Rekindling the Flame: Neo-Chassidus Brings the Inner Light of Torah to Modern Orthodoxy

By Barbara Bensoussan

Editor’s Note: This magazine’s policy has always been to use Sephardic pronunciation, unless an author is known to use Ashkenazic pronunciation. Because in the neo-Chassidic movement Chassidus is referred to as Chassidus, not Chassidut, we felt it was important to spell the word as the movement does. Additionally, please note that many of those interviewed for this article use Ashkenazic pronunciation.

A prince once lay dying, and seeing that the doctors could do no more for him, the frantic king sent for a tzaddik known to be a master of medicine. The tzaddik told the king, “There is one cure that might help him. There is a rare precious gem that, if crushed and mixed into a potion, might cure your son. The gem can be found on a faraway island, but there is also one in the center of your crown.”

“What good does my kingship serve me if my only child dies?” cried the king. “Take the gem from my crown and cure him!”

This mashal (parable), which comes from the Ba’al HaTanya, the first Lubavitch Rebbe, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, was offered in response to those who opposed teaching the peninim of Torah in the open. The dying prince represents Am Yisrael, languishing from lack of inspiration; the gem represents the inner light of Torah that can revive him.

“From the middle of the eighteenth century, gedolim like the Ramchal [Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzatto] and the Ba’al Shem Tov began bringing forth the deeper secrets of the Torah,” says Rabbi Moshe Weinberger, mashpia at Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS) and the rav of Congregation Aish Kodesh in Woodmere, New York. “Halachah constitutes the physical life of the Jew, but the soul of the Torah is the potion we need to infuse it with life. Hashem saw that the Jewish people were suffocating, so He sent the Besht [the Ba’al Shem Tov] to revive them and give them a taste of the light of Mashiach.”

Despite the fact that the Orthodox world brims with minyan factories, glatt kosher vacation packages, yeshivot and kollelim and a thriving print media, Rabbi Weinberger is concerned. One thing is missing, he says: “the soul.” As he wrote in an essay that appeared in the online journal Klal Perspectives in 2012, “Our communities—spanning the entire spectrum of Orthodoxy—are swarming with Jews of all ages and backgrounds who have little, if any, connection to Hakadosh Baruch Hu.” Many of the off-the-derech youth, he says, are not running away from authentic Yiddishkeit; they simply “never met it.”

“There are many out there who may have been shown or taught a version of Yiddishkeit that is dry, that is cold,” agrees Josh Weinberg, a YU musmach who considers himself a neo-Chassid, and is one of many who look to Rabbi Weinberger for inspiration. “They may practice Judaism in their communities [due to societal pressure], but inside, there’s a lot of apathy and [it’s done by] rote. Chances are they were never exposed to this deeper and joyous side of religious observance,” says Josh, who lives in Riverdale, New York, and works as a photographer and videographer for NCSY.

Rabbi Weinberger’s outspoken encouragement of a deeper engagement with what he calls “the inner light of Torah” has caused others to describe him as the captain of a growing trend among the Modern Orthodox to reconnect with the spiritual vision of the Ba’al Shem Tov and his disciples and others who delved into this dimension of Torah. Some of the more popular Chassidic texts that appeal to this group include Rabbi Elimelech of Lizhensk’s Noam Elimelech, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev’s Kedushat Levi, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov’s Likutei Moharan, the seforim of Chabad Chassidus, including the Tanya, the seforim of Rav Tzadok HaKohen of Lublin and those of the rebbes of Ger—the Chiddushei HaRim (Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Rothenberg Alter), the Sefat Emet (Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter) and the Imrei Emet (Rabbi Avraham Mordechai Alter), as well as the writings of Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner and Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaCohen Kook.

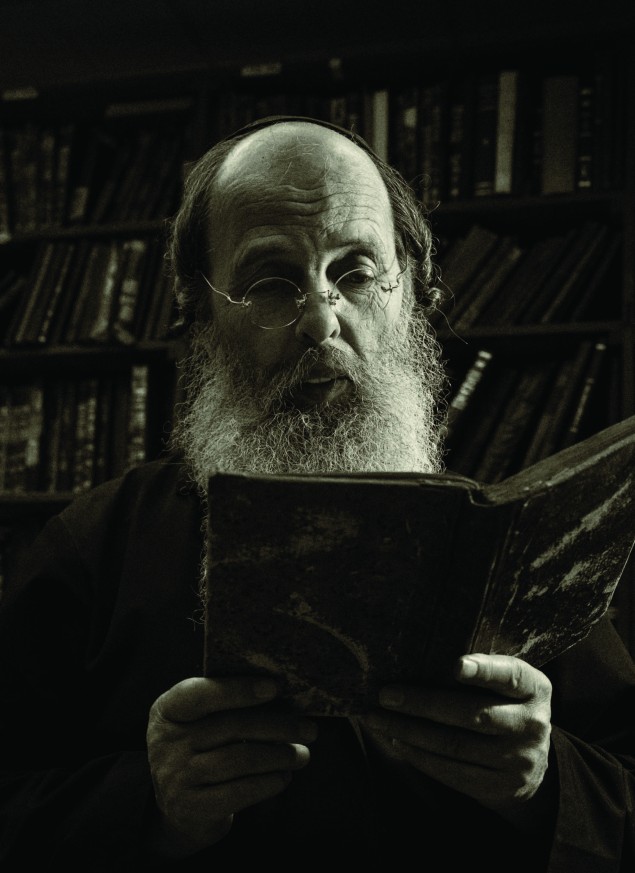

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger’s appointment as mashpia at YU indicates just how deeply the neo-Chassidus movement has impacted the Modern Orthodox world. Photo courtesy of Yeshiva University

Some adherents take on hitbodedut (meditation), attend tisches and farbrengen (Torah gatherings), immerse in the mikvah, engage in Carlebach-style davening and visit tzaddikim or kivrei tzaddikim (such as Rabbi Nachman of Breslov’s kever in Uman).

The Influence Spreads

Rabbi Weinberger’s appointment as mashpia at YU last year indicates just how deeply the neo-Chassidus movement has impacted the Modern Orthodox world. “I myself went to YU forty years ago,” Rabbi Weinberger says. “Today, it’s a different world. There’s still the same strong learning, but so many of the boys are thirsting for the life of inner Torah; in Eretz Yisrael, there’s a real sense of excitement in the hesder yeshivos, where the influence of Rav Kook is still felt.”

Rabbi Judah Mischel, a former rebbe at Yeshivat Reishit Yerushalayim and a popular teacher of Chassidus in Israel, maintains that the rediscovery of Chassidic teachings in the Modern Orthodox world is “changing the face of the community.” YU traditionally embraced a more intellectual or Litvish approach to Torah study. Now YU offers weekly shiurim in Chassidic thought, monthly farbrengen with Rabbi Weinberger as well as a Rosh Chodesh musical minyan, all of which represent a dramatic shift for YU. Rebbeim at YU noted the popularity of neo-Chassidus in Eretz Yisrael, where 85 to 90 percent of YU students study before attending the university. “The administration said that if this moves many of our students, let’s give it a try,” stated Rabbi Yosef Blau, senior mashgiach ruchani at YU, in a February 2013 article in Commentator, the YU student newspaper.

Rabbi Mischel, a resident of Ramat Beit Shemesh, Israel, who is a current student of Chassidic master Rabbi Avraham Tzvi Kluger, defines neo-Chassidus as “people trying to live Yiddishkeit from the inside out, to live more deeply and fully . . . . People today are refusing to be put into boxes. God is One, and His truth can be refracted in many different ways.”

Rabbi Weinberger may be the movement’s senior spokesman, but most of the followers are young. “The majority of the people involved with neo-Chassidus are under thirty,” says Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin, an avid follower of the movement who lives in Teaneck, New Jersey. Rabbi Bashevkin, who currently serves as the director of education for NCSY, earned semichah from YU where he completed a master’s degree in Polish Hassidut focusing on the thought of Rabbi Tzadok HaKohen of Lublin.

Noting the trend, some Modern Orthodox high schools have begun offering courses on Chassidus. Torah Academy of Bergen County in New Jersey offers an elective called “Introduction to Chassidut.” This past year, the Rae Kushner Yeshiva High School in Livingston, New Jersey, held a school-wide day-long program on Chassidus which stimulated so much interest in the subject the school decided to offer an ongoing course on Chassidic thought. The popular elective, open to eleventh and twelfth graders and called “Chassidic Thought on Ahavat Hashem,” focuses on studying works from some of the greatest Chassidic personalities, including the Ba’al Shem Tov, the Ba’al HaTanya, Sefat Emet, Kedushat HaLevi, the Piaseczna Rebbe (Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira) and others.

While Rabbi Eliezer Rubin, Rae Kushner Yeshiva High School head of school, does not see a mass movement of high schoolers becoming neo-Chassids, he does see a marked interest in Chassidic thought. He attributes this to the impact of the digital revolution. “Everything is individualized nowadays,” he says. “Even religion is individualized. We select our own music, our own games, our own TV shows through Netflix.” Now, he says, you can select your own style of Judaism.

Nor is this surge of interest in Chassidus limited to Modern Orthodox Jews in the New York tri-state area. Rabbi Shlomo Einhorn, dean of Yeshiva Yavneh in Los Angeles, says that every few months, a few shuls in the Pico-Robertson neighborhood, a solidly Modern Orthodox part of town, coordinate a tisch. Similarly, classes on Chassidic thought are sprouting all over, such as a class on the Tanya and Netivot Shalom, the work of the Slonimer Rebbe, offered in the Boca Raton Synagogue.

An All-Encompassing Approach

Joey Rosenfeld, a twenty-six-year-old enthusiast who used to give shiurim in Chassidus in New York (he recently moved to St. Louis), says that many of his friends found spiritual support in Chassidus when they returned from a year or two of learning in Israel and transitioned back into American life. “They come back after a year of inspiration and increased piety, which was easy to maintain in the bubble of the beit midrash, and find themselves among an affluent, modern lifestyle,” he says. “It creates cognitive dissonance: Either you go back to your old lifestyle, or you find new ways to cling to authentic Judaism. Chassidus offers an all-encompassing approach to Jewish life. It includes not only life in the beit midrash, but prayer, dealing with struggles and failures and connecting to God even through mundane activities.”

Rosenfeld adds that Chassidus also offers an alternative to the Litvish yeshivah tradition which emphasizes intense learning above all else. “Chassidus encourages people to connect to God in their own unique ways, in ways that make them feel good,” he says. “It’s less elitist. People don’t have to feel guilty about learning bekiut instead of b’iyun, or Tanach instead of Talmud or for picking up a sefer [with an English translation].”

Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Weinberg, who teaches and serves as mashgiach ruchani at YU’s Irving I. Stone Beit Midrash program (SBMP), agrees that the Chassidic approach promotes a balance sometimes missing in the yeshivah world. “For most people, it’s not realistic to hear that their only acceptable outlet is sitting in a beit midrash,” he says. “It’s liberating for them to find other means of connecting to Hashem that are authentic and not bedieved. The Litvish and the mussar approaches emphasize yirah and [the] Shulchan Aruch, but that can be [damaging]. The Chassidic approach is softer, more positive. It emphasizes simchah—simchah shel mitzvos, simchah shel chaim. It’s a different vision of what it means to be an ideal Jew.”

Rabbi Weinberg came to Chassidus through his brother Josh, mentioned earlier in this article, who studied in Israel about a decade ago under Rabbi Mischel. Through Rabbi Mischel, Josh and another brother became exposed to Chassidic ideas; upon their return, they passed along their enthusiasm to their oldest brother, Moshe Tzvi. “Chassidus has an energy I haven’t seen elsewhere,” Rabbi Weinberg says. “I had no connection to Chassidism as a child in Philadelphia beyond an image of peyos and shtreimels; I had no idea it could be a language of spirituality, of communication with Hashem.”

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger says that even those raised in Chassidic homes are coming to his shiurim, seeking to reconnect. “For some of them, Chassidus became a way of life, not a fire. Now they’re seeking a new spirit of Chassidism, a rekindling of the fire of the Besht. There are quite a few old-school Chassidim who regularly attend my shiurim.”

Roots of a Revival

Some credit Reb Shlomo Carlebach as being the first to bring Chassidic-style song and tefillah to the Modern Orthodox world; the first Carlebach minyanim introduced a certain Chassidic spirit and warmth into tefillah. “Many shuls had been having trouble getting a minyan when Carlebach started out,” says Dr. Chaim Waxman, professor emeritus of sociology and Jewish studies at Rutgers University. “His style of davening attracted a lot of people.” Today, neo-Chassidic musicians such as brothers Eitan and Shlomo Katz follow in the Carlebach tradition by offering audiences folksy, often inspirational music and teachings. At YU’s neo-Chassidic Rosh Chodesh minyan, some of the participants bring instruments.

Providing sociological context to the neo-Chassidic trend, Dr. Waxman notes that many hesder/Dati Leumi yeshivot in Eretz Yisrael emphasize Chassidic thought, particularly the teachings of Rav Kook, and American students who study there bring home these ideas. American culture, he says, is particularly receptive to them. “American Jews are brought up around the particularly American idea that religion is something that should be meaningful,” he says. “Spiritual seeking is something that has always been a part of the broader American culture. In the past couple of decades, there has been an increased emphasis on the question, ‘What does religion do for me?’”

Dr. Waxman says that Lubavitch Chassidism, which he claims is the fastest-growing movement within American Judaism, resonates particularly well among the Modern Orthodox because it has traditionally encouraged participation in the wider world, the pursuit of higher education, and reaching out to less-affiliated Jews. “Today, you have well-regarded intellectuals like Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz and Rabbi Joseph Telushkin producing biographies of the Lubavitcher Rebbe,” he points out. In general, the Modern Orthodox as well as unaffiliated Jews are more likely to connect with more outward-focused Chassidic groups such as Lubavitch and Breslov than with more insular groups.

Some young people are aware that their own family trees include Chassidic branches, which generates curiosity about Chassidism that leads to involvement. Those who were inspired by Chassidus in Israel may take on external signs like peyot or a gartel when they return home as a means of distinguishing themselves, as a way of marking the spiritual transformation they felt while in Israel. “The people involved [in neo-Chassidus] are a little unconventional, in the sense that they grew up in the Modern Orthodox world, then come home with peyos and a beard,” says Josh. “The YU world of Rav Soloveitchik and Brisk is very intellectual, and by comparison we may seem hippie-ish; some parents see it as a rejection. But most aren’t rejecting anything. They’re seekers who are looking for a deeper connection.”

“People are moved by sports and movies,” explains Rabbi Einhorn. “They want to be moved emotionally by religion too.”

Thus, it should come as no surprise that women also find neo-Chassidus appealing. One indication of this is the rise in women-only trips to Uman, led by female teachers such as Rebbetzin Yehudis Golshevsky of Jerusalem. These trips do not take place during the intense High Holiday season, when thousands of men flock to Uman; instead, the women tend to go on Rosh Chodesh, seen as a women’s holiday, and especially on Rosh Chodesh Kislev, which has significance for women since the ancient heroine Yehudis helped bring about the Chanukah miracle.

Rebbetzin Golshevsky, herself a product of a Modern Orthodox home who considers herself Breslov today, has been teaching Chassidic Torah for nearly twenty years in Israel. Her popular classes attract women from across the religious spectrum. Why do they come? “Oxygen,” she says. “The Jewish world is in serious need of oxygen . . . . There is nothing sadder to me than Jews going through the motions of observance without feeling the passion. Chassidus instills in a lot of people that passion, that fire, for serving God. It’s not that you can’t have the fire without Chassidus, but it sure is harder.”

An Unofficial Movement

When did this trend first take root? Some date it back about five years ago, when a small group of YU students who recently returned from studying in yeshivot in Israel decided to set up a chaburah to study Chassidic texts during winter break in the basement of a home in Teaneck. Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Weinberg was among those who delivered the shiurim. “That group snowballed into a lot of what’s happening now,” he says. “It became known as The Stollel, which now runs a Twitter feed and maintains continuous learning. Today the minyan [in Teaneck], which meets for chagim and special occasions, attracts hundreds of people—we had to move it from a home to a shul.”

“It developed into a sort of underground movement,” says Josh. “Some have even taken to calling its followers ‘neo-Chassidic Warriors.’”

Many of the off-the-derech youth, he says, are not running away from authentic Yiddishkeit; they simply “never met it.”

But the neo-Chassids from non-Chassidic backgrounds aren’t for the most part moving to Williamsburg or taking on the full Chassidic garb or minhagim. “Neo-Chassidus is turning back the clock 250 years on Chassidism,” Rabbi Bashevkin says. “That was before Chassidic minhagim even existed!” Some neo-Chassids dabble in Chassidic thought and practices, while others engage deeply with them.

“Neo-Chassidus is more about a consciousness, not a style of dress,” says Yitzchak, who maintains a blog for the movement and prefers to be identified by his first name only. “The social [aspect] is also an important part of the avodas Hashem—the cohesion of people sitting around a table together at a farbrengen, traveling together to Uman.”

According to Rabbi Bashevkin, there’s also a lighthearted side in the movement determined to put the geshmack [enthusiasm] back into Jewish practice. “There’s a sweetness and a rich sense of humor in the movement, a component which goes back to Rabbi Nachman of Breslov,” he says. “You have The Stollel’s Twitter feed, and another called #UofPurim—Purim happens to be a holiday that resonates well with this movement.”

Josh notes that this exuberance has a broad appeal. “A Jew is looking to be connected and the soul needs to be filled with something,” he says. “In a world where there’s so much excitement in nonkosher venues, the movement gives one the ability to fill the soul with holy things, giving young people an exciting way to connect to Judaism.”

Proceed with Caution

Not everyone is wholly enamored of neo-Chassidus. Rabbi Blau admits that the singing and dancing aspect of neo-Chassidus serves a need for people looking for ways to connect to Judaism in an immediate and emotional way, and allows young men not cut out for intensive study to find alternative outlets. But he worries that all this feel-good activity may be too easy a substitute for rigorous Torah study, especially among a generation with a low tolerance for delayed gratification. “I represent, to a degree, a more rationalist tradition,” he says. “When I was in yeshivah, the ‘best’ students were those who were either the smartest or most willing to persist for long hours in the beit midrash. How do you judge a ‘top’ student of neo-Chassidus? It’s impossible to know at this point if this trend will produce talmidei chachamim.”

Not everyone is wholly enamored of neo-Chassidus. Rabbi Blau admits that the singing and dancing aspect of neo-Chassidus serves a need for people looking for ways to connect to Judaism in an immediate and emotional way, and allows young men not cut out for intensive study to find alternative outlets. But he worries that all this feel-good activity may be too easy a substitute for rigorous Torah study, especially among a generation with a low tolerance for delayed gratification. “I represent, to a degree, a more rationalist tradition,” he says. “When I was in yeshivah, the ‘best’ students were those who were either the smartest or most willing to persist for long hours in the beit midrash. How do you judge a ‘top’ student of neo-Chassidus? It’s impossible to know at this point if this trend will produce talmidei chachamim.”

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger has his own concerns; he cautions against leaping into the fire of inner Torah without taking certain precautions. “If people jump in too quickly, without proper teachers, it can lead to imbalance and confusion,” he says. “There are many broken people out there looking for a fix. This is a less expensive high than drugs, but if it’s not grounded in halachah and connected to a living master, it won’t succeed.” Without guidance, the mix of youthful high energy and Chassidic practice can be volatile.

“Young people are still finding themselves,” says Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Weinberg. “If there’s nothing grounding [Chassidic practice], it can degenerate into trendy, even silly New Age-style practices.” Activities such as going to Uman or meditation shouldn’t replace traditional learning, but rather add a deeper dimension to it. Rabbi Weinberg illustrates this idea with an image taken from a Chassidic sefer, which describes a father dancing at a wedding with his young son on his shoulders. The fact that the father has an obligation to be careful about his precious cargo doesn’t detract at all from the joy of his dance.

Rosenfeld similarly believes that it’s easy for some to pervert Chassidic concepts of joy, prayer and tikkun olam to the detriment of halachic observance. “As much as it’s a problem to be a vessel with no light, you can’t be light with no vessel,” he cautions. Another adherent, Yitzchak, adds that it’s simplistic to view Chassidic practice as all about prayer and kabbalah, and not about serious learning. “Parts of the Zohar are very dry and technical!” he points out. “Tanya is very complicated—it requires tremendous zitzfleisch [patience]. While on the one hand you have these Chassidic stories about people sitting and reciting the Aleph Bet to show that it’s possible to connect to Hashem on a simple level, the intellectual tradition of Chassidus is very deep and sophisticated.” He adds that it can be just as challenging to be matzliach (successful) in prayer as it is to succeed in learning.

Many of the movement’s adherents mention that Chassidic writings predict that in the days before Mashiach there will be an explosion of meaning in the Jewish world. “Rav Kook, who came from one Chabad and one Litvish parent, wrote that at the end of days there will be a conversation between the followers of the Vilna Gaon and the followers of the Ba’al Shem Tov,” Rosenfeld says. “He said that the students of the Besht will herald the coming of Mashiach.”

Rabbi Mischel likewise tells a story that the Besht interacted with Mashiach in the upper chambers of Shamayim (Heaven), and was told that Mashiach will come when the wellsprings of inner Torah spread to the outside. “Rav Kook wrote that ours would be a ‘wondrous generation,’ in which many things will begin happening all at once,” he says. “Ours is a postmodern reality in which there are many options, and many spiritual options.”

Until Mashiach comes, we can look to this generation’s revival of Chassidus as a way to comfort and warm the Jewish soul in the trying times before his arrival. Rabbi Weinberger relates that a Mitnaged once challenged the Chassidic master, the Tzemach Tzedek (Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn, the third Lubavitcher Rebbe): “What’s the difference between you and me? We study the same Torah and observe the same mitzvos.”

“It’s like two chicken soups,” the Tzemach Tzedek replied. “The ingredients are exactly the same. But one is cold—and one is hot.”

Barbara Bensoussan, M.A., is a contributing editor of Mishpacha magazine and writes for Jewish Action and other media outlets. She is the author of the young adult novel A New Song (New York, 2006) and the cooking memoir The Well-Spiced Life (Lakewood, NJ, 2014), has worked as a university instructor and social worker, and currently writes for Jewish newspapers and magazines.

On Chassidus

Excerpted from Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, Faces and Facets (Brooklyn, 1993), 141.

In the darkest days of Jewish history, Chassidism brought a new hope, a new happiness to millions of people. It brought Judaism to life again, making it meaningful to the masses. The radiance that illuminated two centuries of Jewry may yet have another great purpose to serve.

I was once at a conference where it was discussed what kind of Judaism we will have in America 100 years from now. Some people said the trend would be toward Reform. Others said it would be toward the middle, conservative movements. The pessimists said that there would be no problem, given the current rise in intermarriage, for in 100 years, there would be no Judaism at all in America. But one person suggested that 100 years from now, Chassidic Judaism would dominate the American Jewish scene.

I would agree. The Chassidic spirit, the Chassidic philosophy, is certainly the up-and-coming thing. Perhaps this is our answer, the missing ingredient which will provide our coming generation with a new kind of Judaism, a turned-on Judaism . . . Maybe we have to get involved in this love affair of the Chassidim, this love affair with God.