In The Limelight

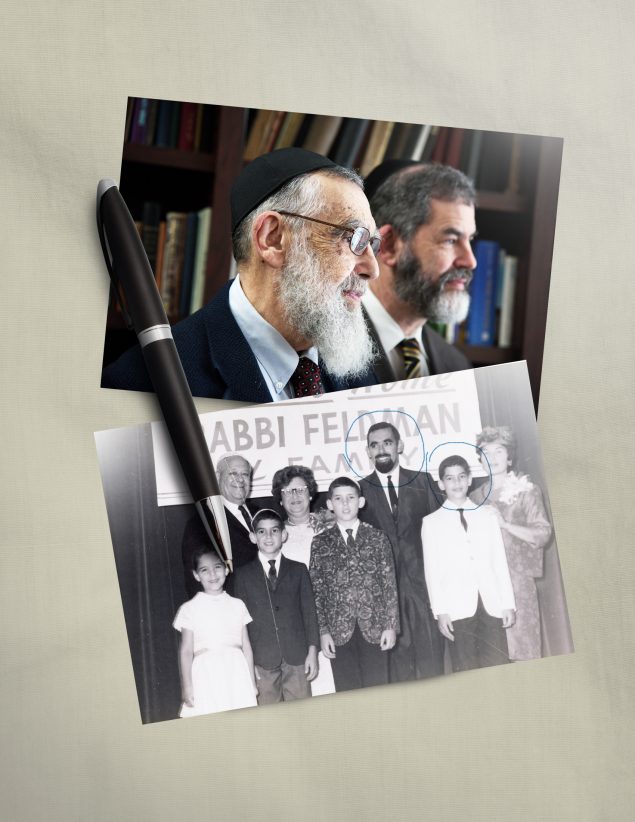

Top: Rabbis Emanuel and Ilan Feldman. Photo: Harold Alan Photographers/Harold Schroeder

Bottom: The Feldman family, circa 1960. Courtesy of Ella Szczupak

As soon as President Trump entered office, his son Barron became public property as “First Boy.” The media analyzed Barron’s every move and rumors ran rampant. His childhood was up for grabs; his life was no longer his own.

Growing up as the child of any influential person poses challenges, and the children of shul rabbis, prominent lay leaders and other important community figures are no exception. I spoke with the sons and daughters of well-known rabbis, rebbetzins and community leaders about how their childhoods in the limelight shaped their worldview, their self-image and their lives.

Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter is professor of Jewish history and Jewish thought at Yeshiva University, senior scholar at the Center for the Jewish Future at YU, and the son of the late Rabbi Herschel Schacter, a national Jewish leader and revered rabbi of Mosholu Park Jewish Center in the Bronx. He realized early on that his father was unlike other fathers. In some ways, Rabbi Schacter enjoyed his privileged status. He watched as his father stood at the synagogue bimah and spoke before hundreds of people. While the congregation sang Adon Olam, he got to sit on his father’s lap, and he relished the special attention.

But his status also meant greater expectations. When Rabbi Schacter was eight years old, his father found him playing in front of the shul after Shabbat morning davening. He asked his son where he had been during the derashah. He wasn’t happy with the answer.

Sometimes the expectations are not from the rabbi or his wife; they come from the community.

“During shul, I’d be playing outside with other kids,” says Esti Schwartz, twenty-three, the daughter of Rabbi Allen Schwartz, the longtime rabbi of Congregation Oheb Zedek on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. “People would come over and only yell at me and my brother, because we were the rabbi’s kids.”

Nechemia Katz* [*pseudonym] the son of a rav who is involved with assisting kids at risk, admits he wasn’t the best behaved child, but feeling pressured to keep up a good-boy image, he played the part. He didn’t want to risk embarrassing his family.

But not every child of a rabbi feels the stress of having to live up to a certain image. “My parents expected me to act a certain way, not because I was the son of the community rav, but because they wanted me to be a mensch,” says Rabbi Ilan Feldman, the son of Rabbi Emanuel Feldman, founding rav of Congregation Beth Jacob of Atlanta, Georgia.

I felt there was no way I could possibly ever project myself as a rabbi in a world so full of my father’s presence. How could I ever do anything in my life that could remotely resemble what he did?

Similarly, Dr. Rivka Press Schwartz, the daughter of Rebbetzin Zlata Press, the noted lecturer and principal of Bnos Leah Prospect Park Yeshiva, a girls’ high school in Brooklyn, claims she “didn’t have the ‘preacher’s kid’ problem.”

“I don’t think my identity was shaped by being my mother’s child,” she says. “My mother encouraged us to speak our minds. She would engage us in serious conversations about [consequential] topics and raise thought-provoking questions—taking our responses seriously.”

In turn, when her mother suggested that she consider scrapping her plans to become a university professor, and that teaching high school would prove more fun and more religiously fulfilling, she took her advice. Today Dr. Schwartz is a high school administrator and popular lecturer.

A Sense of “Otherness”

The perception that the offspring of rabbis are a different breed leaves some with a persistent feeling of “otherness.” Esti found herself frequently fielding questions about kashrut from her schoolmates. To her mind, in the same way that an accountant’s child isn’t necessarily good at math, being the rabbi’s daughter didn’t make her a better davener than her peers or an expert on halachah.

Similarly, throughout his childhood, Rabbi Feldman felt pigeonholed as the un-athletic rabbi’s kid. “I was always picked last for the team,” says Rabbi Feldman. “There was a feeling of futility that I would never fit in,” he says.

Time Management for Rabbis

Much like a medical doctor, a rabbi is constantly on call. The time pressures make it nearly impossible to carve out quality time for his family. Dr. David Pelcovitz, professor of psychology and Jewish education at YU’s Azrieli Graduate School of Jewish Education, sees this as the major challenge facing a rabbinic family.

“Rabbis have to be mindful about finding that exclusive family-focused, text-free, phone-free, one-on-one time with one’s wife and children,” he says.

During his early years as shul rav, Rabbi Schwartz delighted in hosting a guest-filled Shabbat table. His eldest daughters, however, weren’t so pleased; they complained that they didn’t enjoy Shabbat and that they didn’t feel they were in their own home. Thereafter, Rabbi Schwartz and his wife designated Friday nights as family-only time.

Left: Rabbi Herschel Schacter. Photos courtesy of Rabbi J.J. Schacter

Right: Rabbi Herschel Schacter, Rabbi Ruwin Jona Weisbord, a”h (Rabbi J. J. Schacter’s late father-in-law) and Rabbi J. J. Schacter at his wedding, September 4, 1972.

By the time Esti came along, her childhood included “special Tuesdays with Abba.” Every other week, she and her younger sister enjoyed exclusive time playing board games with their father. Nonetheless, certain sacrifices had to be made.

“I remember days when we were about to go out bowling together, and my father got an important phone call. We had to wait another twenty minutes,” says Esti. “It’s just something you learn to be patient about.”

While spending quality time with one’s children is a challenge facing all parents, in a study conducted back in 1988 and written up in Tradition, clinical psychologist Dr. Irving Levitz found that 70 percent of rabbis’ children in his study believed that their fathers were “over-involved with synagogue life.”

During the week, Nechemia’s father ran Jewish educational programs. He also led several Shabbatons. Although Nechemia appreciated his father’s demanding work, he missed him.

“A child needs a mother and father,” says Nechemia. “I’ve seen people involved in the kehillah who don’t make time for their families. For some, [communal work] can become an obsession. I don’t think [the obsession with work is] necessarily unique to someone prominent in the community. It could be a lawyer or doctor with long hours outside the home, or the head of a major investment firm. They’re not putting their families first; they’re putting themselves first.”

One rabbi’s child I spoke with tells a poignant story. “Towards the end of my father’s life when he was too ill to engage in conversation, my mother told me that he was sorry he didn’t devote more personal attention to me while I was growing up. I [told my mother], ‘I’m sorry too.’”

Making Time

Rabbi Schacter grew up knowing he had a world-famous and very busy father. On April 11, 1945, the senior Rabbi Schacter was the first US Army chaplain to enter the Buchenwald concentration camp to liberate the survivors. Anguished by what he saw, he remained in Buchenwald for two and a half months, comforting the broken, displaced Jews and giving them hope for the future. He also arranged for and led a Kindertransport from Buchenwald to Switzerland.

After his return to the States, he went on to become president of Mizrachi of America and chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations. He was president of Mizrachi-Hapoel Hamizrachi, founding chairman of the American Jewish Conference on Soviet Jewry, chairman of the Chaplaincy Commission of the Jewish Welfare Board, and director of rabbinic services at YU.

His young son felt enormously proud of his father’s accomplishments. And he cherished the opportunity to spend “one-on-one” time with his father. As a teen, he would learn with him for three to four hours at a clip. His father also came to visit him numerous times during the year he spent learning in Israel, taking him to meet Rabbi Shlomo Goren, the then chief rabbi of the Israel Defense Forces, the Sephardi and Ashkenazi chief rabbis and Menachem Begin.

“My connection to my father was through these public experiences,” says Rabbi Schacter. “[I believe] he expressed his love by taking me along on those visits.”

Sharing the Mission

To Slovie Jungreis Wolff, educator, author, international lecturer and daughter of the late Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis, private and public life were one and the same. Their home was abuzz with communal activity and everyone got involved.

On Purim, the entire family would pile into the car; each member had a job to do. One sibling checked the list of two hundred mishloach manot recipients; another ran from door to door to deliver Hungarian pies lovingly made by their Bubby, a Holocaust survivor, and to wish recipients a happy Purim while describing the meaning of the holiday. The family would then drive back to the house to reload the car, and then take to the road again.

“My parents’ mission was our mission,” says Slovie. “This was our life. We were strengthening Yiddishkeit in America, carrying the torch from the Holocaust—continuing what [those who perished] could not.”

Dr. Pelcovitz stresses that parents who include their children in the causes they believe in are not only sending the message that this is a worthwhile way to invest one’s energies—they are helping the message become an integral part of their children’s identity. As the son of Rabbi Raphael Pelcovitz, beloved rabbi emeritus of Congregation Kneseth Israel in Far Rockaway, New York, Dr. Pelcovitz remembers setting up the room and preparing the sefarim for his father before he would deliver a shiur. Over the decades, the father and son have continued to collaborate—they co-wrote several articles and books on parenting and enhancing Jewish life.

Rebbetzin Tehilla Jaeger, daughter of the late Rabbi Shlomo Freifeld, legendary educator and founding rosh yeshivah of Sh’or Yoshuv Institute in Lawrence, New York, is convinced that the message of working for the klal was “mixed into her baby food.” She watched her parents transform the lives of hundreds of Jewish youth, products of the sixties and seventies hippie generation who were searching for a deeper meaning.

As a young girl, she remembers regularly setting and cleaning up tables for their Shabbat and yom tov guests and sharing her bedroom with the constant flow of ba’alot teshuvah sleeping over. Her father, insisted, however, on giving his hardworking rebbetzin periodic Shabbatot off, taking the children shopping for take-out instead. “There had to be time to reenergize in order to go back into the trenches,” says Rebbetzin Jaeger. “That was an important lesson for me.”

My Father/ Myself—Choosing One’s Own Path

As adulthood draws near, adolescents begin to contemplate their place in the world independent of their parents.

Nechemia knew his parents expected him to go into the rabbinate. He felt pushed. He pushed back harder.

“Becoming a rabbi was never my path; you really have to have a certain kind of personality,” he says. “The conflict put a strain on the relationship. I became a troublemaker, and was not interested in religion. I was trying to show my independence. As I matured, I came back [to religious life]. Some don’t.”

“It’s never wise to push a child to become something he is not,” says Dr. Pelcovitz. “Rav Yeruchom Levovitz, the revered mashgiach of Mir Yeshiva in Poland, taught that when Yaakov Avinu gave the berachot to his children [the shevatim], he did so according to their individual paths. Rav Levovitz said if you give a berachah to a child with your own dreams in mind, it’s like watering a plot of earth that has no seeds in it. It’s a berachah l’vatalah. Good parenting is about letting your child follow his own aspirations, his own potential, his unique spark.”

Dr. Schwartz’s independent spirit was already evident in her teens when she attended the high school where her mother was the assistant principal—and in charge of enforcing school discipline. Her mother maintained a clear division between her public role and her role as a parent, which didn’t always work for her daughter’s benefit—especially during a school dress code run, when Dr. Schwartz decided to wear a top with NYPD printed across the front.

“My mother pulled me out of class and sent me home to change,” she says. “I still have the shirt. I kept it as a valuable memento of my wayward youth.”

Continuing the Legacy

Despite the challenges of growing up as children of celebrated community figures, virtually every one of the sons and daughters I spoke with chose careers involving service to the klal—even though for some of them, doing communal work was initially the last thing on their minds.

“I felt there was no way I could possibly ever project myself as a rabbi in a world so full of my father’s presence. How could I ever do anything in my life that could remotely resemble what he did?” says Rabbi Schacter, who originally planned to become a Jewish historian and scholar. But while he was learning at Torah Vodaath, his father urged him to get semichah saying, “You never know.”

After spending four years on a fellowship at Harvard University, earning him a PhD in Near Eastern languages, the gnawing feeling that he wasn’t doing enough for the Jewish community prompted him to join the rabbinate.

Rabbi Schacter became the first rabbi of the Young Israel of Sharon in Massachusetts, where he succeeded in creating a vibrant Torah community. He went on to serve as rabbi of The Jewish Center in Manhattan for nineteen years and, subsequently, dean of the Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Institute in Brookline, Massachusetts.

Rabbi Feldman also had little interest in pursuing a career in the rabbinate. Like Rabbi Schacter, he set his sights strictly on Torah scholarship. When an assistant rabbi position opened up at his father’s shul, the kehillah urged him to fill it. He acquiesced and eventually succeeded his father as rav upon his father’s retirement in 1991, but not without some apprehension. “The criticism of the rabbi can be intense,” he says. “It took a while for me to establish my own style.”

Despite his initial concerns, Rabbi Feldman continues to build on his father’s work, bringing a community kollel to Atlanta, now known as one of the leading centers of Orthodox Jewish life in America.

Both of Esti’s older sisters, who promised themselves they would never marry a rabbi, did in fact marry rabbis. One of her brothers just received semichah and the other is in the process of doing so.

Despite the expectations, visibility and sacrifice, these children of rabbis or high-profile rebbetzins saw close-up what it means to take a community under one’s wing, and to dedicate one’s life to uplifting others. Rabbi Schacter saw this in the most profound way.

In the summer of 1967, he was walking with his father on King George Street in Jerusalem. Suddenly, they noticed two frum young men coming towards them. As the men approached, they stared at his father and then ran towards him, threw themselves on him and began weeping uncontrollably. Then, without saying a word, they dried their tears, pulled themselves away and continued walking.

“I knew exactly what that was,” says Rabbi Schacter. “They had been children on the Kindertransport from Buchenwald. [That incident] was a microcosm for the intense power, the impact that my father had in saving these lives. He gave them chizuk, a sense of hope, their Judaism. He gave them back their humanity.”

When Rabbi Schacter was five years old, his father went away for seven weeks as part of the first delegation of American rabbis to visit Jews trapped in the Soviet Union. He asked his mother, “Vi iz Tatty?” [“Where is father?”] She answered with the familiar refrain. “Tatty iz gegangin helfen Yidden.”

“That’s huge, to be taught this as a little boy,” he says. “My father went to help Jews.”

Bayla Sheva Brenner is an award-winning freelance writer and a regular contributor to Jewish Action. She can be reached at baylashevabrenner@outlook.com.