Why Data Matters: A Conversation with Social Scientist Matt Williams

Jewish Action recently spoke with Matt Williams, director of the OU’s research arm, the Center for Communal Research, which collects and analyzes data from the Jewish community.

Jewish Action recently spoke with Matt Williams, director of the OU’s research arm, the Center for Communal Research, which collects and analyzes data from the Jewish community.

Matt joined the OU after serving as the managing director of the Berman Jewish Policy Archive. He holds degrees in art history, English and Jewish studies from Yeshiva University, received a master’s degree in history and public policy, and is currently finishing a doctorate degree in education and history with a concentration in Jewish studies from Stanford University. He and his wife Amy and son Emmett live in Irvine, California.

Jewish Action: With a background in art history, what made you move into the field of social sciences, and what do you like about this field?

Matt Williams: In many ways, I struggle with the label of social scientist. It’s something that I do, but I really think of myself as a researcher who is more interested in questions. I’ve always been driven to ask questions: How does one learn how to be Jewish? How does that express itself within and alongside institutional Jewish life? And how do we, Jewish communal professionals, help or hinder that process?

JA: As director of the Center for Communal Research at the OU, can you explain the role and goals of the Center?

MW: Firstly, the Center aims to study the Orthodox community and provide the necessary data to better identify the challenges we face; opportunities we can take advantage of; and priorities in creating and implementing solutions.

Secondly, in addition to understanding what our problems are, we need to better understand what works and what doesn’t. What are the best approaches to fostering a commitment to observance, a relationship with Hashem? What are the best ways to reduce poverty or address other economic issues facing our community?

Thirdly, in addition to conducting general communal research, the Center is responsible for evaluating OU initiatives in particular. We want to better understand the programs that we’ve put out into the field and to assess their effectiveness. We want to be able to determine the impact of an NCSY program or an Israel Free Spirit Birthright Israel program by delving into the lives of the participants as well as the educators, and studying the structure of the program, its materials and the pedagogies employed.

JA: For thousands of years, Jewish communities did not engage in any kind of self-study. Why is it necessary now to research Orthodox Jewish life and collect data?

MW: The Orthodox community—every community in fact—has always engaged in self-study. We love talking about ourselves. If we’re going to talk about ourselves constantly anyway (at the Shabbat table, for example), and if those perceptions and opinions are going to affect our communal practices and policies, then wouldn’t it be sensible to conduct a cheshbon hanefesh in a rigorous way? Responsible communal leaders should use research to impact policy decisions on everything, from what’s the best way to run a Shabbaton to how organizations should allocate millions of dollars each year. One of the ways that we as a community waste funds is by investing resources in programs when we have no idea, beyond anecdotal evidence and customer satisfaction surveys, if they work or not, and then not learning if they do.

JA: The secular American Jewish world has been engaged in researching the Jewish community for decades. Why has the Orthodox community lagged behind?

MW: The secular Jewish establishment has engaged in research since the early 1970s. Hayim Herring [the well-known organizational futurist] wrote a famous article on the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey [“How the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey Was Used by Federation Professionals for Jewish Continuity Purposes,” 2000], in which he questions how the study was received by Jewish communal professionals. He found that the vast majority had heard of the study and could parrot its major findings but had never actually read the study. So the extent to which research is used to inform policy and decision-making even in the non-Orthodox community is an open question. One of the things I’ve been most impressed about at the OU is the seriousness with which our lay and professional leadership takes data into the decision-making process. And I say this after having worked not only in the non-Orthodox world but in the non-Jewish nonprofit sector as well.

One of the ways that we as a community waste funds is by investing resources in programs when we have no idea, beyond anecdotal evidence and customer satisfaction surveys, if they work or not.

The fact is that the Orthodox community in the United States was small up until fairly recently. That has changed in the last several decades. The natural consequences of the high birth rate and rapid growth of the community are disconnection, diversification and variation. When a community of 500 families becomes 5,000 families, there’s a significant change in the culture; people grow apart.

The more we lose that personal knowledge and understanding of the communities in which Jews live, the more we have to approach the learning as a process.

The non-Orthodox American Jewish community was always a large community of unaffiliated Jews, so it needed to have those tools at its disposal for a long time. For the Orthodox community, being a large community is a relatively new phenomenon.

JA: Interesting. How new would you say research and data collection are to the Orthodox community?

MW: Social science research only began to enter the Orthodox Jewish communal vernacular in a serious way at the beginning of the twenty-first century. A few major outreach organizations, such as Olami, Afikim Foundation and Ner LeElef, were very interested in obtaining data, which began to influence the ways our community approached kiruv in particular. Through these organizations, among a few others, research slowly filtered into the Orthodox establishment (to the extent that we could talk about an establishment in the Orthodox community in the same way we do in the non-Orthodox community). I believe there’s a growing recognition that we need data to inform our decisions; that we don’t fully understand our community in the ways we assume we do; and that there are areas in which we can improve.

The field of kiruv has always been a medium for ideas to enter into the Orthodox community, for culture to be brought in in ways that the community finds more palatable halachically and hashkafically. It wasn’t surprising to me that the popularization of social science within the frum world came through the kiruv world.

JA: Can you give a concrete example of how data can be used to change or redirect an OU program?

MW: One basic question we like to ask is—do our programs work?

We actually have a fairly rigorous definition for “work,” which is: Do they make an impact? Do they alter the trajectory of the community by comparison to a similar community without that particular program? In other words, can we attribute change in a population to the intervention we’ve provided?

Since the OU is a 100-plus-year-old organization, there are many departments that arose at specific times to solve specific problems. Take NCSY, for example. In the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, American Jewry consisted of a large traditional community that sat somewhere between Conservative and Orthodox Judaism. We didn’t have the day school system that we have now. So we created the “National Conference of Synagogue Youth,” which had an outsized place in the religious experience of teenagers’ lives.

The Orthodox community—every community in fact—has always engaged in self-study. We love talking about ourselves.

Things change. Nowadays, we don’t have that large traditional community anymore. In fact, Conservative Jewry itself is shrinking dramatically; the average Conservative member is over the age of sixty. It’s a community that in many ways is an artifact of the twentieth century.

The day school movement transformed the landscape, and the Jewish world continued to change. As the societal realities evolved, NCSY evolved as well, and began meeting communal needs in different ways. In recent decades, NCSY started focusing on two distinct populations: minimally affiliated Jewish kids in public school and Modern Orthodox youth in day schools and yeshivot in need of inspiration.

Recently, the Center worked closely with NCSY to evaluate its Jewish Student Union (JSU) clubs. NCSY runs more than 180 JSU clubs on public and private high school campuses across the country. Over the past year, we embarked on a study of JSU in an attempt to redefine and narrow its goals. We ended up helping to re-engineer the JSU model and introducing the idea of surveying participants in the beginning and end of each school year. This will enable us to gauge the program’s effectiveness. While the new JSU design was supposed to be rolled out in the spring (plans were derailed by Covid), this is a very exciting new chapter for JSU. I can’t speak highly enough of NCSY’s leadership and staff in embracing this process and emerging as a model youth service organization.

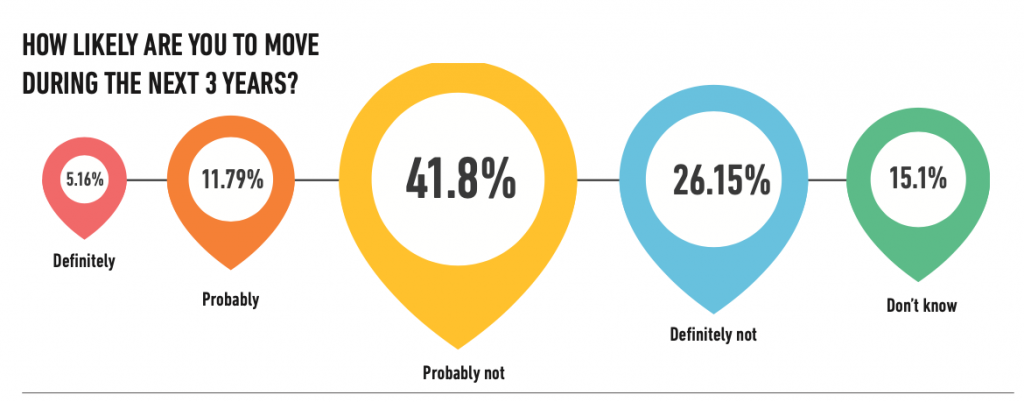

In a study by the CCR, which examined the effects of Covid on the Orthodox community, researchers analyzed four Orthodox communities: Atlanta, Dallas, New Rochelle/Scarsdale and West Hempstead. They received a 17 percent response rate from the over 700 households contacted. Of those that responded, approximately 17 percent would consider moving somewhere within the US or to Israel. With working from home as the new normal, many families don’t feel the need to live in the cities anymore. But most plan to stay where they are.

JA: Can you give an example of a study you worked on that has real-life implications for the Jewish community?

MW: We just conducted a Covid study, a portrait of four different Orthodox Jewish communities in the United States: Atlanta, Dallas, and Scarsdale/New Rochelle and West Hempstead in New York. We picked these four communities because they are similar to a range of other communities socioeconomically, which allows us to make some broader claims about what might be going on in similar communities. We have representative samples of each of those communities, and our study is longitudinal—in other words, we are tracking the same groups within the community over the course of three surveys, so that we see the change over time, which is really crucial.

We first sampled these communities in May, we finished round two in September, right before the chagim, and the third round was done in middle of October. That gave us different social contexts and different calendar contexts for understanding potential changes over time.

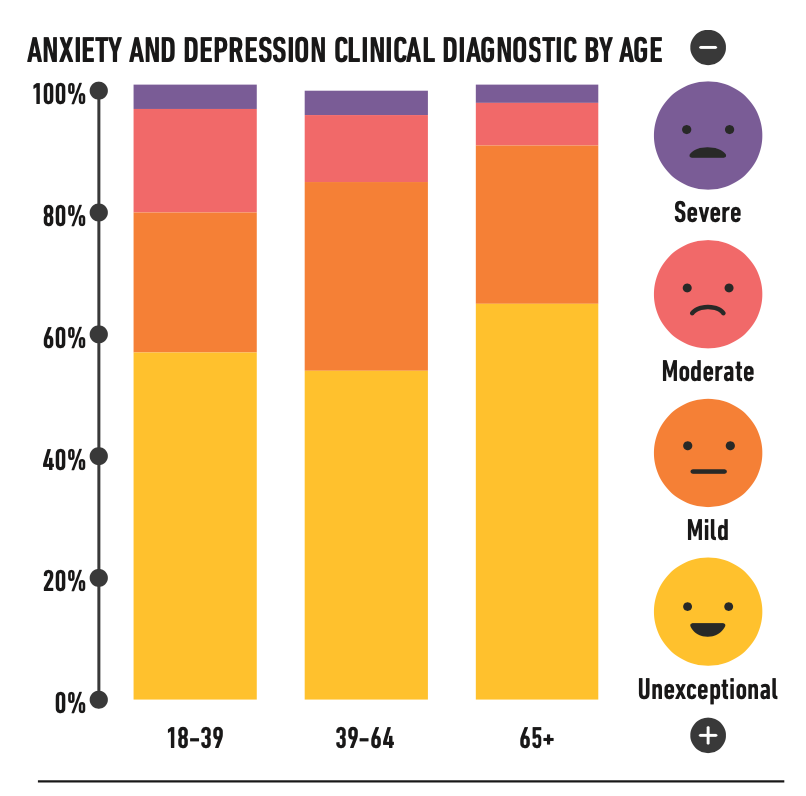

Research often questions popular consensus. We have all heard, for example, that seniors who are alone and isolated at home are having a hard time due to Covid. That’s something I think we all suspected. But our research on the various groups and how their lives have changed under the pandemic has actually shown that seniors are better off than some other cohorts. In our study, older adults didn’t report as high as others in terms of isolation or mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. This may be due to their being in a higher-income tax bracket or their having more assets, or more living space; they’re not sheltering in place in a small apartment with seven kids. The population that’s doing worse by far are one-income households—single parents with a few young children or younger adults living alone.

While the fact that single-parent families are having a hard time was not a surprise, the disparity between the age groups was a big surprise. Younger adults generally are doing worse. (See graph above.) While the OU cares deeply about the older adult population and while admittedly there are challenges among that population that need to be addressed, that cohort is, relatively speaking, doing okay despite the Covid challenges.

I do want to make one point very clear: the Center is not the arbiter of communal values. Those are theological, hashkafic and halachic decisions—which are for posekim and communal leaders to decide. What we at the Center can do is to inform the conversation by saying, “It’s great that we want to prioritize seniors, and we do, indeed, need to take care of that community, but in the context of Covid, it seems like depression, anxiety, stress and economic insecurity are hitting younger adults much harder than any other cohort in the American Orthodox world.”

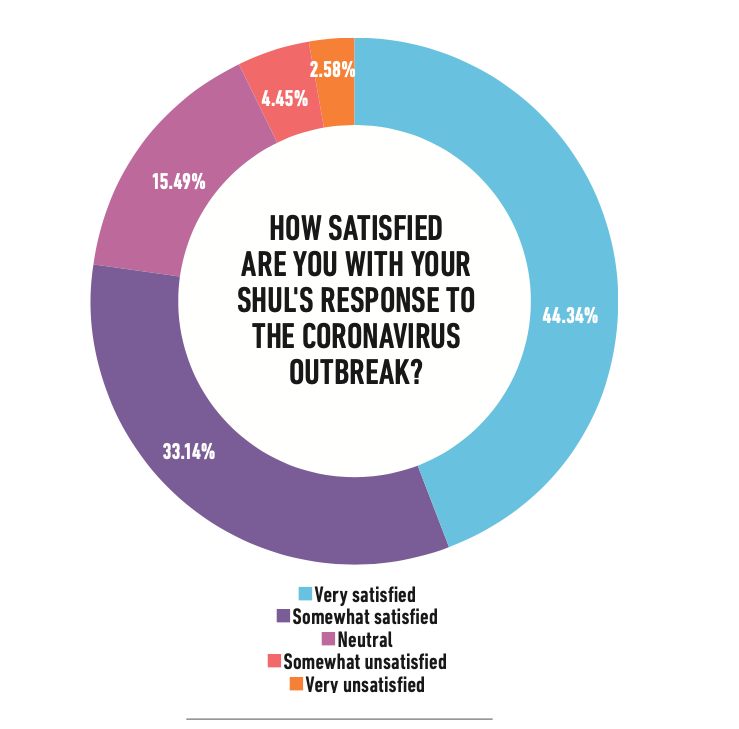

In the CCR’s Covid study, shuls scored well for measures taken to protect their congregants from Covid-19—enforcing mask wearing and social distancing, providing outdoor minyanim options, et cetera. The study indicated a satisfaction response rate of about 78 percent from surveyed households.

JA: Why did you decide to do a Covid study?

MW: We are in a new, unfamiliar environment, and there is a recognition that we don’t understand it. We certainly can’t understand it from our dalet amot, our own small social milieu, so we have to use social science to get at it.

If the OU is going to adapt effectively to this new context, we need information that will help us prioritize our programming and allocation of funds. Not only do we now know that this particular cohort [single-parent families] is suffering intensely during this time period, we also know how and why. That is really crucial, because we can provide helpful resources for them, such as career help, child care, et cetera.

JA: Can you give me examples of questions you might ask to determine whether or not a program is effective? Let’s assume a Jewish young adult goes on an Israel Free Spirit Birthright Israel program for ten days and then goes back to college in Wyoming. How would we know if there was an impact?

MW: There are a couple of ways you set up such a study. The most crucial aspect is to make sure you have a control group and a variable group. Birthright is great for this because there is a waiting list, so people on the list can serve as a perfect control group—a group of similar-minded people who are interested in the program but didn’t participate in it just yet.

We provide the control group and the variable group with a pre-questionnaire and a post-questionnaire. Additionally, we offer the post-questionnaire multiple times—three months out, nine months out, and then two years out.

We are interested in many different aspects that can help ascertain the impact of the program. Take, for example, the issue of people’s perceptions of the Orthodox community. We might ask: Do you think an Orthodox Jewish life is compatible with contemporary American society? When we ask that question before the trip and then again after the participants have spent a lot of time with Orthodox Jews, we would hope that there would be a change.

Studying how Covid has impacted people’s lives, researchers found a surprising disparity between the age groups. While the majority of respondents are not experiencing severe anxiety and depression, note the significant difference in the “moderate anxiety” column between the 18-39 age bracket and the 65+ age bracket. The younger set reports experiencing higher anxiety levels, perhaps due to factors such as less career stability or parenting young children during the pandemic.

JA: Is data commonly misused by the community, and if so, how?

MW: Yes it is, and in so many ways. One way is what we call “impact washing,” which is the notion that a customer satisfaction survey will tell you the impact of your program. An example would be a question such as: Do you feel you have more tools to work on your marriage after taking the XYZ Marriage Workshop? But because you don’t have the context of a pre- and post-study or a control group versus a variable group, you don’t know how the participants behaved beforehand or how a similar group that has not attended the workshop behaves, so you really can’t tell if it was your program that actually produced that outcome.

We see impact washing all the time in the Jewish community and in the nonprofit world generally, because there is such a demand to produce data to prove to funders that your intervention works.

Another common way of misusing data is through online surveys that are used to make representative claims (an accurate representation of the extent to which a phenomenon exists in the community) such as, for example, “33 percent of Orthodox Jews are X.” You cannot make representative claims without a very deliberate sampling model. The population to whom you are asking the questions is as important as the questions you are asking. You have to define that population; you have to be able to say, this is how this sample relates to this population. But with an online link that people pass around, you have no real idea who the population is.

JA: In the Orthodox community, there are segments of the population that tend to not use technology. Is this an obstacle in your attempt to do accurate research?

MW: It’s definitely a challenge from a research standpoint. The question of who has access to a study is one of the first questions that researchers should ask. People who are retired are generally easier to sample than those working two jobs, for example.

One of the ways that I’ve seen this challenge successfully managed—and this is just one example—is from an Australian Jewish study conducted a couple of years ago. A researcher went into the shtiebels and shuls in the Chassidic community there and set up a number of iPads, which had a brief set of instructions in Yiddish. The survey was translated entirely into Yiddish, and they set different hours for men and women to come in and complete the survey on the iPads.

The researcher also spoke in advance with the rabbanim in the Chassidic community and asked them what they would like to learn about their community, so that their questions could be included in the survey. In this way, the rabbanim could have buy-in to the process itself.

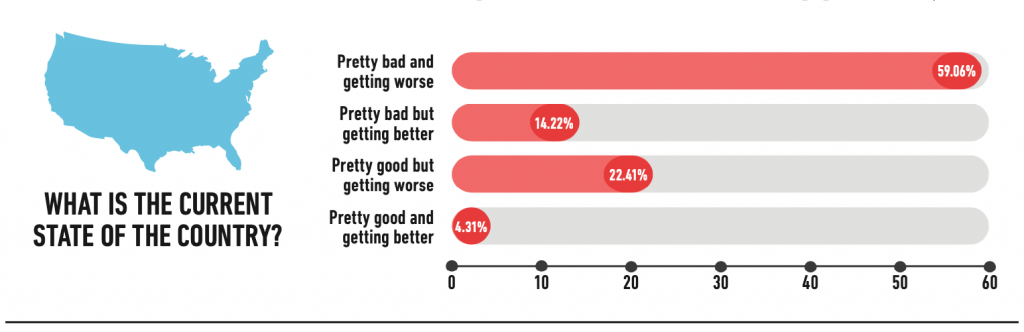

In the four communities surveyed by the CCR in June, September and October, the majority of respondents (about 82 percent) feel that the current state of the US—societally, politically, et cetera—is only “getting worse.”

JA: It would seem that every study is limited.

MW: Every survey is somewhat limited, but if we’re talking about large surveys such as those done by the Pew Research Center or the UJA-Federation of New York population study that is conducted every decade. Those are generally fairly good studies. They have not only done their due diligence to tell you the representative nature of their sample, but they can tell you—and this is crucial—how wrong they might be.

JA: What’s the most common question people ask you about your work?

MW: The most common question I get by far is: “How do you know you’re right?” I think many people are used to social scientists talking with authority about what it is they know. I’m actually much more comfortable talking with authority about what it is I don’t know. Defining your margin error, how confident you are in your findings, and what your study’s limitations are all essential for a researcher. In many ways, social science really is a discipline of humility.

JA: Is there a final message you would like to share with our readers?

MW: Ask hard questions and read critically. Use data to develop your own professional skills and growth. Bring due diligence to your work. Questioning and reading critically are tools of reflection that enable you to work more methodically and rigorously, which is especially important when you are working on behalf of the Jewish people. Those are the first two takeaways.

Also, it’s critical to remember that very few things happen without a backstory. There was Boy Scouts of America before there was NCSY. We, in the sense of humanity, have been doing youth service work for a long time. We’ve been teaching in schools for a long time. We’ve been serving college kids on campus for a long time. For Jewish communal educators in particular, there is already existing evidence from other communities about what might work and what might not work for the communities you serve. So the third takeaway is: Don’t reinvent the wheel. Don’t be afraid to look at what other people have done—and learn from it. This outlook, which the OU embraced, is one that I would love to see cultivated throughout the community.