The Mizinke Dance: Tradition, Folklore or Other?

Exploring One of the Most Puzzling Rituals at a Jewish Wedding

By Reuven Becker

In the “mizinke,” otherwise known as the “broom dance,” the parents of the bride or groom sit together, while family and friends form a circle and dance around them to the tune of an upbeat Klezmer melody, “Di Mizinke Oysgegebn, The Youngest Daughter is Given Away.”

Photo: Yehuda Boltshauser/Kuvien

“Did you get to see the mizinke tantz?” my wife asked me while we were driving home from a wedding.

“Yes,” I said.

“My friend Shaindy was standing right next to me. She feels it’s taken from the secular Yiddish theatre and adapted from some non-Jewish ritual. What do you think?” she asked.

A dance performed toward the end of the wedding, “the mizinke,” otherwise known as the “broom dance,” is increasingly popular in Orthodox circles. In the dance, the parents of the bride or groom sit together, while family and friends form a circle and dance around them to the tune of an upbeat Klezmer melody, “Di Mizinke Oysgegebn, The Youngest Daughter is Given Away.” Often a “crowning ceremony” takes place wherein the mother holds a broom and laurels are placed on the heads of both parents.

Admittedly, there is something about the broom sweeping and the donning of laurels that seems foreign to Jewish culture.1 Laurels in particular conjure up images of Greek gods. Nevertheless, the dance has become quite common at frum weddings.

How did the dance become part of the Jewish wedding? I thought it would be valuable to research the matter and learn the facts rather than speculate. I first checked my bookshelves. The two-volume classic Invei HaGefen by Rabbi Menachem Mendel Paksher had no mention of the dance. Neither did Nitei Gavriel: Nisuin by Rabbi Gavriel Zinner nor The Minhagim: The Customs and Ceremonies of Judaism, Their Origins and Rationale by Rabbi Abraham Chill.

Pursuing my research, I confronted my first big challenge: how do you spell the word? Is it “muzinke,” “mozinka,” “mizinke” or “mezynke”? I contacted Dr. Paul Glasser, former dean of the Max Weinreich Center for Advanced Jewish Study at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York. YIVO is the preeminent center for the study of East European Jewry and Yiddish. Dr. Glasser spelled the word for me in English (mizinke), and confirmed that it is indeed a Yiddish word meaning “the youngest daughter.” He didn’t know the history of the dance, but referred me to Chana Mlotek, YIVO’s music archivist, who has since passed away. “Certainly I know the song,” she said, referring to “Di Mizinke Oysgegebn.” “Lyrics and music composed by Mark (Mordechai) Warshavsky in Kiev, 1901.”

“That’s very helpful, but what about the dance?”

“I don’t know anything about a dance.”

Now that I had the correct spelling of the word, I proceeded to search a number of databases. I entered the word mizinke into the Bar Ilan University Responsa—Global Jewish Database, which contains commentaries, midrashim, hundreds of books of responsa and searchable text of 12,000 articles from various Torah periodicals and collections. This corpus represents more than 3,000 years of Jewish literary creativity.

“No results found.”

Admittedly, there is something about the broom sweeping and the donning of laurels that seems foreign to Jewish culture.

I then tried Otzar HaHochma, another well-respected digital library containing more than 62,000 Judaic books, scanned page after page in their original format. Again, “no results found.”

I decided to focus on Warshavsky and the song. Warshavsky was a famous Jewish folk singer and composer who was mentored by the great Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem. Together they were part of a circle of artists who frequented and performed in the cafes of Kiev. In addition to composing the words and lyrics to the mizinke song, Warshavsky also wrote the beautiful and familiar lullaby “Oyfn Pripetchik.”

The mizinke song’s theme is very traditional (see the lyrics in the sidebar to this article)—thanking God for the joyous occasion and ensuring that food is provided for the poor. But I still had no leads about the dance.

I contacted Zalman Alpert, reference librarian at Yeshiva University’s Mendel Gottesman Library of Hebraica/Judaica. Interestingly, Alpert told me he had recently researched the topic but didn’t come up with much. “There seemed to be a connection to Ukraine,” he said. “And so I inquired as to whether it was the practice among Skver Chassidut [that originated in a town called Skver in the Ukraine]. It was not.”

I had planned a trip to Israel and looked forward to continuing my investigation there.

The original edition of Warshavsky’s songs, including “Di Mizinke Oysgegebn,” published with the assistance of Sholem Aleichem in 1901. Warshavsky was a famous Jewish folk singer and composer.

Courtesy of YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

I asked my relatives in Tel Aviv, a couple of Polish descent, about the custom. (He was a Holocaust survivor from the city of Ruzhan.) Yes, they had both seen the dance at religious weddings in Israel. But she was indignant. “I find it repulsive . . . Can you imagine, a dance to symbolize the sweeping of the children out of the house? I welcome my children into my house with open arms.” The custom had not been practiced in Ruzhan, a vibrant town of Mitnagdim and Chassidim before the war.

Back in New York, I contacted a senior member of The National Yiddish Theatre—Folksbiene. I asked if the mizinke dance had appeared on the Yiddish screen or in theatre performances; perhaps this could explain its current popularity. “In all likelihood,” he said, “it did occur, as the chasuna [wedding] scene was a common theme and the newly arrived immigrants were seeking to connect and maintain a relationship with the culture they left behind in Eastern Europe. I don’t know offhand of any particular show [that featured the mizinke dance]. Identifying the specific production would be like finding a needle in a haystack. There is no index of the performances. You would have to start by going to the Library of Congress and sifting through all the event announcements and review them one by one.”

Back to square one.

Friends and acquaintances offered their own theories.

“It’s total naarishkeit [nonsense], a Hungarian custom,” said one acquaintance of Polish descent. “We don’t do it. You’re not Hungarian, are you?”

“It’s total naarishkeit, a Polish custom,” said another of Hungarian descent. “We don’t do it. You’re not Polish, are you?”

No progress. I figured I would try my luck at the New York Public Library, renowned for its expansive research services. Miryem-Khaye Seigel, librarian at the Dorot Jewish Division of the New York Public Library, informed me that the mizinke appears to predate the era of Jewish film and theater in the US. She also gave me a listing of Jewish dance experts I could contact.

I called the first name on the list, Judith Brin Ingber, a Jewish dance historian, writer, performer and educator residing in Minneapolis, Minnesota. We spoke and her colleague Helen Winkler from Toronto, Canada, the second name on the list, soon joined our discussions as well.

Both women committed substantial time and effort to helping me; they introduced me to a new world of Yiddishists, dance historians, folklorists, ethnomusicologists and Klezmer musicians. But when the smoke settled, Winkler’s statement summed it up: “Dr. Itzik Gottesman, [a folklorist and associate editor of the Yiddish Daily Forward], mentioned that in all of his readings in Yiddish, in European sources, he has never encountered either the mizinke dance or the krensl (crowning) ceremony. Itzik is very knowledgeable, so I thought he would have encountered it somewhere in his experience if it were widely known.”

Ingber noted that she and Winkler “both get asked about the mizinke dance more than other dance forms . . . the dance is a wonderful and powerful way to honor parents who are marrying off their last child. However it is done, whether with women sweeping around the mother-of-the-bride or with the parents seated in the center of a circle, it’s a heartfelt and important addition to wedding receptions.”

Unsuccessful, but still determined to uncover more about the mizinke, I turned to the National Library of Israel at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. My inquiry was directed to a professor of dance history, from whom I received a familiar response: “We have done a very extensive search of material available to us and have not found the source for the custom.”

Still, I did notice that the Ukraine was coming up over and over again. If all roads lead to the Ukraine, let’s take them!

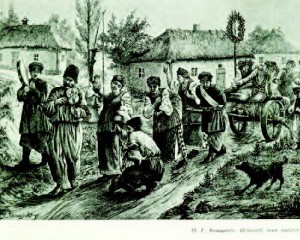

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Ukrainian wedding celebrations would extend for a number of days and on the last day of the celebration, it was the custom that parents be wheeled on a wagon to the local inn where they would frolic with their friends and family. “Woodcut from a painting,” by Heorhii Bilashchenko, dated 1889, shows the parents being wheeled around the village wearing wreaths on the last day of the wedding celebration.

Courtesy of the Ukrainian Museum and Library of Stamford, Connecticut/Lubow Wolynetz, curator and librarian

Turning back to local resources, I called the Ukrainian Museum in New York and was put in touch with Lubow Wolynetz, curator of the museum’s folk art collection. She was just completing the finishing touches on an exhibit entitled Ukrainian Wedding Textiles and Traditions. I felt I had finally come to the right address.

Wolynetz told me that during the second half of the nineteenth century, Ukrainian wedding celebrations would extend for a number of days; on the last day of the celebration, it was the custom that parents be wheeled on a wagon to the local inn where they would treat their friends and family and frolic with them. But nothing special regarding the youngest child, brooms or laurels.

I was disappointed. I had expected a major breakthrough.

But a theory was slowly beginning to form in my mind.

Based upon the information I had culled, I felt it reasonable to deduce that the mizinke had become a staple at weddings due to one reason: bandleaders.

YIVO’s Mloteck had intimated as much when she said that the famous bandleader and Klezmer musician Abe Schwartz had popularized the song in the 1920s. In fact, composer and musician Hankus Netsky, the founder and director of the Klezmer Conservatory Band and chair of the Contemporary Improvisation Department at the New England Conservatory of Music, identifies bandleaders as the source for the custom in his 2004 doctoral dissertation on ethnomusicology.

Wishing to leave no stone unturned, I e-mailed Dr. Ruth R. Wisse, professor of Yiddish literature at Harvard, for her theory on the matter. Within twenty-four hours, I received a response: “The spread of the mizinke krensl custom in America is due to the bands that perform at weddings. They organize [the mizinke] as part of their routines—without necessarily consulting the families (and occasionally to their great surprise).”2 Independently, Winkler arrived at the same conclusion.

And then I received this e-mail from Wolynetz:

When the [Ukrainian] wedding celebrations were coming to the end (after a few days), wedding guests would put the parents of the bride or groom on a wagon and take them to the village inn (bar) for the so-called “selling of the parents,” which meant the parents had to buy everyone a drink. If the parents married off their last child (son or daughter) then the guests would make wreaths and place them on the heads of the parents and thus take them to the village inn. In this frolicking way the wedding celebrations would come to the end.

She found the information in a Ukrainian magazine published in 1889, which included an engraving illustrating the event. The magazine article was based on the works of a Ukrainian ethnographer, folklorist and scholar, Pavlo Chubynsky (1839-1884), who traveled through Ukrainian villages in the second half of the nineteenth century, collecting folklore information, which he later published.

In the 1800s, many village inns and taverns in the Ukraine were owned or operated by Jewish families, she noted. Therefore, every time the parents of the newlyweds came into the taverns wearing wreaths and treated everyone to a drink, the Jewish tavern owners saw this. It is very likely that this is how the custom came to be part of the Jewish wedding.

A musmach of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, Rabbi Reuven G. Becker enjoys research, teaching and writing. If you would like to reach the author, please contact ja@ou.org.

Listen to Rabbi Reuven Becker discuss the history of the mizinke dance at www.ou.org/life/arts-media/savitsky-becker/.

Notes

1. Hankus Netsky states that “The crowning of the bride— unknown to Lithuanian Jews, Lubavitch Chassidim—is also observed by Ukrainian Christians” (Mark Slobin, American Klezmer: Its Roots and Offshoots [Oakland, CA, 2001] p. 71, n. 35).

2. It has been suggested that the custom of the broom is “based on a Cajun tradition for older unmarried brothers and sisters of the bride or groom to dance with a broom at the wedding reception, thus mocking their single status.”

This observation supports the notion that bandleaders were indeed promoters of the custom. New Orleans, a center of Cajun culture, is also known as a hub of musical talent. It is reasonable conjecture that bandleaders and musicians from the region performed the mizinke at Jewish weddings. Upon learning the theme, they naturally added the broom to the repertoire, expecting that it belonged with the dance. The wedding party, not knowing differently, accepted the direction from the musicians and found it to be fun and entertaining.

Lyrics of “Di Mizinke Oysgegebn”

Klezmer, hit the drums

Who will cherish me now?

Oy, oy, oy, God is great!

He has, of course, blessed my house

I’m giving my youngest daughter away

I’m marrying off my youngest daughter.

Stronger! Joyous!

You the queen and I the king.

Oy, oy, oy, I alone

Have with my own eyes seen

How God has made me prosperous

I’m marrying off my youngest daughter.

Stronger! Better!

Make the circle bigger,

God has brought me good fortune and joy.

Rejoice, children, all night long

I’m marrying off my youngest daughter.

Dear Uncle Yosi and good Auntie Sosi,

Sent me, for the groom’s meal,

Expensive wine without end

From the land of Israel,

I’m marrying off my youngest daughter.

Motl! Shimen! The poor folks have arrived.

Set the nicest table for them

Fine wine and fine fish,

Oy vey, daughter, give me a kiss!

I’m marrying off my youngest daughter.

Ayzik! Mazik! Grandma is dancing a kozatzki,

Don’t provoke the evil eye—but have a look

How she taps, how she steps,

Oy, such a simchah, such joy,

I’m marrying off my youngest daughter.

Itzik, you rascal! Why is your bow silent?

Shout at the musicians,

Are they playing or are they sleeping?

Tear the strings in two,

I’m marrying off my youngest daughter.

Translation courtesy of Lorin Sklamberg, sound archivist, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.