Inside the Mind of the Gabbai

Many gabba’im use a card index file to keep records of members’ Hebrew names and the dates on which they received an aliyah. Photo: Erica Berger

Master of ceremonies, diplomat, event coordinator, social worker, greeter, mediator, mentor—these are just some of the hats that a shul gabbai wears. He has to be both a strategist and a tactician, sometimes patient and sometimes resolute, in some circumstances a heavyweight, in others a charmer. He has to be familiar with the intricacies of the halachot of tefillah, of kri’at haTorah, and of the Jewish calendar, and he has to be a master of interpersonal skills.

The gabbai’s responsibilities are multitudinous. On his arrival in the synagogue, he checks the aron kodesh and the sefer or sifrei Torah to be used that day. He selects the ba’alei tefillah to lead the various parts of the service. He allocates the many honors related to the Torah reading: who will open and close the aron kodesh, who will be called for aliyot, as well as for hagbahah and gelilah, and who will read the haftarah. He stands at the bimah, calls their names, and says the Mi Sheberach for them following the reading. If there is a simchah to be celebrated, he must say one of several special Mi Sheberach prayers as befits the occasion. If a baby girl was born in the community, it is the gabbai who announces what her name will be when the father gets an aliyah. He recites the prayer for those who are sick and, at the appropriate times, the Kel Maleh Rachamim when a congregant is observing a yahrtzeit. And when newly bereaved aveilim come to shul to say Kaddish, it is often the gabbai who gently and sensitively shepherds and guides them.

As the service progresses, he must keep a watch for any distinguished guests, so as to properly honor them. He must be aware of any members who have a chiyuv, such as a yahrtzeit that day or in the coming week, or who are celebrating a milestone in their family, and must check to see that they are actually present. If there is any clash of equally eligible chiyuvim, he must negotiate a solution that is acceptable

to all parties.

Meanwhile, the gabbai must be on the alert for all the intricate nuances of the service that are triggered by the calendar, such as which haftarah to say and whether or not to say Av HaRachamim or, at weekday services, whether or not to say Tachanun. If there is a variation in the usual order of the service, e.g., the addition of Ya’aleh Veyavo on rosh chodesh, the gabbai reminds the congregation about it either with a klap (banging on the desk—see the sidebar on page 28), or by calling it out or both. He is also the keeper of his shul’s specific nusach and minhagim, and he must make sure that they are faithfully adhered to.

And while he is involved with all of this, he must keep an eye on the level of decorum, as well as on the clock, monitoring how the service is progressing, not too fast, not too slow.

Why would anyone want to take on a role with such an overload of responsibility, with a need for expertise in such seemingly picayune details, with such potential for error or offense, and with such susceptibility to criticism? Yet when asked in a recent informal survey1 of gabba’im, “How much do you enjoy being a gabbai?,” the overwhelming majority gave answers such as “very much” or “immensely.” Yehudah Powers, former gabbai of a minyan in Manhattan, says he “loved it, absolutely loved it.” Ari Ganchrow, of Teaneck, New Jersey, agrees. “Most of the time it is a big thrill,” he says. And when asked for how long they would want to stay in their positions, nearly half responded “forever!”

Most gabba’im say they learned on the job, although some had their fathers or other gabba’im as role models. In some shuls the term of a gabbai is limited and is subject to election by the membership, but in many he can continue for as long as he wants, or perhaps until an objection is raised. There are some, however, who feel trapped in their positions. “No one seems interested in stepping up as my replacement,” writes Effie Love of Queens, New York. Responding from the UK, another gabbai echoes his frustration. “There is no queue of willing replacements,”

he says.

Filling the role of a shul gabbai demands a lot of patience, a thick skin, an organized mind, and an altruistic nature.

Recruiting volunteers to take on roles in the synagogue seems to be a universal problem. Aaron Alweis, a gabbai in Binghamton, New York, points to a major frustration shared by many others—getting people to agree to lead the service. “People whom I know are capable of davening for the congregation consistently refuse to do so,” he reports. “There are a few who will go up if asked, no matter what,” observes another longtime gabbai, “but as for the rest—it can be like pulling teeth. Trying to create a variety of ba’alei tefillah is very challenging.”

So what do gabba’im look for in a ba’al tefillah on a Shabbat or yom tov? Asked to rank the necessary qualities, they put familiarity with the correct nusach of the day at the top of the list, followed in order by accuracy of reading Hebrew, a pleasant voice, kavanah, reasonable speed, using well-known melodies, popularity, and then level of personal religious observance (perhaps surprisingly) most often in final place.

For a ba’al keri’ah, it is no surprise that accuracy tops the list of desirable qualities, followed by a pleasant voice and a good pace, with level of observance again coming in last.

Monitoring the accuracy of the Torah reading is almost a competitive sport in some synagogues, with many zealots poised to call out a correction at the slightest hint of error. In fact, when asked whose job it really is to correct the ba’al keri’ah, one gabbai answered “everyone’s,” while another said it was “whoever shouts loudest.” But although in some shuls the rabbi alone takes on that responsibility, more often than not it is one of the gabba’im who must pay the closest attention to the reading.

Many larger congregations have a “ritual” or “religious” committee which sets the overall policy regarding the shul’s minhagim. But the majority of gabba’im report that they have complete freedom in making decisions about whom to honor, with just some occasional input from the rabbi or the synagogue president. “Over time, a good gabbai learns the quirks and needs of the members,” says David Zeffren of Los Angeles, California.

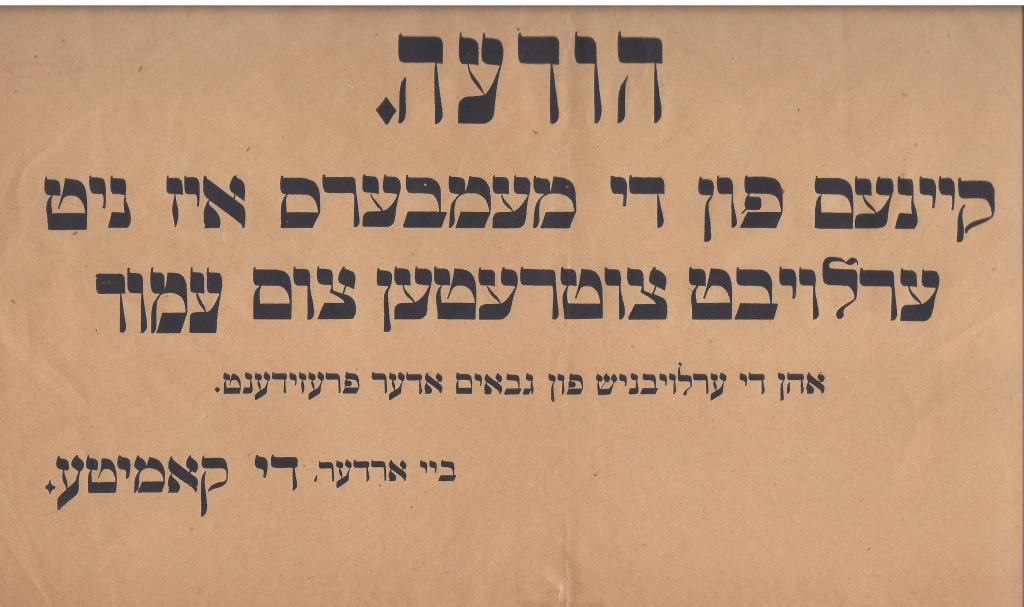

Early twentieth-century Yiddish sign from a synagogue in London’s East End. It reads: “Notice! None of the members is permitted to take the amud [i.e., lead the davening] without the permission of the gabba’im or the president. By Order, The Committee.” Courtesy of Alan Weisrose

But sometimes things can go awry, despite the gabbai’s best efforts. It happens, for example, when a member who is due for an aliyah shows up late. “Rearranging the aliyot on the fly can be very tough,” notes Steve Shach, who has acted as gabbai in congregations in South Africa, Nashville, Tennessee, and currently in Sydney, Australia. Another difficult situation can arise when a congregant who has a yahrtzeit or is celebrating a significant family milestone just assumes that the gabbai knows about it. Even though that is usually the case, there can always be instances of miscommunication, and if the congregant does not get what he regards as his due, the gabbai will hear about it, sometimes loudly.

In terms of allocating kibbudim, veteran gabbai Dr. Gerald Mayerhoff of Hollywood, Florida, and many others feel that “the most challenging time of year is the period of the Yamim Noraim,” when shuls are at their fullest. But as an example of an even more pressured scenario, numerous gabba’im cite those Shabbatot when there might be a bar mitzvah, an aufruf and a baby naming all on the same day, calling for all their strategizing, negotiating and persuasive skills. But there may simply not be enough kibbudim to go around. “Making hard decisions can sometimes even cost you a friendship,” laments Ari Ganchrow.

Yet there’s also another side to the coin. “I enjoyed working with families celebrating semachot,” says Dr. Chaim Himmelfarb, who served as a gabbai for over a dozen years in various congregations. “It’s a tense time for these families, but working together with them to organize the kibbudim was usually much appreciated.” Adds Chaim Kiss of Teaneck, New Jersey, “The most satisfying part is when they say thank you.”

When asked whether they think that their community appreciates how much effort and judgement goes into what they do, many gabba’im feel that they are usually taken for granted. But speaking of his experiences in shuls in Boston, Massachusetts and Passaic, New Jersey, Rabbi Adam Dubin feels that “the regulars certainly do appreciate it, and they acknowledge it.” Putting it in perspective, Bart Nierenberg of Longmeadow, Massachusetts, a gabbai for over twenty years, feels that “most people are not very aware of the amount of behind-the-scenes work and stage management that is required to do a good job and to keep services running smoothly. We’re at our best when you barely notice that we’re there.”

When they are criticized, most gabba’im say they can handle it well if they agree they did indeed make a mistake, but if they feel it is unwarranted, many will take it to heart and, after the service is over, even take it home with them.

How do they balance the demands of their roles in shul with the needs of their families? On the whole, it seems that most of their spouses and children share a sense of pride, as long as it does not take them away from home for too much time. Those with young children, however, feel a pull. “It doesn’t allow me to sit with them in shul as much as I would want,” says Alan Weichselbaum of Lawrence, New York. Also from Lawrence, Mordechai Schrek feels similarly, but adds, “It’s important to imbue in children the importance of being involved in communal endeavors, especially in a shul.”

It is indeed a great sense of commitment to the community that motivates gabba’im. Many emphasize the need to “maintain high standards for ba’alei tefillah and kri’at haTorah.” Robert Rubin of Livingston, New Jersey, derives great satisfaction in “knowing that I made a difference in people’s lives by helping to give them a positive shul experience.” And one after another, gabba’im say that what is important to them is to make everyone feel welcome and included, to have the service run smoothly, and “to get it right.”

Still, however much he may be focused on the needs of those around him, the gabbai also has his own obligation to daven and to fulfill the mitzvot of the day. Is it possible for him to daven with at least a modicum of concentration while his mind is chock-full of all the myriad tasks he needs to handle? With admirable frankness, most gabba’im admit that, unless they attend an earlier minyan first, or daven ahead at home, it is indeed extremely hard. But with equally admirable boldness, they are nearly unanimous in stating that the sacrifice is absolutely worth it. David Zeffren’s attitude is typical: “While my personal tefillot may suffer, there is great reward in serving the tzibbur.”

Filling the role of a shul gabbai demands a lot of patience, a thick skin, an organized mind, and an altruistic nature. Motivated by a sincere desire to make the shul service pleasing and acceptable to Hakadosh Baruch Hu and to all who attend, the gabbai is the linchpin around whom the whole shul revolves. So what goes through a gabbai’s mind as he enters the synagogue? More than anything else, how privileged he is to be the one who orchestrates and conducts it all.

Note

1. The questionnaire was circulated informally, through social media and word of mouth. Responses came from gabba’im in large and small communities across the US, in Israel, in the United Kingdom and elsewhere. I want to thank all those gabba’im who took the time to complete the questionnaire and who were willing to share their experiences, feelings and opinions with me. My thanks also to those who helped me select the topics to be dealt with.

David Olivestone, a member of the Jewish ActionEditorial Committee, lives in Jerusalem. Among his previous contributions to the magazine are articles on what goes on inside the minds of the ba’al teki’ah, the chazan, and the kohen.