Out of Africa

Close to 8,000 Falash Mura-descendants of Ethiopian Jews who converted due to missionary work and persecution–live in the Gondar region of Ethiopia. The Israeli government plans to bring them all to Israel within the next four years. Photos from Atalia Katz’s photographic exhibition “Voice of Ethiopia,” which captures the day-to-day life of Ethiopian Jews.

Close to 8,000 Falash Mura-descendants of Ethiopian Jews who converted due to missionary work and persecution–live in the Gondar region of Ethiopia. The Israeli government plans to bring them all to Israel within the next four years. Photos from Atalia Katz’s photographic exhibition “Voice of Ethiopia,” which captures the day-to-day life of Ethiopian Jews.

The little-known but fascinating Jewish communities of East Africa sprung to life in the late nineteenth century, thrived for over half a century and are now nearly extinct. Recently, Ari Z. Zivotofsky and Ari Greenspan embarked on a trip to some of these war-torn, impoverished countries to discover more about these communities. Here is their report.

When one thinks of countries like Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Djibouti, African tribes, civil wars and famines come to mind. Certainly one does not think of Jewish communities. Yet, traditional Jewish communities existed in all of these African countries.

Ethiopia

Although Ethiopia is one of the poorest countries in the world, it is spectacularly beautiful. Parts of it are lush and green, other parts are desert. It has extinct volcanic lakes, rivers and high mountains. Ethiopians are warm and friendly. Amharic, the predominant language of the country, has a soft ring to it, and because it is Semitic in origin, it can sometimes sound like Hebrew.

When one hears of Jews in Ethiopia, one thinks of the Beta Yisrael (House of Israel), the black Jews. According to some scholars, the Beta Yisrael have lived in the country since the time of King Solomon, close to 3,000 years ago. Clearly, the Beta Yisrael view themselves as Jews. The Radbaz (Rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Zimra), the leading posek in Egypt in the sixteenth century, thought the Beta Yisrael are the descendents of the Tribe of Dan. In 1973, partly based on that ruling, the then chief rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Ovadiah Yosef, ruled that they are halachically Jews. This paved the way for Operation Moses in 1984 and Operation Solomon in 1991, when the Israeli government airlifted thousands of Ethiopian Jews, rescuing them from political and economic distress, and brought them to Israel. Today, more than 100,000 Ethiopian Jews live in Israel.

In Gondar, minyanim with hundreds of worshippers take place three times daily.

In Gondar, minyanim with hundreds of worshippers take place three times daily.

Over the last 200 years, persecution and Christian missionary work caused some among the Beta Yisrael community to convert to Christianity; the Falash Mura are the descendants of these converted Jews. Many of the Falash Mura claim that they continued to keep their Jewish rituals in secret, similar to Conversos. Some 8,000 Falash Mura still live in and around Gondar.

Recently, the Israeli government decided that the Falash Mura will be allowed to immigrate to Israel over the next four years. Once in Israel, they will have to undergo a strict conversion to Judaism, overseen by the Chief Rabbinate.

When one thinks of countries like Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Djibouti, African tribes, civil wars and famines come to mind. Not Jews.

What we saw on our recent trip to the Gondar region of Ethiopia astounded us. With the help of the North American Conference on Ethiopian Jewry (NACOEJ), the Falash Mura are living a halachic lifestyle. The community boasts an impressive school offering both Jewish and secular studies, a food program that provides meals for thousands, Jewish education classes, and a mikvah. Minyanim with hundreds of worshippers take place three times a day, and the women’s mikvah is in constant use. Unfortunately, there is a missionary center nearby masquerading as a synagogue.

Adenites in Addis Ababa

The purpose of our trip to Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, was to visit the non-native Ethiopian Jews, or members of the Adenite Jewish community. These Jews’ ancestors came to Ethiopia from the port city of Aden in southern Yemen. Jews have lived in Aden for thousands of years. Some maintain that the boats of King Solomon landed there, and that the Jews who lived in Aden were descendants of those sailors.

In 1839, Aden was captured by Great Britain, who turned the small village of 600 including 250 Yemenite Jews, into a major trading hub and port. The Jewish community of Aden was ancient: in 1866, Rabbi Yaakov Sapir of Yerushalayim visited Aden on his tour of Jewish communities of the East. He described 2,000-year-old Jewish graves uncovered when the British began building army barracks. Evidence gleaned from the Cairo Geniza also tells of a thriving Jewish kehillah that existed in Aden in the High Middle Ages. Shortly after the British conquest, Jews from Iraq, Iran, India and the Turkish Empire found themselves in Aden in order to conduct business. The Jews in British Aden, unlike those in other parts of Yemen, were granted full rights, enabling them to succeed financially and otherwise. And succeed they did. The community reached its peak in 1947; out of a total civilian population of 78,400, more than 8,500 were Jewish. The British also exposed the population to Western culture and ideas. Schools for boys and girls were opened. Western attire was adopted. All of this was unprecedented for Jews in the Arabian Peninsula.

In the late 1800s, much opportunity awaited those who crossed the narrowest point of the Red Sea into Africa. A number of Adenite businessmen traveled to Africa to try their luck. The wealthy Adenite Banin family soon became involved in trading and found opportunities in places like Dire Dawa, Ethiopia and Asmara, Eritrea. In the African port of Djibouti, a lawless, wild, boiling hot and humid Muslim country bordered by Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia, a shul was built and a Jewish community formed. As these communities developed, Jews built houses and opened shops. Often times, shochetim, teachers and ba’alei keriah–from the more knowledgeable Yemenites–were brought over from “the Old Country” to assist the kehillot in East Africa. Most of the countries in East Africa bear the mark of the Banin family.

The Shul in Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa, considered one of the more developed cites in Africa, is rife with poverty, open sewers and failing infrastructure. More than one hundred years old, the Jewish community in Addis Ababa, a city of more than three million people, reached its peak in the 1960s when some 500 Adenites from South Yemen and several hundred Israelis lived there. In the early 1970s, following the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassei by the brutal communist Mengistu and the beginning of numerous civil wars in Ethiopia, the Israelis were forced out, and many of the Adenite Jews fled. Within the last decade, however, things have improved greatly. The civil strife has ended, and relations with Israel have normalized. The Adenites who retained businesses in Addis Ababa, even those who moved their families to Israel or Europe during the period of unrest in the country, are currently spending more time in Addis Ababa.

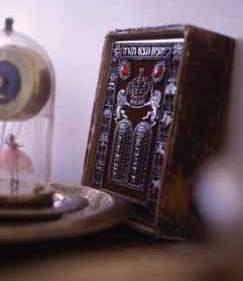

The one-hundred-year-old shul in the city, called Succat Rahamim, is a single room, about twenty feet on each side. Decades ago, from the 1950s until the early 1970s, the shul was a center of activity. Today, the shul has had neither a rabbi nor a steady minyan. Located on the second floor of a nondescript building, the shul has unusually thick walls with deep recesses in which sefarim are held. The unusual architecture tells a story: the structure was not originally built as a synagogue. In fact, the sanctuary used to be Banin’s cash room. Since there were no banks in those days, he used to store silver and gold within the deep crevices in the wall.

Label of Kosher meat, produced in Israel for exports to Asmara.

Label of Kosher meat, produced in Israel for exports to Asmara.

Interestingly, the shul is located on a street called Beni Sefer. Locals informed us that the street sign should really read “Banin Sfar,” or “Banin’s area.” Banin was not satisfied with the construction workers he found in Ethiopia, and so he brought over Muslim Yemenites to construct his home and the shul. He erected a small mosque for them across the street from the Jewish area. Today, Muslims constitute a significant percentage of the population, and the old mosque is no longer big enough for their needs. Recently, a Saudi prince donated funds to construct a new central mosque in Addis Ababa. In place of the old mosque, a massive structure is being erected, which, because of the location, will be called Banin’s mosque. Amazingly, the enormous main mosque of Ethiopia will be named after a pious Jew!

Ari Z. Zivotofsky and Ari Greenspan in a market in Djibouti. Courtesy of Ari Zivotofsky.

Ari Z. Zivotofsky and Ari Greenspan in a market in Djibouti. Courtesy of Ari Zivotofsky.

We first visited Addis Ababa back in 1987 when we participated in a NACOEJ mission. We spent Shabbat with the community (and brought with our own shechitah knives in order to provide the small community with kosher chicken for Shabbat). We also explored the shul’s genizah, a treasure trove of old sefarim, some as old as 300 years. Unfortunately, during this recent visit, we discovered that time had turned much of the old precious books in the genizah to dust. The holy books that generations of Adenites had worshipped from and studied with are now totally worthless.

Time has turned much of the old precious books in the genizah in Addis Ababa to dust. Courtesy of Ari Zivotofsky

Time has turned much of the old precious books in the genizah in Addis Ababa to dust. Courtesy of Ari Zivotofsky

Currently, between twenty-five to fifty Jews live in Addis Ababa; the number of Israelis living there full or part time is growing. Thankfully, there is a feeling of camaraderie and friendship within the small Jewish community. Unfortunately, however, facilities for the community are sorely lacking. The only public mikvah in Addis was destroyed years ago (there is one in a private house). The few Jewish children attend international schools, and kosher food is hard to come by. Nevertheless, as unlikely as it may seem, the Jewish community of Addis Ababa is actually growing.

Eritrea

Adenite Jews came to Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, seeking new commercial opportunities in the late nineteenth century. They were later joined in the 1930s by a smaller number of Ashkenazim fleeing anti-Semitism in Europe. Asmara is a charming city towering 8,000 feet above Eritrea’s sultry lowlands and blessed with almost perpetual sunshine and cool breezes.

The synagogue in Asmara, now empty, testifies to the once rich Jewish life that existed in this quaint former Italian colony. Photos by Marco Mensa (ethnosfilm.com), unless indicated otherwise.

The synagogue in Asmara, now empty, testifies to the once rich Jewish life that existed in this quaint former Italian colony. Photos by Marco Mensa (ethnosfilm.com), unless indicated otherwise.

The Jewish community of this quaint former Italian colony peaked in the 1950s when about 500 Jews lived there. But Jews began leaving when Israel gained independence, and most departed when the violence of Eritrea’s thirty-year struggle for independence from Ethiopia came to Asmara in the mid-1970s.

Back in 1987, we had wanted to visit Asmara but were unable to because the war was raging, and there were safety concerns. Currently, the situation is stable—the war ended in 1991—nevertheless, one still cannot travel directly between the two countries.

Facade of the synagogue in Asmara

Facade of the synagogue in Asmara

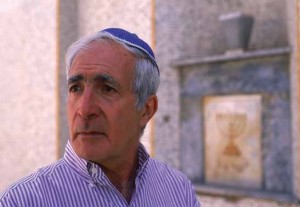

While the Jewish infrastructure in Asmara is in better shape than it is in Addis Ababa, the Jewish community itself is in much worse condition. A short walk around the town reveals the Jewish ghosts in the city. A large house built by the Banin family and owned by Shoa Menachem Joseph, president of the community from 1916 until 1965, is today a hotel, known as Pension Milano. Artistically designed Magen Davids are carved into the ceilings and on the stained-glass windows. In many of the doorways, dark marks where mezuzot once hung are evident. Who could not help but feel the spirit of days past? The last Jew in Asmara is Sami Cohen, whose family originally hails from Aden. Cohen’s grandparents moved to the Eritrean port of Massawa at the turn of the twentieth century. (We did not visit Massawa because Eritrean regulations, much like the old Soviet Union, require a permit to leave the capital.)

Cohen, who is in his sixties, remembers the glory days of the community when the school was active, and lively discussions rang from Jewish stores in Asmara. Cohen’s wife and daughter left Eritrea when the country went to war with Ethiopia in 1998. Nevertheless, Cohen dutifully looks after the shul, hoping for the day there might be a revival. The shul, which can seat between 150 and 200 men in the main sanctuary, is locked throughout the day. It is evident, however, that it was well used at one point.

The aron kodesh holds two sifrei Torah, and well-worn siddurim line the shelves. Cohen remembers the Jewish classroom off the courtyard of the shul where today he keeps old sefarim and community papers. The mikvah is no longer functional and is located in the synagogue courtyard. At one point, the community was comfortable enough to support others. The Jews in Asmara would send money back to the “Old Country”! Similar to North African shuls, the shul in Asmara has tzedakah boxes built into the side of the bimah, including one box labeled “the poor of Aden.” Five years ago, the shul in Asmara celebrated its centennial, for which many Jews returned to the city.

Evidence of a vibrant Jewish community, now forgotten.

Evidence of a vibrant Jewish community, now forgotten.

Djibouti

During our visit to Addis Ababa, we heard that Adenite communities had also existed in Kenya, Somalia, and Djibouti (we were not prepared to visit the first two). We arranged to fly from Ethiopia to Djibouti for a day, after frantically arranging for visas.

Arriving in Djibouti, a tiny country sandwiched between Ethiopia and Somalia, one is first struck by the 120-degree heat, then by the male taxi drivers in African skirts. Steering wheels in the taxis are randomly placed on either the right or left in this poverty-ridden Muslim county.

We had only sketchy directions, having been given the name of a hotel in which the air conditioning worked. Once we reached the hotel, we struck up a conversation with the owner who eventually became our “tour guide.” Most amazingly, he was the last president of Djibouti before it achieved independence from France—and he had once even been a Shabbos goy! He showed us where the shul building had stood when he was growing up and fondly recalled playing there as a child every afternoon with his friend Mordechai, who apparently went on to become a general in the Israeli Army.

Sami Cohen, the last Jew in Asmara.

Sami Cohen, the last Jew in Asmara.

The Jewish community in Djibouti had never been large, numbering just a few hundred. It existed for about half a century, disbanding in 1948, just after the founding of the State of Israel. Like the Addis Ababa and Asmara communities, the community in Djibouti was founded by Adenite businessmen looking to expand their trade. Djibouti is a major port on the Red Sea and naturally attracted Adenite Jewish businessmen.

One of our acquaintances, Shalom Sion, who lives in London and travels to Addis Ababa frequently for business, has a personal connection to the extinct Jewish community of Djibouti. Sion’s maternal grandfather served as the last chief rabbi of the community.

The small Jewish cemetery in Asmara

The small Jewish cemetery in Asmara

A community building with a large Magen David evident on its crumbling facade is one of the few visible remnants of the former kehillah. The small Jewish cemetery, fenced off within the Christian cemetery in this predominantly Muslim country, seems to be cared for.

The poverty in the city of Djibouti, the only city in this small country, is astounding. While walking around the cemetery fence to find a way in, we came across a tiny hut consisting of a tin roof and tattered plastic sheets flapping in the wind. This makeshift tent, sitting on a hot spit of sand, was home to a family with three children in ragged clothes.

It is difficult to imagine that a Jewish community once existed here. The few Jews who still reside in Djibouti conceal their religion. In Djibouti, we met two great-grandsons of Adenite Jews who had lived in Asmara. They are first cousins, and both intermarried. They asked that we not use their names as they live in a Muslim country. One of them had memories of his grandfather keeping Shabbat.

What happened to the community in Djibouti? How come there is no Jewish community in Djibouti today? The Jews were neither expelled nor fled from persecution. The several-hundred-strong Adenite community had been raised on the Yemenite tradition of longing for the Land of Israel, and in 1948, when moving to Eretz Yisrael became a real option, the community made aliyah en masse.

Additionally, during Operation Magic Carpet, the Israeli government, in addition to airlifting the Yemenite community, also brought the small Jewish communities of Aden, Djibouti and Asmara to Israel. In fact, Sion Moshe, a ninety-year-old member of the Adenite community who spent his formative years in Djibouti–and currently lives in Holon, Israel–told us he recalled the day “a plane came from Aden and we all got on and flew to Israel.” Prior to moving to Israel, his father had served as the rabbi, chazzan, shochet and sofer of the Djibouti community.

Subsequent to the creation of Israel, the Adenites created a strong, vibrant community in the Holy Land. There are today Adenite shuls in a dozen Israel cities and a central organization (www.adencommunity.org) devoted to preserving their unique minhagim and passing them on to their children.

Rabbi Dr. Zivotofsky, a Jewish Action columnist, is on the faculty of the Brain Science Program at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. Dr. Greenspan is a US-trained dentist with a practice in Israel.

Rabbi Dr. Zivotofsky and Dr. Greenspan have spent over twenty years together collecting Jewish traditions from far-flung Jewish communities. More information on their research can be found at http://halachicadventures.com.

The editors extend a special thanks to Sami Cohen from Eritrea for helping to prepare this article.