope, John Paul II, who established closer relations with the Jewish community, remained influential in Poland during Communism.

Children singing Jewish songs at the Lauder-Morasha School in Warsaw. The Jewish day school was established in 1994 by the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation. Courtesy of Lauder-Morasha School

Children singing Jewish songs at the Lauder-Morasha School in Warsaw. The Jewish day school was established in 1994 by the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation. Courtesy of Lauder-Morasha School

Today’s Poles, says Rabbi Schudrich, respect religion–even another person’s religion. “Poland is still a very religious country, very church-going, a God-centered society.”

Modern Polish Jews are heirs toHitler’s martyrs. However, today’s Polish ba’al teshuvah movement was not a given.

Konstanty Gebert, a prominent labor activist-turned-journalist who led the Flying Jewish University when open Jewish education was banned, says a fellow Jewish Solidarity member asked him in 1980, “How do you see the future?” Would Jewish life continue in Poland?

“I believe we are the last ones. Definitely,” Gebert answered.

“And there will be no Jews in Poland?”

“In the sense of a religious, national group, no,” Gebert said. Gebert is no prophet.

Now he calls himself a religious Jew. He is shomer Shabbat. He and his wife have a kosher home. He wears a kippa all the time.

When he embraced observant Judaism, “I was the youngest congregant by two generations.”

Now, at fifty-seven, surrounded in shul in Warsaw by a younger generation of Orthodox Jews, “I am counted among the ‘older generation,’” he says.

Gebert, who because of his eloquence and openness has become a de facto spokesman for Polish Jewry, has a typical story.

Pawel Bramson, one of Poland’s most celebrated ba’alei teshuvah, is a former skinhead. Photo: Lach/IHT/Redux

Pawel Bramson, one of Poland’s most celebrated ba’alei teshuvah, is a former skinhead. Photo: Lach/IHT/Redux

“I had absolutely no Jewish upbringing,” he says. “My parents were pre-War Communists. Jews were not discussed at home for the same reason Eskimos weren’t–irrelevance. We were so assimilated that we didn’t even deny we’re Jewish; it was that unimportant.”

Then, in the first blush of freedom, he started to read about Judaism. “The turning point came when I read the midrash on matan Torah,” the Jewish belief that all Jewish souls stood at Mount Sinai and accepted the Torah for the ages, Gebert says. He was impressed that “the children will be the guarantors for Hashem.”

“I realized,” he says, “that I am one of those guarantors–and this means that I would need a good reason to justify my not living an observant life. So we decided, my wife and I, to introduce as much observance into our lives as physically possible–almost as a social science experiment. This was Warsaw in 1980. We had two small children, very little money and life was hard already. Adding observance practically turned it at first into a nightmare. But we stuck to our guns, adapted and compromised–and, one year later, decided we want to keep living that way, for it had given our lives new depth and meaning.”

Gebert, a columnist and foreign correspondent for the prominent Gazeta Wyborcza newspaper and founder of the Midrasz monthly magazine, is the author of several books. His 54 Commentaries to the Torah, issued in 2004 in Polish and the following year in English by a Krakow publisher, took its place among a growing number of books in Polish–originals, like his; and translations from English and Hebrew–about traditional Judaism. In a country with few Jews, such books reach a wider audience.

More Polish Jews are going to synagogue, keeping Shabbat and kashrut, putting mezuzot on their doors, and using the country’s few mikvaot.

“This reflects the relatively recent but abiding interest of Poles in things Jewish,” he writes in the introduction to his Torah commentary.

After 54 Commentaries came out, Gebert writes, he realized “that this was the first such book published in the Polish language. Torah commentaries had been popular in Poland over the ages. But they were always written in Hebrew or sometimes Yiddish . . . The idea of publishing such a book in Polish alone, or even of translating an existing book into Polish, would strike people before the Shoah as fanciful, if not plain absurd. Interested readers who could read only Polish simply did not exist.”

Came the Holocaust, which “destroyed the readers and burned their books.”

Then came a Jewish renaissance in Poland.

Then came Gebert’s commentary, which he wrote for his generation of minimally Jewishly literate young Jews.

The uniqueness of his book did not last long, “barely a couple of months,” Gebert writes in his book. “Soon Stanislaw Krajewski, an intellectual and spiritual leader of our community, published his [Torah commentary] – and Pawel Spiewak, a renowned political scientist earlier not active in Jewish communal life, followed hot on his heels with his Midrashim.”

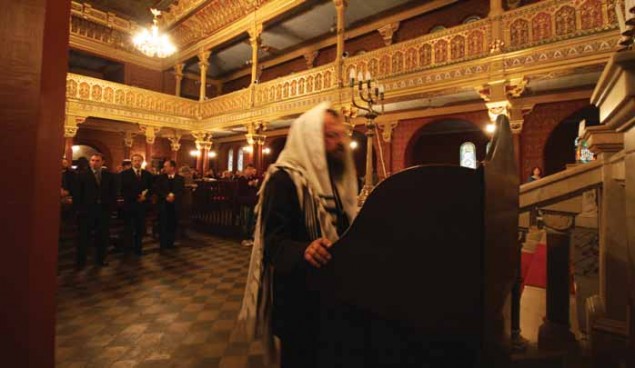

The Krakow Synagogue

The Krakow Synagogue

Photo: Julian Voloj/Courtesy of JDC

With the support of the American based Lauder Foundation, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), the Taube Foundation for Jewish Life and Culture, and Israel’s Shavei Israel, along with chinuch provided by Rabbi Schudrich and a growing cadre of Orthodox rabbis in Poland, many of them Chabad shluchim, Polish Jews are discovering what it means to be Jewish.

Despite the distressingly frequent comments of visiting Western Jews that Jewish life in post-Holocaust Poland is neither possible nor desirable, Polish Jews say they can lead a fully Jewish life here. Orthodox families invite each other for Shabbat meals. In Krakow, a university town, scores of single Jewish students have shaped their version of New York’s Upper West Side, celebrating Judaism among themselves. Employees can take off for Shabbat and Jewish holidays. There are day schools for the children, and adult education classes for the parents. Kosher wine is available in liquor stores, kosher food with a hechsher in supermarkets.

“There are more and more kosher products being sold in Poland, both under my hashgachah and [with hashgachot] from abroad,” Rabbi Schudrich says. “We are now publishing a new kosher list with thirty-five pages of items.”

“We are,” Gebert writes in Living in the Land of Ashes, his 2008 intellectual biography, “in the process of becoming, numbers allowing, just another small, boring Jewish community.”

What is Poland’s Jewish future? Will Orthodox life continue here?

“It is by no means certain,” Gebert writes, “that the enthusiasm of the new ‘young Jews’ will suffice to create the critical mass needed for survival.”

But the signs are good.

“There is a possibility,” Rabbi Pawlak, the principal of the day school, says. “Poland is not a Third World country. Sometimes we don’t appreciate what we have here.”

Many young couples, especially those with children, are staying in Poland, he says. Like the young couple who got married in Krakow last year. They moved to Warsaw and are working for the Jewish community.

The biggest problem sounds familiar: young ba’alei teshuvah move away, for shidduchim or for their own or their children’s education.

“There is a feeling that we cannot build our houses on sand,” Bramson says. “It’s hard to build a community based on ba’alei teshuvah when we don’t have really strong [educational] foundations. Everyone is in a learning process.” There aren’t enough rabbis here, he says. Bramson says his family may leave Poland for the children’s sake.

Beate Shulman now lives in Queens, working for two Polish based Jewish organizations, building a social life with other now-Orthodox Polish Jews in the New York area. When she lived in Krakow, she was part of a small chevrah of newly Orthodox Jews. “Most of them are in Israel now,” she says.

But other young Polish Jews are joining the ranks of the departed ba’alei teshuvah. New faces show up at synagogue. Strangers still come to Rabbi Schudrich when they discover they are Jewish. Gebert has left the editorship of Midrasz, replaced by younger writers.

“I always told people, Poland will arrive as a Jewish community when we don’t have any more ‘firsts,’” Rabbi Schudrich says. “The first ‘this,’ the first ‘that.’” Wedding, brit milah, Bar Mitzvah, et cetera.

“We’re there,” the rabbi says. “At this point we’re not doing any [more] ‘firsts.”

He officiated at a Bar Mitzvah earlier this year. Only relatives and friends came. No reporters. “It’s not news.”

Steve Lipman is a staff writer for the Jewish Week in New York.