Reflections on 9/11

One Short Decade

Rabbi Benjamin Blech

“The great tragedy of life,” Kierkegaard wrote, “is that it must be lived forward and can only be understood backwards.”

We cannot truly understand events as they unfold. It is only with the perspective of time that we can begin to grasp their true meaning. It is a truth that rabbinic commentators point out is expressed in the Torah.

In response to the request from Moses that he be allowed to see God’s glory, the Almighty tells him, “You can see My back, but My face you cannot perceive.” The Almighty obviously has no physical form; what He meant was that His relationship to the world could only be understood in retrospect.

A decade has passed since the horrifying attack of 9/11 on American shores. Life has never been the same since then, neither here nor in the rest of the world. And what new insights have we gained since that tragic moment in September of 2001?

In one sense, we share the feeling of Zhou Enlai, the first premier of the People’s Republic of China, who when asked in the mid-twentieth century what he thought about the impact of the French Revolution of 1789, responded simply, “It is too soon to say.” We cannot yet fully grasp all the consequences of that seminal moment in history when Bin Laden chose to begin the war of East versus West, of Muslim fanaticism against Judeo-Christian values.

But what we have learned in these last ten years is that we are engaged in a conflict rooted not in a desire for more land, for more wealth, for more power, but a war that is meant to decide between two visions. “The difference between you and us,” Osama Bin Laden famously said, “is that you glorify life and we glorify death.” There cannot be a starker and more succinct summary of what is at stake in this battle. To call our enemies terrorists is to diminish the scope of their evil intentions.

Today at the very least, we recognize that what we are fighting for is nothing less than the survival of civilization. And our goal must therefore be the Biblical mandate we have been given from God in the Torah to “choose life.”

Rabbi Benjamin Blech, the author of many highly acclaimed books, is a professor of Talmud at Yeshiva University and the rabbi emeritus of the Young Israel of Oceanside.

Faith in Uncertain Times

Dr. Erica Brown

In the years since 9/11, the world has witnessed travesty of both a natural and a human order that seems unparalleled. My ten-year-old daughter has grown up in a world that has experienced more global havoc than in all my years cumulatively. Some years ago I came across an article in the New York Times where a father pondered the fact that as a child, when he was sent off to school in the morning his father said, “Have fun.”

He says, “Be safe.”

The post-9/11 universe we live in is a different world than the relatively innocent world of our own childhoods. The ground swell of calamity has shifted the way that we look at disaster, at terrorism and even at ourselves. Wars in the old days were about sides, geographic spaces, and a map of possible outcomes. The role of civilians was relatively clear. Today everything feels much murkier. We walk in an emotional swamp with a level of immense insecurity that we neither understand nor control.

As religious beings, we have to learn to reside in a universe that defies comprehension.

If you look at the Book of Job, you find that Job’s world had this sort of quality. There was a profound mystery to all the suffering that Job’s so-called friends tried to dissipate by attributing blame and cause. Zophar, one of Job’s three friends in the book, says to Job that although God’s world is unfathomable, Job should look inside and correct his behavior and he will therefore stem his losses: “If there is iniquity in you, remove it, and do not let injustice reside in your tent–then, free of blemish, you will hold your head high. And, when in straits, be unafraid. You will then put misery out of your mind . . . ” (Job 11:14-16).

But Job gets the last word in this and other arguments: “My eye has seen all this; my ear has heard and understood it. What you know, I know also; I am not less than you. . . If you would only keep quiet it would be considered wisdom on your part. . . ” (13:1-2, 5). Job’s response is to tell his friends not to be so certain about the moral landscape and not to believe that they have the answers in a world that defies comprehension. Humility is the only honest response to mystery.

We’ve all heard the arguments of Job’s friends when it comes to the issue of theodicy, why bad things happen to good people. Often these arguments represent appropriate and desirable spiritual behavior. We read much of the same in Eichah, the Book of Lamentations: “Let us search and examine our ways and turn back to the Lord” (Lamentations 3:40). What is the difference? Why does Job get so indignant and angry when Zophar and the others call him to task for his suffering?

Job understands that we walk in a world much larger than ourselves that human reason will never comprehend. We can and should take accountability for our role in any disaster, both direct and indirect. We need to be introspective when any tragedy happens, as directed by Eichah. But ultimately, there is an acute difference between human goodness and the Divine master plan, to which we will never be privy. As religious beings, we have to learn to reside in a universe that defies comprehension. If we did not understand this before 9/11, we certainly understand it now, ten years and many calamities later. The kind of religious fundamentalism and certainty that underlies terrorism and so much of global politics today can only be fought with Job’s posture of sacred uncertainty.

Dr. Erica Brown is a writer and educator who serves as the scholar-in-residence for the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington and consults for the Jewish Agency and other Jewish non-profits. Her most recent book, In the Narrow Places: Daily Inspiration for the Three Weeks, was published by OU Press.

Haunted by 9/15

Rabbi Ilan Feldman

A non-observant woman from Marietta, Georgia drove thirty miles to my shul on Shabbos, September 15, 2001 to seek spiritual guidance in dealing with the trauma of the previous Tuesday. When she arrived, the doors of the main shul were closed while I delivered my sermon on the obvious topic. She was told she could not enter, so she left. No one took her name.

I have undertaken no surveys, and have seen no data, about shul attendance in the days and weeks following 9/11. But something tells me that this nameless and unaffiliated woman was extremely rare. She came to an established Orthodox house of worship seeking spiritual succor. Millions of American Jews evidently did not. What did they “know” about our shuls?

Where do unaffiliated, spiritually discomfited Jews go when they have questions, when they look for spiritual solace? Why did they not flood our shuls in those confusing and painful days?

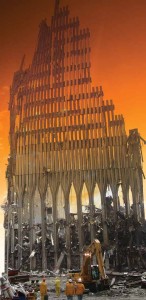

9/11 was so painful, sad, and tragic, and it happened on a scale that provoked wonder, and searching, and awe as well. It was Biblical in its dimensions. Nearly 3,000 of our countrymen perished in an instant–ground to death, burned alive, or fell to their deaths–in an inconceivable reduction to rubble of the most famous symbols of the West’s material success, while the entire planet watched on live, international television. Headquarters of the most powerful nation in the history of man were attacked without a single defensive shot fired; the city gates of an entire nation—its airports—were sealed in fear for days; White House staffers were forced to flee in panic from the symbol of leadership and stability.

Church attendance spiked considerably after 9/11. In the Orthodox Jewish community, in those spiritually concentrated days preceding Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, we can all recall a spiritual intensity rarely matched. There were special gatherings and speeches and Tehillim, and there was a sense that thousands of Jews were examining their lives, refreshing their commitments to loved ones, and rearranging priorities to reflect a more authentic Jewish approach to life. All this is eloquent testimony to an authentic and personal connection to God.

But it is 9/15 that still haunts me together with 9/11. I came to shul that Shabbos expecting to see some strange faces in shul–people were looking for answers. I was surprised to see no new faces that morning, and my surprise turned to sorrow when I realized how unprepared we were as a community when on a Shabbos following such harrowing tragedy, it did not occur to me, the rabbi, or to anyone in the lobby to make sure a strange face was welcomed and taken care of. Could this have happened that weekend in a church?

Where do unaffiliated, spiritually discomfited Jews go when they have questions, when they look for spiritual solace? Why did they not flood our shuls in those confusing and painful days? Had they come, would they have been welcomed? Would they have found our services to be islands of spiritual solace and inspiration, or would they have found the spiritual doors sealed, as mine were physically ten years ago?

As Jews, we don’t commemorate; rather, we take responsibility. We promised, long ago, to be reliable in seeing God everywhere, even in tragedy. We pledged to be that nation that never ceased to seek Him and see Him, even in the face of the most trying circumstances, and articulate His existence to the world.

Our shuls can—and should—be inviting spiritual centers designed to bring God’s chosen closer to our Chooser. For a Chosen People, tragedies remembered but not transformed into encounters with God, are wasted tragedies. It is not

too late to let 9/11 propel us to make sure 9/15 doesn’t happen again.

Rabbi Ilan Feldman has been the rabbi of Congregation Beth Jacob in Atlanta, Georgia since 1991.

A Mitzvah Remembered

Rabbi Ron Yitzchok Eisenman

I have no personal story to relate about 9/11. Thank God, neither my family nor I were near or affected directly by the tragedy. And although there are a number of families in my shul who were rescued from harm that day, no one was hurt. What, then, do I recall when I think about 9/11? What lesson is embedded in my conscious? The lesson that remains with me is from a woman whom I barely knew; today, ten years later, I cannot even recall her name.

For weeks and even months after the attack, people were recounting stories of those who “could have been there,” however, miraculously, because they performed a particular mitzvah or decided to stay longer in shul that day, they were saved from the tragedy.

One day a few months after 9/11, a woman who was visiting overheard a few of us discussing the terror attack. She walked over to me and said, “Rabbi, may I have minute of your time?” I was sure she was going to tell me another one of those near-miss stories that we were constantly hearing. Instead, she tearfully recounted the following:

I have just returned from a shivah home of a family that lost a father in the 9/11 attack. The man left a family of young children. At the shivah, one of the daughters, she could not have been more than twelve or thirteen, was sitting silently with her sisters and mother as everyone was gathered around them crying. Suddenly, the girl looked up and said, “Imma, I am happy for one thing. Remember the night before Abba went to work for the last time? Abba and you came home from a Bar Mitzvah and when you came into the house, Abba said, ‘I am really thirsty and hot. Could anyone please bring me a cold glass of water with ice in it?’ Although all of us were in the room, I looked at Abba and saw how hot he was, and I jumped up and brought him the water with the ice in it. He was happy that I brought it to him. He smiled and said ‘Thank you so much Malkie; that water was exactly what I needed right now!’ Imma, that was the last time I was able to do the mitzvah of kibbud av. I remember so clearly Abba’s face as he drank the water and how happy I felt that I was able to make him happy. I am happy that I have this as the last memory I will ever have of Abba.”

I dissolved into a river of tears after she finished the story.

I will never forget the story and think about it often, especially when I have to decide if I should spend more time with my children, my wife, or someone else whose company I cherish.

Rabbi Ron Yitzchok Eisenman is rabbi of Congregation Ahavas Israel in Passaic Park, New Jersey.

Patterns of Evil

Rabbi Marvin Hier

Ten years ago on September 11, my wife and I had just come off the plane at London’s Heathrow Airport, when we saw people everywhere glued to television monitors, motionless as if in a trance.

We didn’t realize then that our world had changed forever that morning. Who can ever forget the heart-wrenching stories of heroism of people like Shimmy Biegeleisen, who phoned his wife just seconds after the second jet hit the South Tower to tell her how much he loved her and when she handed the phone to his friend, he told his friend, “Take care of Miriam and take care of my children, I am not coming out of this.” He then recited the twenty-fourth Psalm over the phone to his wife and family. And when he finished the verse, “Who shall ascend on the mountain of the Lord? He that has clean hands and a pure heart,” he screamed into the phone, “Oh God!” and the line went dead.

But it is not only the victims who must never be forgotten. We must never forget their murderers, the religious leaders who inspired them, and the millions around the world who cheered them on and called their actions an act of martyrdom. Can you imagine the insanity that God would reward such infamy?

In a verse in the Book of Genesis when Jacob wrestles with the angel, Jacob suddenly turns to the angel and asks him, “Tell me, what is your name?” And the angel replies: “Why do you ask my name?” To which the Biblical commentator Rashi offers this explanation: “You want to know my name. Do you not know that evil has no fixed name? Our names always change in accordance with the times.”

In the 1930s, evil was a swastika. And the world did not know how to react. Today, evil is those who murder and maim as a means of pre-purchasing their tickets to Heaven. Only their garb and logo have changed.

Had the world listened to Winston Churchill in 1937, there may never have been an Auschwitz in 1942.

But we never get it, do we? It’s been ten years and we still don’t have a UN resolution forcing every nation to go on record condemning all acts of terrorism against any people. It’s been ten years, and there has been no UN resolution condemning suicide bombing as a crime against humanity.

But stay tuned—changes may be on the horizon. Osama Bin Laden is dead, and the Arab street is in the process of getting rid of its dictators. Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi and Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad are on the ropes. The Middle East’s Tower of Babel is about to come tumbling down with the introduction of “multiple languages,” which include the words “freedom” and “democracy,” words that have never been uttered in the Arab world.

But stay tuned—changes may be on the horizon. Osama Bin Laden is dead, and the Arab street is in the process of getting rid of its dictators. Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi and Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad are on the ropes. The Middle East’s Tower of Babel is about to come tumbling down with the introduction of “multiple languages,” which include the words “freedom” and “democracy,” words that have never been uttered in the Arab world.

To win this war, we must remember what Churchill said at Harvard in 1943, “We do not war primarily with races… tyranny is our foe, whatever trappings or disguise it wears–whatever language it speaks. . .we must forever be on our guard. . . ever vigilant, always ready to spring at its throat.”

Rabbi Marvin Hier is the founder and dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and its Museum of Tolerance.

9/11: A Shattering of the Idols

Rebbetzin Leah Kohn

As we try to absorb the magnitude of 9/11, the horrific event that forever changed the world’s perspective, we are struck by the realization of how acutely vulnerable we are. Prior to September 11, 2001, most of us felt that we lived in the safest place on earth. This illusion was shattered right before our eyes. It’s terrifying to think that in an instant, we can be reduced to mere ashes.

As Jews, we know, however, that that which we transform into eternity can never perish. Three thousand lives were lost, but they are not completely gone. All the good deeds these individuals accrued, the relationships they nurtured, and the bond they built with Hashem, these are their eternal investments, and these individuals are fully alive in the World to Come.

An event of this magnitude inevitably causes us to question our priorities and the direction of our lives; it causes us to evaluate where we want to invest our limited time and our energies. Of course, we need to live in this world and make a living. We need a home to live in and a car to drive. But what should our hearts, our souls, and our minds be preoccupied with? Can we really afford to squander our time here investing solely in materialistic pursuits?

Although we no longer have prophets, God communicates with us through the events that occur in our individual lives, to Klal Yisrael as a nation, and to all humanity. It’s obvious that there is a powerful message to be found in the life-altering day that has become known as 9/11. The Almighty is speaking to us.

What was attacked? The Pentagon and the Twin Towers, the epicenters of American ideology. We Americans saw all too clearly that neither military prowess nor financial success could shield us from harm.

It’s obvious that there is a powerful message to be found in the life-altering day that has become known as 9/11. The Almighty is speaking to us.

America had built one of the mightiest armies with the most sophisticated weaponry; nevertheless, it was rendered helpless against the raw evil of 9/11. What was the weapon of choice used by these terrorists? Knives. Primitive knives. We live in the technological age, yet such helplessness in the face of primitive weapons is common in Eretz Yisrael too, where often the IDF finds itself defenseless against Arab children throwing stones, suicide bombers, or smugglers using underground tunnels to sneak in weapons. What is the message in all of this? That nothing can guarantee safety. Hashem is telling us in no uncertain terms that it is the strength of our connection to Him, and that alone, that can keep us truly safe and secure.

The same holds true for America’s other primary preoccupation—money. In the aftermath of 9/11, the stock market plummeted. The two gods of America—power and money—lay shattered and broken in front of our eyes in a matter of minutes. We will never enjoy the confidence we once took for granted.

9/11 forced us to face the fact that we are living in galus, exile. What’s the nature of galus in America? On the one hand, it doesn’t seem like galus; there has been no other time in our history when we have enjoyed such freedom. We have whatever is necessary to live our lives as religious Jews. We feel totally at home in America. But there is an insidious side to this exile. To an extent, the American dream and its pursuit of comfort and pleasure has affected our lives as well. America’s ideology is that every behavior, no matter how deviant, is morally acceptable as long as it makes one happy. This message has subtly penetrated into our way of thinking. We have to ask ourselves: Is spirituality our focal point in life? Do we invest in the material more than we should? What do we really worship?

Part of the difficulty we have in defining ourselves and our life goals is due to the fact that we don’t appreciate who we are and what we have within us. The Prophet Hosea exhorted the Jewish people (14:2-4), “Shuva Yisrael ad Hashem Elokecha ki kashalta b’avonecha, Return Yisrael to Hashem, your God, for you have stumbled through your iniquity.” The most common interpretation of the pasuk is that the Jewish people have sinned and God is saying, “Come back to me, I’m ready to accept you.” According to a beautiful interpretation by the Sefas Emes, the Navi is calling on us to return to Hashem, “Elokecha” —the personal Hashem, the Godliness within ourselves. He is reminding us not to shortchange ourselves by identifying only as physical beings. Understand who you are, he pleads with the Jewish nation, understand that you have Godliness inside you, and then it’s much harder to commit a sin.

Teshuvah is usually understood as the process of mending one’s ways. However, teshuvah is more than just rectifying one’s behavior; it’s about deepening one’s relationship with Hashem. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, we were all jarred into rethinking the direction of our lives; unfortunately, as time passes, it is all too easy to slip back into our old patterns and become complacent. As the towers fell, we witnessed the shattering of illusionary gods. We have to make certain to internalize that message of 9/11, and invest more in what is eternal.

The enormous loss of life is painful beyond words. But as we continue to rebuild ourselves and our future, we have the one true God to hold on to. Only He can help us learn what we need to from this tragedy as we steer our lives in the right direction—the direction of immortality.

Adapted by Bayla Sheva Brenner, senior writer in the OU Communications and Marketing Department, from a lecture by Rebbetzin Leah Kohn, director of the Jewish Renaissance Center in Manhattan. The lecture was delivered at Congregation Torah Utfillah, in Brooklyn, New York, on September 25, 2001.

We Were Changed for the Better

Rabbi Allen Schwartz

What we have learned in these ten years? How have we changed? There is no question that our enemies continue to try to harm us. We recently heard of a plot by our enemies to grow beards and sidelocks so they can bomb unsuspecting worshippers. How can we not change in the face of such nefarious intent? The answer is that we must become better. And in the immediate aftermath of that day in 2001 that will live in infamy, we did. We started collections for 9/11 victims and their families. We donated blood for those who needed. We wrapped thousands of sandwiches for emergency workers. We led candlelight vigils. We led non-stop shemirah shifts for a year for bodies that were brought into the medical examiner’s office from Ground Zero. We made efforts to resolve every single potential agunah case that resulted from the attacks. And the broader New York community as well as the entire country lent each other a collective shoulder to rest weary heads in the face of the attacks. There is, in fact, no greater evidence of how we—New Yorkers—had changed following 9/11 than the Northeast blackout of 2003. Many New Yorkers remember the looting and outright lawlessness that accompanied the blackout in 1977. The rampant crime further devastated a dismal blight that had already descended upon the city. The power outage of 2003 was profoundly different. While it is true that the general landscape of the city had changed by then, the contrast is still profound. New Yorkers helped each other at every turn, and no looting took place. Thousands of young people assisted the elderly in coping with the scorching heat, and water bottles were left outdoors for all to take. There was an overall sense of camaraderie that prevailed throughout the city, and many people attributed that to the extraordinary sense of unity New Yorkers felt—and hopefully still feel—in the aftermath of 9/11. We were changed for the better.

Rabbi Allen Schwartz is rabbi of Congregation Ohab Zedek in Manhattan

Remember the Enemy

Rabbi Steven Pruzansky

The Jewish people are quite proficient in exercises of memory, and therefore we will never forget the horrific events of September 11, 2001–the mass murder of almost 3,000 human beings and the destruction of iconic American sites by Islamic-Arab terrorists. Like the Kennedy assassination for a different generation, few will ever forget where he or she was at the moment the Twin Towers collapsed under the overbearing weight of ferocious and sadistic evil. The fear for the fate of friends and loved ones, the dread felt by families of the missing, the devastation wrought to thousands of families, and the attacks on American symbols will never leave us. It was the first act of war on American soil since Pearl Harbor, but this assault had tens of millions of eyewitnesses.

For Jews, remembering is more than an exercise; it is a mitzvah found in several contexts and noted for its specificity. We are bidden to remember daily the Exodus from Egypt–both the event and its prelude and aftermath. Pious Jews also recall every day the Revelation at Sinai, the sins of Miriam and the Golden Calf, and Shabbat as well. And we are all mandated to “remember what Amalek did to you on the way when you left Egypt” (Devarim 25:17)–who they were, what they did, and what our response should be: eternal vigilance.

Note well the words of the verse: “Remember what Amalek did. . . ” –not simply what was done by a nameless, faceless enemy–but by Amalek. There is no reluctance to name the enemy. The modern but hollow demands of political correctness have required a concealment of the enemy’s identity. Notwithstanding ten years of war against radical Islam that has attacked a score of countries across the globe and murdered thousands more, Western man remains hesitant to recall the Arab terror of 9/11 by even calling it the Arab terror of 9/11. It is termed simply “9/11,” or the “tragedy,” or the “catastrophe” of the Twin Towers “imploding,” as one memorial states it. The moral imperative of not blaming all Muslim-Arabs for these crimes has disintegrated into not blaming any Muslim-Arabs, of whatever political stripe or passion, for these crimes. That is an offense to the memory of the victims, and to those who have led the battle against radical Islam for the past decade. We, too, have been guilty of these linguistic contortions that breed historical distortions. As Jews, we should know better.

Nevertheless, the Arab terror of 9/11 also engendered unprecedented acts of kindness, and a unity forged in a common struggle against evil. Many across the world who belittled, disparaged, or ignored terror against Jews in Israel now found terror coming to their homes, writ large. Americans, especially, saw Israel’s plight in a different light. But in the wake of this horrendous crime, we also witnessed and were inspired by acts of dedication and love that briefly enabled us to soar beyond the patterns that too often dominate our mundane lives and thoughts. Those too are indelible parts of our memory of America’s appalling encounter with radical Islam, for which freedom and true faith are the eternal antidotes.

Rabbi Steven Pruzansky is rabbi of Congregation Bnai Yeshurun in Teaneck, New Jersey.