God, Sod and the New York Yankees

I will never forget old Jake. A likable and generous contributor to our Atlanta synagogue, he was invited one Yom Kippur to mount the pulpit and open the Holy Ark during the recitation of the awesome Unetane Tokef prayer. There he stood right next to me, his rabbi, solemnly intoning the words “Who shall live and who shall die, who by fire and who by water . . . who shall live out his years, and who shall not. . . .” I had never known Jake to take his Judaism very seriously. For him the true god was baseball, and the New York Yankees were his chosen prophets. But here was Jake, eyes glued to the page, gently swaying back and forth in rhythm with the chanting of the cantor.

I will never forget old Jake. A likable and generous contributor to our Atlanta synagogue, he was invited one Yom Kippur to mount the pulpit and open the Holy Ark during the recitation of the awesome Unetane Tokef prayer. There he stood right next to me, his rabbi, solemnly intoning the words “Who shall live and who shall die, who by fire and who by water . . . who shall live out his years, and who shall not. . . .” I had never known Jake to take his Judaism very seriously. For him the true god was baseball, and the New York Yankees were his chosen prophets. But here was Jake, eyes glued to the page, gently swaying back and forth in rhythm with the chanting of the cantor.

The prayer ended and Jake deferentially closed the Ark. As he shook my hand, he whispered into my ear, “Yankees 4, Dodgers 1, end of the fifth.” For Jake, the fact that his team was winning the World Series was the closest thing to heaven on earth.

So it is with true sports fans. Neither rain nor snow nor heat nor gloom of night—nor the solemnity of Yom Kippur—shall stay these fans (read: fanatics) from the main business of their appointed rounds: to get the latest score. Who shall live and who shall die is of little moment. What really matters is who shall win and who shall lose.

When Jake was standing there so respectfully, he was no doubt praying that the God of Israel allow his beloved Yankees to triumph. And in his unshakable belief that a little Divine bribery never hurts, he undoubtedly promised the Creator that if he won his bet, he would contribute some of the earnings to the synagogue.

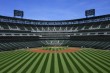

I thought of Jake when I saw a recent advertisement in the New York Times about the old Yankee Stadium. As every sentient being surely knows, the big news of this past summer is that the New York Yankees are no longer playing on their old grounds, the classic “house that Ruth built.” Instead, they are now cavorting in their sparkling new ball park, while the old stadium is being reduced to rubble.

True Yankee addicts are beyond comfort. The old stadium, home of Babe Ruth and Joe DiMaggio and Lou Gehrig and Mickey Mantle, is no more. Yankee Stadium, which housed more World Series championships than any other ballpark in baseball history, is dead; long live Yankee Stadium.

But the Yankee management, ever inventive, has found a way to address the discontent of its fans. In a stroke of marketing genius, they are selling bits and pieces of Yankee Stadium as memorabilia. Not only can fans now own a genuine Yankee trash can for $200, or an authenticated brick for a mere $150, but they also have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to obtain mounds of dirt from the infield and freeze-dried sods of grass from the outfield. In this way, whenever despair threatens to overcome the faithful, they can gaze lovingly at the good earth, even finger the grass on which their heroes trod in the glory days of yore and thereby derive some small measure of solace and consolation from their loss.

For only $199 a loyal Yankee fan can obtain photos of past Yankee greats, plus capsules of bona-fide, unadulterated Yankee Stadium dirt.

Clods of earth for the faithful: the mind reverts back to an ancient Jewish religious custom. While it is desirable for a Jew to be buried in the holy soil of Israel, not everyone can manage this. Instead, Jewish burial societies—the various chevra kadishah groups around the world—maintain little vials and bags of earth from Eretz Yisrael, which are inserted into the casket alongside the deceased. Thus, even if the person is being interred in Paris, London or Los Angeles, he or she is at least symbolically being buried with holy soil.

Is there an interface between sports and religion? The Yankee sod is not really Yankee Stadium, and the bag of Eretz Yisrael earth is not really the Holy Land, but what really matters is what they represent to the faithful, who require symbols and rituals. Of course, for the believing Jew the mitzvot he or she performs are more than mere symbols. The tefillin that are donned daily; the mezuzah that is placed on the door; the Shabbat that is observed; the kashrut that is maintained; the charity that is tithed; the loving kindness that is practiced—these mitzvot are all physical reminders of the Creator. Ideally, the commandments are designed to help the Jew connect with the Commander, and to enable him to be in contact with the God for whose perfection and presence he yearns.

True Yankee believers would recoil at being classified as religious. Nevertheless, as loyal fans they fully understand that in baseball, as in religion, there are strict rules that govern the game; there are boundary lines and certain things are fair and other things are foul. But above all else, these fans, as they remember the heroic and glory-filled history of the Yankees, also yearn to connect with that history, with something above them and with that ideal of perfection represented by the Yankee dynasty.

For the Yankee heroes of old were the high priests of the game, consummate representations of athletic perfection. DiMaggio, for example, hit safely in fifty-six straight games in 1941, played the outfield with consummate grace and could throw a strike from center field. Gehrig, known as the Iron Horse, played—and starred—in 2,130 consecutive games. Mantle was baseball’s batting champion for years on end. Babe Ruth hit sixty home runs in one season—and none of these players had ever heard of steroids or performance-enhancing drugs. The New York Yankees were a symbol of power and majesty, inspiring awe, fear and reverence in anyone who opposed them. Their pin-striped uniforms were the hallowed priestly vestments that, it was said, could transform even pedestrian players into great stars. The field they played on was as close to sacred ground as a Yankee fan could reach on this earth.

Now all that is gone. Just as the believing Jew wants to be in eternal contact with holy soil, even if it is only a vial of Jerusalem earth, so too the fervent sports fan wants to be in eternal contact with his own holy soil, even if it is only a capsule of dirt from the Yankee infield. And just as the traditional Jew places on his wall an image of Jerusalem’s Western Wall and gazes longingly at what was once the site of the Holy Temple, so too the traditional Yankee fan can now gaze longingly at a small remnant of what was once baseball’s most sacred shrine.

One hesitates to look for hidden meanings where there might be none, but one finds himself musing about this inscrutable universal preoccupation with earth and dirt that seems to cross all natural boundaries. When a fan caresses the dirt from the Yankee infield or a sod of grass from the outfield, does that awaken in him some inchoate identity with the sources of his own being, with his origins and with his destiny? In some circuitous and convoluted way, is this for him a subliminal reminder of the Creator informing Adam that “dust thou art, and to the dust wilt thou return”? Yankee management would no doubt scoff at this reading.

Inchoate and subliminal matters aside, old Jake did ultimately return to the dust. Possessed of a religious passion for sports, he surely accepted with good grace—on his heavenly judgment day—the true facts of religious life, and now understands who the real winners and losers are. And since his local burial society, as is its practice, surely interred him with the requisite sacred soil, I pray that his peace was not overly disturbed when he realized that the vial of earth next to him did not emanate from Yankee Stadium, but from a somewhat holier place.

Rabbi Feldman was rabbi in Atlanta, Georgia, for forty years. He is the former editor of Tradition magazine, and the author of nine books.