Frum and Funny on Twitter: Sharing Insider Culture with the Outside

Zvi Hershcovich, a Montreal-based marketing professional by day and comedy writer by night, had been searching online for a particular routine by one of his favorite comedians, Wendy Liebman, when he found her on Twitter. He made an account and began conversing with several comedians he liked. In the process, “I discovered Twitter was a perfect place to drop original, frum humor content,” he says.

Posting as @cholentface, Hershcovich is doing what a growing number of other Orthodox Jews are doing on this social media platform: mining humor from the excesses, peculiarities and ironies that abound in Orthodox life.

For example, @cholentface: *gazing at the horizon with my son* ME: *squinting into the distance* Kid, one day the rain will stop and we’ll finally be able to take down our Sukkah. And that day will be a Shabbos.

And @cholentface: I feel like it’s kinda hypocritical of the Marvelous Middos Machine to put out a song about Zerizus and then release their next album twenty-five years later.

A former Lubavitch shaliach who had been stationed in Stavropol, Russia for two years, Hershcovich launched his first humor escapades back in yeshivah with an underground humor paper, the Loshon Hara Daily. Over the years, he has written satires, screenplays and stand-up routines for other people. With a growing fan base on Twitter (4,700+ followers), he’s beginning to get stand-up gigs for himself.

A former Lubavitch shaliach who had been stationed in Stavropol, Russia for two years, Hershcovich launched his first humor escapades back in yeshivah with an underground humor paper, the Loshon Hara Daily. Over the years, he has written satires, screenplays and stand-up routines for other people. With a growing fan base on Twitter (4,700+ followers), he’s beginning to get stand-up gigs for himself.

Realizing the gap between the material he posts and the knowledge base of some of his fans, Hershcovich channels his inner shaliach and sends out automatic welcome messages to new followers, inviting them to ask him questions about content they do not understand. He also uses Twitter to share very entertaining yet touching stories (via multiple tweets) about unexpected encounters he had with Jews in Russia.

If you haven’t checked out the frum Twitterverse, you’ll be in for some good laughs, but you really need to be part of the “oylam” to understand the inside humor. Jokes and pointed observations abound about the dating world, stereotyped wardrobe and accessories of new yeshivah rebbes (including photos of thick-soled black shoes, a white shirt, an old-fashioned briefcase and a circa 2000 cheap watch), Jewish food obsessions, the competition to get into the best yeshivot and seminaries and assorted other pressures that are unique to the frum world. The GIFs that are increasingly de rigueur for popular tweets transform what might otherwise be a pareve statement into something hilarious. For example, Ari D (@aridPT) posted three GIFs next to one another, each of a young Tom Cruise running for his life in one of his action movies. The tweet: *me rushing to wrap up my tefillin before the gabai klaaps the bima to start r”c mussaf*

Those wading into this frum new world will feel like strangers in a strange land unless they have some notion of what the Siyum HaShas is, have seen a beit midrash at full tilt, and get the jokes by Rejected Feldheim Books

Those wading into this frum new world will feel like strangers in a strange land unless they have some notion of what the Siyum HaShas is, have seen a beit midrash at full tilt, and get the jokes by Rejected Feldheim Books

(@FeldheimRejects), whose entries include:

UH-NUH… UH-HUH: The Language of Washers

Simchas on a Budget: How to Throw a Passable Bar Mitzvah for Under $70,000

Explaining Mevushal Without Hurting Anyone’s Feelings

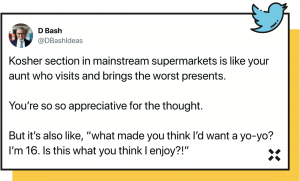

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin, the director of education for NCSY and a popular presence on Twitter (4,000+ followers), posts as @dbashideas. He’s enthusiastic about the benefits of having Orthodox Jews joking and commenting on this platform. “Until frum Twitter came along, frum Jews on social media were mostly stepping outside their culture and into someone else’s world,” he says. “Now, there is both an insider-outsider culture, where insiders can appreciate and interact with others who share their passions and concerns. It also creates a niche that increases the value of the insider culture.”

Others see more risk than reward. In a column published in Mishpacha magazine in November 2019, columnist Eytan Kobre articulated his concern about the direction of humor in the frum world. While acknowledging that humor fulfills a basic human need, he wrote, “We have a well-placed concern over engaging in leitzanus (scoffing), which is un-Jewish, prohibited behavior, as stated by Chazal (Megillah 25b), and depending on its topic, humor may also involve lashon hara, halbanas panim [shaming someone], and other prohibited types of speech.” Kobre pointed to a risk in joking about our lives as if it is just another lifestyle, albeit one “replete with all the most heimish, mehadrin trappings of ritual and custom and celebrations and foods and all the rest, but a lifestyle nonetheless, a sociological phenomenon supplanting a monumental spiritual odyssey.”

Engaging in “a steady diet of dissection of Jews’ religious life, combing one area after another in search of their giggle-producing oddities, has a cumulative effect on its readers, and not a good one,” he wrote. “It can make people feel self-conscious in their avodas Hashem when they ought to be filled with nothing but unself-conscious pride and joy.”

A few on frum Twitter have noticed the uptick in humor and questioned whether it is at the cost of serious discussion. As one tweet said, “FrumTwitter used to be a space of shared Jewish thoughts and educational ideas, interesting articles and occasional jokes. At this point, my timeline is basically taking any viral video/meme and turning it into niche satire of the Orthodox community.”

Naturally, this led to an immediate slew of counter-tweets, pointing out that while the number of jokes about frum life may be on the rise, so are Torah and Talmudic Twitter accounts, including several related to Daf Yomi.

The man who goes only by his initials of A.Y. and whose Twitter handle is @aimhumor, believes that overall, frum Twitter helps bring a little achdut to the Jewish world. His clever takes on frum life have brought him more than 2,600 followers and he knows that they comprise a broad spectrum of Jews from the left to the right. Because of that, A.Y. says, “I feel I have found my voice and try to mix it up, with both frum jokes and some more general Jewish jokes. I think it brings us all together, and I like having an impact on that.”

The man who goes only by his initials of A.Y. and whose Twitter handle is @aimhumor, believes that overall, frum Twitter helps bring a little achdut to the Jewish world. His clever takes on frum life have brought him more than 2,600 followers and he knows that they comprise a broad spectrum of Jews from the left to the right. Because of that, A.Y. says, “I feel I have found my voice and try to mix it up, with both frum jokes and some more general Jewish jokes. I think it brings us all together, and I like having an impact on that.”

For example, @aimhumor: How many shadchanim does it take to change a lightbulb? I don’t know, haven’t gotten an answer yet.

Awkward Bochur, otherwise known as @endimem_music, scored a lot of mileage from a slew of tweets about Dovy, “a cliché bar mitzvah bochur character” who is suffering under the welter of overbearing relatives whose inflated expectations all but ruin the milestone:

@endimem_music: *Uncle with nasty breath going in for the kiss* *Hands Dovy shnayim mikra set and shakes his hand too hard yanking his arm violently* Dovy *dies a little bit inside*

Jewish humor has long been notable for its sharp elbows and fearlessness at staring down dangers from both the inside and the outside. During a spate of violent attacks against Jews in New York, @aimhumor tweeted: Everyone’s been talking about carrying pepper spray but I’m gonna keep carrying my PAM spray that’s not aligned with the red dot. And when a web site called CampusReform announced that the Dickinson College student government voted to ban Sabra hummus because it was an Israeli product,

@dbashideas posted a screenshot from the announcement and tweeted: I’m sympathetic to calls to boycott Sabra hummus. Very poor consistency. Too pasty. Not Torah true. Not what we fought for over all these years.

Twitter in general is known as a medium where rhetorical smackdowns and the “cancel culture” hold sway. Among frum Twitter, it’s not uncommon to find jokes and remarks that reveal a certain cynicism, negativity and concern about serious, growing issues. For example, one finds many tweets related to the topic of going off the derech. Naturally, people have personal frustrations with some aspects of the frum community, but some jokes provoke arguments.

A.Y. says he tries to stay away from all that, and just be one of the nice, funny guys. “We have to be careful about what we post on Twitter, because it’s a very public place. I’ve deleted tweets which I felt didn’t live up to a certain standard. There is both a potential chillul Hashem standpoint and even a safety standpoint.”

Love it, hate it or indifferent to it, frum Twitter is growing by leaps and bounds. So far, most active frum tweeters are men, but women are tossing their metaphorical sheitels into the ring. Two of the most active women opt for anonymity. The woman who posts as @_nishei_, a young married woman who describes herself as “Orthodox and a little modern,” wants the freedom to say what she wants without repercussions and “without embarrassing my in-laws.”

Love it, hate it or indifferent to it, frum Twitter is growing by leaps and bounds. So far, most active frum tweeters are men, but women are tossing their metaphorical sheitels into the ring. Two of the most active women opt for anonymity. The woman who posts as @_nishei_, a young married woman who describes herself as “Orthodox and a little modern,” wants the freedom to say what she wants without repercussions and “without embarrassing my in-laws.”

@_nishei_: Do you ever become fleish at lunch time and then hate yourself for the rest of the day?

And @_nishei_: Last night I treifed up a fork and just threw it out instead of waiting 27 months to never kasher it.

Her profile picture—a female face, fully pixelated—points to her annoyance over the erasure of women’s images from most religiously right-wing publications.

While also staying anonymous, @vivushit has jokingly proclaimed herself the president of frum Twitter in her bio. She is a recent joiner with a goal “to show Jews at large who we really are and how normal and approachable we can be. And within the frum community, to show balance within observance, using humor.” Several of @vivushit’s tweets focus on shidduch issues, such as:

@vivushit: Headlining a short, embedded video of a Chassidic man in Jerusalem spray painting giant black “X’s” over posters displayed in his neighborhood, she writes: me going through the shadchan’s suggestions.

With its popularity booming, Bashevkin sees the frum social media world as “building a new repository for the Jewish community.” Conversations that previously might have remained closed in the back of the beit midrash or over coffee now have broad berth, inviting one and all to get in on the conversation, or the joke. Additionally, he sees an opportunity for a kiddush Hashem element.

With its popularity booming, Bashevkin sees the frum social media world as “building a new repository for the Jewish community.” Conversations that previously might have remained closed in the back of the beit midrash or over coffee now have broad berth, inviting one and all to get in on the conversation, or the joke. Additionally, he sees an opportunity for a kiddush Hashem element.

“Outsiders don’t just see us talking politics,” he says. “They see us using humor as a point of social cohesion. Chassidim, Modern Orthodox and all those in between are bonding together over our shared humor.” As for finding the balance between what could be leitzanus versus healthy, respectful frum humor, he recently tweeted this distinction: Constructive humor is spiritual; destructive humor is cynical. Learning the difference takes work, patience and graciousness.

Judy Gruen is a freelance writer in Los Angeles. Her latest book isThe Skeptic and the Rabbi: Falling in Love with Faith(2017).

The Serious Business of Laughter

The Serious Business of Laughter

By Judy Gruen

After months of careful planning, my first book, a humor diary called Carpool Tunnel Syndrome: Motherhood as Shuttle Diplomacy was published. I had been a journalist for many years, but I could hardly contain my excitement over this career milestone. I couldn’t wait to share my in-the-trenches stories of the funny side of motherhood with a wide audience.

But then things spiraled downward. My mother was diagnosed with end-stage cancer and told she had only weeks to live. Terrorism in Israel was claiming lives every week. Then terrorism hit home on the day I was scheduled for my first speaking engagement—September 11, 2001.

My goals as a humor writer suddenly seemed embarrassingly trivial, even self-absorbed. I asked my rabbi: Should I focus on serious writing because of the serious times we lived in?

“Absolutely not,” he said. “We need to laugh now more than ever. Your work is important.”

Even though humor had been a balm in my own life during dark times, I still couldn’t shake the feeling that my work was superficial. Then I received an e-mail that staggered me. It was from a woman who had read an excerpt from my book in Woman’s Day magazine while in a doctor’s waiting room. “I want you to know you saved my life today,” I read in total disbelief. “I was so depressed by my medical condition that I wasn’t sure I wanted to keep fighting. You made me laugh, and it made all the difference.”

The notion that a short column of light humor had “saved her life” seemed like an impossible overstatement, but she believed it. That was all that mattered. I never again doubted that writing for laughs was, in its own way, serious business.

This piece was adapted with permission from a longer article that appeared in Los Angeles’ Jewish Journal in June of 2019: jewishjournal.com/columnist/299911/laughter-is-serious-business/.

By Steve Lipman

Most Jews would consider Yom Kippur the most spiritual day on the Jewish calendar. A period of prayer and penance and abstinence, it is, Chazal say, ki’Purim, a day like Purim, which is a holiday of frivolity, practical jokes and laughter.

The rabbis recognized that laughter is holy, just as modern science recognizes laughter as a catharsis with many medical benefits. A good belly laugh, doctors say, is good medicine. Many hospitals welcome “clown doctors,” trained entertainers who roam the halls to take the minds of the patients, and their loved ones, off of their situations.

In the Nazi camps and ghettoes, prisoners looked forward to a joke that could, temporarily, relieve their daily horrors.

Humor enables us step back from an immediate problem and see ourselves from another perspective, as others see us. Humor allows us to see incongruities—as Sarah, giving birth at ninety, saw when she named her son Yitzchak, a name denoting laughter.

In the Torah outlook, laughter has a spiritual power. By laughing, especially at the darkest moments in our lives, and by helping other people laugh, we bring in some light, along with the recognition that the problem of the moment isn’t as big, or as permanent, as it may seem.

By laughing, we emulate God—“He who sits in Heaven laughs” (Psalms 2:4). The Torah and Talmud are replete with stories that reflect this concept.

The rabbis who were walking with Rabbi Akiva on the Temple Mount after the destruction of the Second Temple were understandably confused. They had just witnessed a fox darting through the ruins of the Holy of Holies, bringing them to tears. And Rabbi Akiva was laughing. The fox reminded Rabbi Akiva of the prophecy that after the future Churban, after Zion would be “plowed as a field,” old men and women would once again “sit in the streets of Jerusalem.” In other words, Jerusalem would be restored.

The presence of the fox was an indication that Zion was “plowed as a field.” Seeing the fox restored his hope that the remainder of the prophecy would be fulfilled as well—that old men and women would sit in the streets of Jerusalem. When he saw the fox, Rabbi Akiva’s faith was strengthened. And he laughed. Which did not diminish his sorrow at the destruction he witnessed. But he saw the big picture.

Laughter isn’t just the tool of stand-up comics. It’s the tool of rabbis trying to deliver a theological message. Rabba famously began his Talmudic lectures with a funny story.

It’s the tool of people showing concern for other people. Eliyahu HaNavi pointed to two nondescript men in a crowded marketplace as examples of individuals destined for the World to Come. “They are jesters,” he explained. “They cheer up people who are sad.”

For academic scholars who study humor, it is no joke. Jay Feinberg was seriously ill about thirty years ago, and Lorraine Weiss, an Orthodox woman in Brooklyn, wanted to boost his spirits. She decided to call him every Friday, in the middle of her erev Shabbat chores, and tell him a joke. “This is the first joke anybody has told me since I’m sick,” Feinberg told Weiss.

Feinberg underwent a successful bone marrow transplant.

He paid it forward, visiting other patients and making them laugh. Feinberg then founded the Gift of Life Bone Marrow Foundation, which has facilitated thousands of transplants—and helped save hundreds of lives—in the Jewish community.

Nothing is more spiritual than that.

Steve Lipman, a frequent contributor to Jewish Action, is the author of Laughter in Hell (New Jersey, 1991), a study of the role that humor played as a form of spiritual resistance among victims of the Third Reich.