The Kidney Connection: The Life-Saving Power of Jewish Unity

Michele London was brought up in a Reform home in Brooklyn, New York. After her son became paralyzed because of a back operation that went wrong, she gave up on God and Judaism.

Michele London was brought up in a Reform home in Brooklyn, New York. After her son became paralyzed because of a back operation that went wrong, she gave up on God and Judaism.

Years later, one morning, she woke up feeling dizzy. She had no sensation in her legs. Her doctor ordered her to go to the emergency room right away; blood results revealed that her kidneys had completely shut down. It wasn’t clear that she would last the night.

She went on dialysis the next day. She left her job of thirty-five years working as a city planner for the City of New York to spend three days a week, four hours at a time hooked up to a machine the size of a refrigerator, with two six-inch needles in her arm.

The kidneys, a critical part of the body’s cleansing system, eliminate waste products from the bloodstream as well as excess fluid. If they stop functioning, one can’t survive the toxin build up for long. Although dialysis serves as an artificial replacement for the kidneys’ filtration system, it is not as efficient as real kidneys. The average life expectancy of an individual on dialysis is five to ten years, whereas a live kidney transplant could give one decades, and offer a vastly improved quality of life.

While people are born with two of these fist-sized filter systems, one can function perfectly fine with only one kidney, making kidney donation a viable option for the donor and life-saving for the recipient.

London’s friend told her about Renewal, an Orthodox non-profit organization in Brooklyn that helps facilitate kidney matches within the Jewish community. After countless failed attempts at finding an appropriate donor, she was afraid to hope again, but she called Renewal and placed her name on its list of those seeking a donor.

Every time Esther Elbaum, a young mother of four in a Chassidic enclave in Monsey, New York, saw a newspaper ad publicizing the need for kidney donors, she felt a tug. She couldn’t stand to think that she could help someone suffering, yet her children were still very young. By the time her youngest turned two and a half, she decided to make the call.

Elbaum’s first match, a two-month-old infant, didn’t pan out; her kidney was too large. She was crestfallen. “We constantly need kidneys,” Renewal assured her, promising to keep her in mind. She heard back a few days later: a sixty-two-year-old woman was in need of a kidney. “Would you consider giving your kidney to her?” she was asked. Feeling hesitant, she asked to hear more about the critically ill woman. She was told the woman had a hard life. Her only child was born with Prader-Willi Syndrome, a rare chromosomal defect present at birth that results in a number of physical, mental and behavioral problems. Due to severe scoliosis (another common symptom of the disease), he required multiple surgeries, one of which accidently paralyzed him at age eleven. She had been taking care of him 24/7 for twenty-two years. During his long stays in rehab (sometimes up to a year), she would sleep on a lumpy cot, causing her to have multiple aches and pains and to consume significant amounts of ibuprofen, often known to cause kidney damage.

Elbaum’s first match, a two-month-old infant, didn’t pan out; her kidney was too large. She was crestfallen. “We constantly need kidneys,” Renewal assured her, promising to keep her in mind. She heard back a few days later: a sixty-two-year-old woman was in need of a kidney. “Would you consider giving your kidney to her?” she was asked. Feeling hesitant, she asked to hear more about the critically ill woman. She was told the woman had a hard life. Her only child was born with Prader-Willi Syndrome, a rare chromosomal defect present at birth that results in a number of physical, mental and behavioral problems. Due to severe scoliosis (another common symptom of the disease), he required multiple surgeries, one of which accidently paralyzed him at age eleven. She had been taking care of him 24/7 for twenty-two years. During his long stays in rehab (sometimes up to a year), she would sleep on a lumpy cot, causing her to have multiple aches and pains and to consume significant amounts of ibuprofen, often known to cause kidney damage.

Still unsure, Elbaum agreed to continue with the preliminary testing. In the interim, her mind ping-ponged between “yes” and “no.” She thought, “If I’m going to put my family through this, maybe I should wait for someone younger, in her twenties or thirties?” Then she thought, “What’s the problem? The woman could live to be one hundred. Young people pass away; what guarantee does anyone have? Who am I to decide who gets to live and who gets to die?”

Renewal called her back a few days later. “You’re a match, a great match. Are you happy?” She said she was. And she was.

A short time before the procedure, London found herself sitting in a waiting area packed with other transplant patients about to take some pre-op tests. Trying to contain her anxiety about the procedure and her fear that it might not really happen, she overheard a modestly-dressed young woman talking about being a donor and describing the recipient. She realized the woman was describing her.

“There were a lot of tears and emotion,” says Elbaum. “Michele had tried in so many ways to get a kidney, with so many disappointments. I told her it’s going to really happen this time.”

London could never have imagined her nightmare would end this way, and that she would become so intimately connected to a woman from a world so different from her own. “This young [Chassidic] woman with four small children was willing to make such a sacrifice for someone she didn’t know,” says London. “I asked, ‘How am I ever going to thank you for this?’ and Esther replied, ‘How am I ever going to thank you for giving me the chance to do this mitzvah?’”

Shortly after the transplant, London’s son passed away unexpectedly. London decided to give him an Orthodox burial. “Having Esther in my life gave me back my faith in God. Without it, I would have never survived. I could have still been on dialysis, with no faith and my son dying. What would have happened to me?”

Elbaum, who doesn’t drive, took a bus, a train and a ferry to attend the levayah (funeral) in Staten Island. “Michele became like my sister,” says Elbaum. She sent her new sister an e-mail, “If I were able to, I would give you my heart.”

The Kidney Matchmakers

According to Rabbi Josh Sturm, Renewal’s director of outreach, the organization hears from about two to three patients a week, and maybe one donor. “It’s hard to keep up with the pace,” he says. Close to 5,000 Americans die waiting for a kidney each year, as the national average wait time for a kidney is five to seven years. Live kidney donation is ideal. “[Live kidneys] last twice as long as kidneys from deceased donors,” says Rabbi Sturm. “They also work instantly after the transplant over ninety-five percent of the time, whereas kidneys from non-living donors can take a while to start functioning.”

Working to save Jewish lives through kidney donation, Renewal has facilitated 345 transplants since its inception in 2006, and the average wait time for those on its recipient list is six months. In 2015 alone, the organization facilitated sixty-four transplants, representing 60 to 70 percent of all altruistic live kidney donations in New York State. (Several hundred Americans donate kidneys to strangers each year.) The majority of Renewal’s donors are Orthodox; however, Renewal’s recipients come from across the entire Jewish world.

Renewal furnishes funds for transportation to and from medical testing for donor and recipient, and provides food and lodging for family members who wish to stay with the donor or recipient during his or her hospital stay. It also provides donors with up to a month of lost wages. The recipient’s insurance covers all the costs of the actual procedure, including the donor’s end.

Kindness in the Online Age

Kindness in the Online Age

In today’s interconnected world, e-mail campaigns can have a profound impact on the success of kidney matching. Rabbi Sturm shares the story of a woman named Shayna,* who was seeking a kidney for her forty-year-old son with special needs. She contacted Renewal and initiated an e-mail campaign to find a donor for her son. The e-mail sailed around the world—from Shayna’s community in Miami to Baltimore, and subsequently to the dean of a seminary in Israel, who forwarded the plea to hundreds of the institution’s alumni. The campaign not only helped Shayna’s son find a donor, it also succeeded in finding kidney donors for two others on Renewal’s list, thereby saving three lives with one e-mail.

In addition to Renewal, there are a few other Jewish organizations dedicated to connecting kidney donors to recipients and to educating the population about kidney donation. In Israel, the non-profit organization Matnat Chaim educates individuals about kidney donation and provides support to donors. Its extensive web site with resources and information provides education about every step of the process.

Two online resources for kidney matchmaking were created by those intimately knowledgeable about the topic—donors and recipients. Chaya Lipschutz created KidneyMitzvah, a web site that aims at spreading awareness and providing information about kidney donation. Lipschutz, from Brooklyn, donated a kidney herself in 2005. Ever since, she has worked to match donors with recipients and is responsible for many successful matches. Her web site contains information about kidney donation, resources for potential donors, and inspirational stories of successful matches.

Kidney for Harry is a Facebook page run by Harry Burstyn, a kidney recipient. The page is part support group for those waiting for kidneys, part inspiration to encourage others to donate. Burstyn’s page also shares stories and statistics about other live transplants and organ donations.

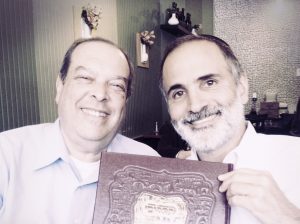

Mitch Bornstein (left) and A. J. Gindi, six months after A. J. donated a kidney to Mitch. The two are holding a Sefer Tehillim that Mitch had comissioned for A. J. Courtesy of A. J. Gindi

Multi-Cultural Kidneys

No one knows how A. J. Gindi, a Syrian Jew and resident of West Long Branch, New Jersey, first got into the Renewal computer system. He suspects it had something to do with his participation in a community bone marrow drive. A year and a half after the event, he received a call informing him that he would receive a blood kit to determine if he was a match for a potential kidney recipient. The kit arrived; he put it aside. They called again, instructing that he take the samples to the local lab. He complied.

A month later, he got another phone call: Renewal had found a possible match. Would he be willing to donate? He said, “Yes, he’d love to help someone.” Then fifty-two, Gindi underwent a battery of tests to ascertain if he was physically and psychologically capable of donating a kidney. Only thirty percent pass. He passed.

Dressed in his hospital garb, he met Mitch Bornstein, the recipient, the morning of the surgery. The sixty-year-old resident of Queens, New York had struggled with type 2 diabetes since his forties and high blood pressure since his teens, the two main causes of renal failure. His kidneys started to decline. He lost all desire to eat and he couldn’t sleep. He went on dialysis. “It was horrible; something I truly wouldn’t wish it on anyone,” Bornstein says.

He and his wife put the word out for a donor. They advertised in Jewish newspapers, printed flyers, sent e-mails and made phone calls. Gindi’s kidney was a perfect match.

“What can you say to a person who is going to save your life?” says Bornstein, recounting his first face-to-face with his donor. “There’s no way to describe it. We just embraced and I cried. We may come from different places, but we have so much in common. Jews help Jews and that’s why we are still here.”

The two maintain contact via text and frequent phone calls. Their families got together at the Gindi Shabbat table to celebrate the one-year anniversary of their operations. No doubt, Bornstein appreciated the kibe hamda (Sephardic cholent); he also enjoys joking about his new kidney. Right after the surgery he asked, “Since I have a Syrian kidney, can I eat rice on Pesach?” And when people inquire about his background, he can’t resist revealing that he’s “part Syrian.”

“Hashem put me into this world to help as many people as I can, with my time, my heart, my mind and my body,” says Gindi.

Kidney donor Yoel Usher Labin with recipient Robert Sendzischew, as they both recuperate at Mount Sinai Hospital. Photo: VINnews.com/Rafael Lopez JR

Defying Stereotypes

Robert Sendzischew, forty-one, suffered from high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes. He suddenly found it difficult to breathe, and the air felt increasingly and unbearably humid. His kidneys had ceased functioning, causing water to collect in his lungs. He immediately went on dialysis.

Sendzischew remembered a lecture he had attended two years prior to the diagnosis that was given by Lori Palatnik, a prolific speaker, Jewish outreach professional and kidney donor. She described donating a kidney to a Jew she never met as being the greatest experience of her life. Sendzischew and his wife, who were very moved by the talk, had no idea how relevant that speech would become.

He called Renewal to join its recipient list and began the required testing. Within weeks, a Satmar chassid had begun his own testing to qualify as a donor. By the time Sendzischew signed the paperwork, the shidduch was in the works. Sendzischew had hoped to wait until after his son’s bar mitzvah celebration, but the donor wanted to do the surgery quickly.

“When a mitzvah comes your way, don’t delay it,” says Yoel Usher Labin, Sendzischew’s donor, quoting a gemara. A Yiddish journalist living in Boro Park, Labin sent out an e-mail to family and friends on the morning of the surgery, his thirty-second birthday: “Today, the eighteenth day of Kislev . . . I received a treasure, the brilliant gift of life. Today . . . I’ll be the lucky one again, by giving the gift of life to a fellow [Jew] . . .”

To assuage his young children’s concerns, Labin bought a doll with removable organs and explained what the kidneys do. “So that person has no kidney and you have two,” said his son, who was six at the time. “It’s like I have two lollipops and another kid has none. The best thing to do is give one to your friend.”

The day after the surgery, Sendzischew shuffled down the hall to his donor’s room, three doors away. “I had no idea what to expect. I didn’t know what kind of Jew would do this.”

A few months later, at the packed bar mitzvah hall, a group of jubilant participants lifted Sendzischew and his son aloft upon their chairs; another group simultaneously lifted up Labin, in his distinctly Chassidic garb, beard and peyot. The guests formed long lines to thank him personally. He made a profound impression on one guest in particular.

“Whenever I saw someone who looked like you do, I would get a very negative feeling,” said the female guest. “Now that I see you and know what you’ve done, I’m changing my mind.”

The significant number of living donors in the Jewish community has not gone unnoticed in the medical community. “I am always pleasantly surprised to see how many people come out to the donor drives,” says Dr. David Serur, medical director of kidney and pancreas transplantation at the Rogosin Institute of Nephrology, affiliated with New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell, in New York City. “It would be great if this could be replicated around the country in different communities.” After twenty-four years in the field, he’s still awed by the transplant process. “You could take a chronic disease and make it one hundred percent better through the generosity of another. Kidney donors are super heroes; there are no other people I hold [in higher] regard.”

Practicing What He Preaches

Rabbi Larry Rothwachs, rabbi of Congregation Beth Aaron in Teaneck, New Jersey, had a dilemma. Donny Hain, a man in his community, desperately needed a kidney donor; dialysis was taking its toll. Hain’s brother asked the rabbi to run a program in the shul to promote the idea of kidney donation and alert them to Hain’s plight. Rabbi Rothwachs, who had never met Donny, jumped at the chance and began planning the event. However, he couldn’t shake the thought that he would be presenting the virtues of donating a kidney, while never having considered doing it himself. Rabbi Rothwachs thoroughly researched the topic, spoke with past donors and physicians and decided it made sense to do it. He consulted with his wife and his rabbi and then initiated the screening process. Within two months, he was on the operating table. Although he was prepared to give his kidney to any Jew in need, fortunately, Rabbi Rothwachs was a perfect match for Hain.

The two unexpectedly met at the pre-op testing. “It was emotionally overwhelming, in a positive way,” says Rabbi Rothwachs. “It put real meaning and purpose into the entire process, which until then had been more technical. Now there was a face behind it. What this was really about was having the opportunity to save a life. It gave me a tremendous surge of chizuk.”

While in the hospital, Jewish kidney donors whom Rabbi Rothwachs had never met before stopped by to share their experiences. “The night of my surgery, a chasid walked to the hospital from New Square and someone else came the next day,” says Rabbi Rothwachs. “You definitely feel you’ve come into a special family.”

Rabbi Rothwachs’ Shabbat HaGadol derashah reflected his own transformation. “I told the congregation about a part of the screening process that entailed twenty-four hour urine collection. Never in my life had I given a thought to how much one’s body produces. It was eye-opening, awe-inspiring. Months have passed since I took that test and every Asher Yatzar of mine since then has been different.” Since his speech, several community members have expressed interest in possibly becoming kidney donors and some have started the screening process.

“You can talk to your children about the value of chessed, and what it means to give,” says Rabbi Rothwachs, “[but] I have a feeling [that my children] learned a lot more from this one act [of donation]. My only regret is that I can’t do it again.”

*Pseudonym

Bayla Sheva Brenner is a freelance writer and a regular contributor to Jewish Action. She can be reached at baylashevabrenner@outlook.com.