Mesorah: The Rav Speaks

Due to the ongoing relevance of the topic of mesorah, Jewish Action is pleased to present two important perspectives on this critical issue.

Below is a synopsis by Rabbi Steven Weil of a brilliant and influential speech delivered in 1975 by Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik where he outlined the role of creativity and conservation in Torah. Following this is a profound essay by Rabbi Dr. Michael Rosensweig on the relationship between the Oral and Written Law and the challenges of “halachically navigating the ambiguities of modern life.”

Below is a synopsis by Rabbi Steven Weil of a brilliant and influential speech delivered in 1975 by Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik where he outlined the role of creativity and conservation in Torah. Following this is a profound essay by Rabbi Dr. Michael Rosensweig on the relationship between the Oral and Written Law and the challenges of “halachically navigating the ambiguities of modern life.”

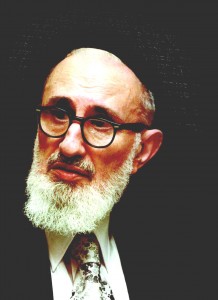

More than three decades ago, in response to a controversial proposal to annul troubled marriages, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik explained at length its problematic aspects in a lecture to Yeshiva University rabbinical alumni. The Rav’s powerful description of mesorah, of the tradition that undergirds our religious framework, remains instructive to this day and deserves review.

Torah Study As Revelation

Torah study, the Rav tells us, entails more than just learning sacred material. It is not merely a dry intellectual experience but is a religious experience, a recreation of the Sinai Revelation, a reaching out to God through His word. It is, the Rav said, “a total, all-encompassing and all-embracing involvement, . . . an ecstatic experience in which one meets God.” The Rav described how, when he would sit down and open a Gemara, he felt as if someone were sitting beside him looking over his shoulder. This wondrous experience is the presence of the Almighty who never deserted the Torah and accompanies it whenever someone studies it.

Torah study is an “ecstatic, metaphysical performance”; it is a personal revelation. We therefore must approach learning Torah the way our ancestors approached the receipt of the Torah at Mount Sinai—with fear, awe, tremor and trembling (see Berachot 22a). Torah study must include deep humility, a recognition that one is standing before the Almighty, which itself leads to surrender to the Torah’s, meaning God’s, demands. If a Jew is impure and incapable of experiencing the presence of the Almighty, he is forbidden to study Torah because he lacks this crucial attitude.

Why do we consistently refer to the act of accepting God’s sovereignty as “kabbalat ol malchut Shamayim, accepting the yoke of God’s kingship”? Of what significance is this yoke, this harness reining us in? The Rav explained that submission to God can be uncomfortable, even a burden. People instinctively struggle for freedom, for complete independence of thought and action. Judaism, however, rejects this, demanding that its adherents exercise control over their natural desire for autonomy. We must surrender to Torah rather than allowing our limited intellects to depart from it or our fanciful imaginations to distort it. This surrender is two-fold: we must forfeit our everyday logic and our everyday will.

The Almighty summons us to live halachically, and we have no other choice. This is Torah; this is surrender; this is kabbalat ol malchut Shamayim.

Torah’s Internal Logic

Torah study requires an absolute commitment to seeking truth and only truth. However, that truth-seeking must be in its proper context. Every discipline has an internal logic and halachah must be studied only through its own lens. One cannot apply what the Rav called “mercantile logic,” the everyday reasoning of a businessman, to the paths of Torah. Rather, one must use singular halachic Torah thinking and understanding. “The truth,” the Rav said, “is attained from within, in accord with the methodology given to Moses and passed on from generation to generation.”

One must become a part of the conversation of the ages, interacting with the classical commentators on their own terms and continuing this ongoing study within the halachic framework. Mixing in other intellectual disciplines—for example, historicizing or psychologizing debates—is an act of distortion, an insertion of a foreign construct into the native Torah environment, that undermines Torah’s very foundations.

It is ridiculous, the Rav averred, to say that one has discovered something that the Rashba, Ketzot or Vilna Gaon did not know. One must join the ranks of chachmei hamesorah, the sages of our tradition, and not try to rationalize the sacred based on secular concepts. Just like one cannot change a mathematical postulate with an interesting psychological interpretation, neither can one alter halachah through other disciplines. Such a non-halachic approach is actually anti-halachic; it inevitably and tragically leads to assimilationism and nihilism as the sacred is rendered mundane and malleable.

Confidence in Torah

We must also surrender our everyday will, the desire to survive and succeed, and instead embrace the Divine will. We cannot yield to social or scholarly critiques regardless of the apparent price. We must not only stand strong physically, refusing to act against the Torah in any way no matter how unpopular that insistence may be, but we must also resist emotionally. We dare not feel any inferiority due to our principled stance. Halachah stands on its own, and we are neither intellectually nor morally negligent for refusing to cooperate with modern intellectual trends that undermine it.

We stand proud of our mesorah, without apology or compromise. In the Rav’s opinion, Judaism “does not have to apologize either to the modern woman or to the modern representatives of religious subjectivism.” Despite the pressure we may feel, we cannot event attempt to nudge halachic norms toward what the Rav calls “the transient ways of a neurotic society.” We must recognize the fleeting nature of modern political and ideological trends as compared to the eternality of the Torah.

We must recognize the fleeting nature of modern political and ideological trends as compared to the eternality of the Torah.

The Sages of the Tradition

When the Rambam (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Teshuvah 3:8) describes a denier of the Torah, a heretic who rejects a fundamental principle of Judaism, he includes not only one who denies the Oral Torah but also “hamachish magidehah, one who rejects its transmitters.” This startling phrase is a powerful expression of the nature of the Torah Shebe’al Peh, the Oral Torah. The sages throughout the ages serve as God’s conduits for transmitting the Torah.

These great scholars, the living Torah scrolls, the chachmei hamesorah, stand for more than their own physical existence. They are links in the chain of Torah, participants in the ongoing dialogue that began at Sinai. Whoever criticizes them, whoever finds fault in their character or personality, their behavior or conduct, whoever suggests that they are biased or untruthful, rejects not only them but the Torah they transmit. The Rav clearly stated, “Even those who admit the truthfulness of the Torah Shebe’al Peh but who are critical of chachmei Chazal as personalities, who find fault with chachmei Chazal, fault in their character, their behavior, or their conduct, who say that chachmei Chazal were prejudiced, which actually has no impact upon the Halacha; nevertheless, he is to be considered as a kofer [denier].” The chachmei hamesorah, the greatest talmidei chachamim of all times whose personalities and outlooks were formed by the sacred texts they wholly embraced, represent Torah and one who rejects them denies all.

Halachic Continuity

The Rav discussed the proposal of the time—to annul a marriage when a husband refuses to terminate it with a get (religious divorce). He expressed his opposition by, among other things, posing a thought experiment. Imagine a world in which this proposal is accepted. The Talmudic tractates of Kiddushin and Gittin which discuss how a marriage is effected and ended would become irrelevant, as would Yevamot which discusses levirate marriage. Fundamental halachic principles that have guided the Jewish community throughout the ages would be set aside, rendered irrelevant by activist rabbis.

How do members of his audience, rabbinic alumni of Yeshiva University, expect to survive as Orthodox rabbis if specific halachic concepts are revised wholesale? Where would the tradition be, the continuity from past generations? How can they claim to carry on the mesorah? Entertaining the possibility of revising Talmudic halachah at a rabbinical conference is as nonsensical as discussing the adoption of communism at the Republican National Convention. It is a conversation about suicide for the Orthodox community, the self-destruction of halachic Judaism.

Halachic Reality

The Rav knew very well the problems facing pulpit rabbis, the social, political, cultural and economic pressures. He saw the challenge of intermarriage and the tragedy of mamzerut (illegitimate children), often in questions passed on to him by his students. Yet the answer, he declared, does not lie in reformist philosophy or convenient misinterpretations of halachah. The problem of mamzerut is unsolvable; it is an explicit Biblical verse that we cannot set aside. It is tragic, but it is a religious reality. We cannot abandon our halachic heritage, our timeless Biblical and Talmudic mandates, for any reason. We cannot allow a married woman to remarry without a get no matter how tragic the situation. Nor can we allow a kohen to marry a convert. We dare not attempt to cover up halachic realities, however heartbreaking, with extraneous and deviationist interpretations.

If we remain firm in our principles, we may appear inflexible and therefore lose popularity. However, people will respect us for our consistent stand. If we start bending halachah with external schemes, we will garner neither love nor respect. The Almighty summons us to live halachically, and we have no other choice. This is Torah; this is surrender; this is kabbalat ol malchut Shamayim.

The Rav told the story of a young man and woman who sought his assistance. She was a convert who later fell in love with this young man, whose increased interest in Judaism she sparked. The two became engaged and he visited his grandfather’s grave, where he discovered that he is a kohen. What could the Rav do? A kohen may not marry a convert and therefore, tragically, this couple could not wed. However, we must unhesitatingly surrender to the will of the Almighty. With sadness in his heart, the Rav shared in the suffering of this woman who had to lose the beloved man she helped bring back into the fold. She valiantly walked away from him, surrendering to the Almighty’s will.

Responding within Limits

Judaism has historically been and continues to be responsive to the needs of both the community and the individual. But, the Rav taught, it has its own orbit and its own speed, it responds to a challenge with its own criteria and principles. The Rav followed the rabbinic traditions of his grandfather, Rav Chaim, who believed in striving for leniency based on the personal needs of the inquirer. However, even Rav Chaim’s skills had limits. When you reach the boundary of halachah beyond which you dare not pass, you must say: “I surrender to the will of the Almighty.”

Torah study is a yoke because we lack the authority to change its laws. Shinuy, change, is unacceptable. Chiddush, innovation, creative interpretation, is the very heart of halachah. It is the engine of halachic continuity throughout the ages. But these chiddushim must be within the discipline, internal to the system of halachah and not originating from the outside. They must soberly represent the humble and fearful surrender to the Torah we have learned from the Sages. They must respect the past and continue the mesorah whose responsibility of transmission rests on our shoulders.

This influential speech was a watershed event in recent rabbinic history. With it, the Rav offered a brief but remarkable philosophy of creativity in Torah study and a guide for halachic change and conservation. We would do well to incorporate the Rav’s Torah philosophy into our own worldviews and allow his sage guidance to steer our way through the difficult situations we face.

Rabbi Steven Weil is Senior Managing Director of the OU.