Jerusalem Reunited

Introduction By Faigy Grunfeld

“The armies of Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon are poised on the borders of Israel . . . to face the challenge, while standing behind us are the armies of Iraq, Algeria, Kuwait, Sudan and the whole Arab nation. This act will astound the world. Today they will know that the Arabs are arranged for battle; the critical hour has arrived.” —Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, May 30, 1967

And thus began the Six-Day War. A war school children know nothing of, millennials know sadly little and baby-boomers whisper about in reverential tones.

A war that affirms the Divine influence. A war that acts as a metaphor for 2,000 years of inexplicable, incomprehensible Jewish survival.

Six short days, when everything everyone thought or imagined was turned inside out.

Why war? Oh, so many reasons . . .

– Syrian instability after the breakup of the United Arab Republic

– The newly formed PLO

– Egypt’s blockade in the Straits of Tiran

– Soviet influence in the region

– The dawning realization that this experiment of a Jewish state was not going away

– Water, oil, history . . .

All of which might explain the on-stage shuffling and maneuvers, but none of which encapsulates the driving force of it all, the menacing shadow of our existence which has clung to us without reprieve.

On the first day of the war, Israel launched an air strike that destroyed the majority of the Egyptian Air Force on the ground.

June 5. War. Surrounded by mobilized hostiles on all of its borders, the Israeli air force brazenly throws the first stone, demolishing Egypt’s fighter jets while still on the tarmac. Vulnerable and unshielded, the Egyptians are driven back, through the Gaza strip, the Sinai Desert, right up to the Suez Canal. Jordanian forces begin shelling West Jerusalem, to which the Israelis respond with a crushing counterattack, capturing East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

June 7. Proposed ceasefire. Jordan hurries to accept the terms, with Egypt trailing one day behind.

June 9. Syria continues to shell Israeli farmers and villages from its advantaged position in the Golan Heights. Another day of fighting brings the Syrians to the table and the ceasefire is complete.

The war’s results?

– Israel more than tripled in size

– 777 Jewish deaths

– An exacerbated refugee crisis

– A boundary dispute with no solution

– A rabid enemy that populates nearly a quarter of the globe

For there is no greater provocateur than a Jewish victory.

As you read through the personal accounts below, of those who lived through those terrifying days of uncertainty, fear and hope, relive not just the terror, but also the wondrous Maccabean-like miracles of those extraordinary six days. Relive the sense of awe and wonder that Jews the world over—religious and secular alike—felt then, and reaffirm your own faith in the eternity of the Jewish people. Am Yisrael Chai.

Faigy Grunfeld is a history teacher living in Detroit, Michigan.

Design: Andres Moncayo

Special thanks to Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski for researching and assisting in preparing this special section.

All photos courtesy of the Israel Government Press Office. Individual photographers, where required, are specified in the captions.

Memories of the Six-Day War

Rabbi Menachem Porush

On that Tuesday when Hussein [King of Jordan] flew to [Egyptian President] Nasser, the atmosphere in the Knesset was that of Tisha B’Av—without exaggeration. Military experts felt that given the mobilization of Egypt’s forces, and those of the other Arab states—particularly their air strength—the outbreak of war could chalilah, destroy us . . . .

The preparations in the hospitals were dreadful—the sick were removed to make place for the war casualties. Hundreds of graves were dug . . . The streets were emptied of men of military age—they had all been called up . . . .

The Bnei Yeshivas donated blood—they gathered the crops, they worked in the hospitals . . . and when troops marched by the shuls and yeshivos they called out: pray for us.

Day and night groups said Tehilim—the cries tore the heart. Women stood alongside every Aron Hakodesh, crying and pleading for Divine Mercy. And the war began.

The center of the Land, Tel Aviv and its environs, were most exposed to the danger of air attack; from time to time the sirens wailed and people rushed to the shelters. Many places were badly hit . . . .

Fierce battles were going on in the Negev and Sinai. One hundred and eighty tanks were in direct confrontation for 36 consecutive hours. War correspondents who had covered great wars agreed that they had never seen such fierce face-to-face fighting . . . .

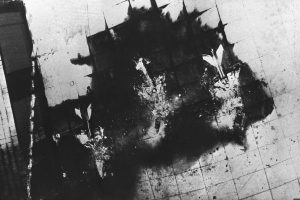

A layer of smoke hangs over the Old City of Jerusalem from the exchange of fire between Arab and Israeli troops during the Six-Day War.

Yerushalayim stood embattled face-to-face with the enemy, surrounded on all sides by Jordanian forces . . . We were under a rain of shells and horrible explosions. Many fell wounded—many fell dead. The hits were devastating—they were calculated to strike at sensitive areas. Yerushalayim was under the threat—G-d forbid—of destruction, were it not for the super-human bravery of the men of the Israel Defense Forces, their demonstrations of bravery and strength, their indescribable self-sacrifice. Soldiers gave their lives, knowing that they were saving many others. There is no parallel to the miracle, and to the wondrous achievements of our Air Force, in destroying the Egyptian Air Force in the early hours of the campaign. Israeli planes evaded enemy radar and were undetected as they approached enemy airfields . . . thus being able to destroy their planes and remove the threat of massive air-attacks. This completely upset Egypt’s battle plan which was geared to destroying the major cities and only then pitting into battle the infantry and armor . . . .

These were great days—awesome days. For generations fathers will tell their sons of the Mighty Acts. But . . . “Who can express the greatness of G-d, who can tell His praise?” . . . .

One could talk for a thousand nights and not do justice to the miracles and wonders we saw . . . .

Those who were optimistic about the outcome of the war felt they would be fortunate if they remained alive. They could not foresee that we would enlarge our boundaries Westward and Eastward, to the North and to the South. This we dared not even hope for. We did not dream—it occurred to no one at all, that we would yet merit the freeing of the Holy Places: the Kosel Ma’aravi, the Me’oras Hamachpelah, the Tomb of Rachel, Har Hazaisim, the graves of Yosef Hatzadik, Shmuel Hanavi, Shimon Hatzadik. Who could have thought that the Har Habayis, the site of the Beis Hamikdosh would be in our hands—that we would have to caution Jews not to enter the site till the coming of Moshiach? The Har Habayis in Jewish hands—it still seems unbelievable.

Who can record our feelings as we entered the gates of Yerushalayim, standing opposite the Har Habayis and approaching the Kosel Ma’aravi; or as we entered Me’oras Hamachpelah, which a Jew was forbidden to enter for the last 800 years?

Reprinted with permission from the Jewish Observer, “Extracts from a Personal Letter Written by Rabbi Menachem Porush, MK” (September 1967): 5-7. Courtesy of the Agudath Israel of America Orthodox Jewish Archives

Commander Motta Gur and his brigade observe the Temple Mount from their command post on the Mount of Olives just prior to the attack of the Old City.

Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe

In May 1967, as the armies of Egypt and Syria prepare to attack Israel, and Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser announces, “Our basic objective will be the destruction of Israel,” the Jewish world falls into a state of great anxiety, even panic, fearing massive Jewish deaths only twenty-two years after the Holocaust. Inside Israel, many Jews with foreign passports flee the country, but the Rebbe tells people to remain in Israel and to have no fear.

On May 28, just over a week before the war begins, the [Lubavitcher] Rebbe, speaking before an audience of many thousands, proclaims that Israel will soon emerge from the current situation with great success: “There is no reason to be afraid. I am displeased with the exaggerations being disseminated and the panicking of the citizens in Israel.” His optimistic pronouncements are headlined in Israel’s newspapers: “God Is Defending the Holy Land, and Victory Will Come Soon” (Yediot Ahronot, May 31, 1967).

From Joseph Telushkin, Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History (New York, 2016), 493.

Rabbi Shlomo Goren

Since I knew that on this day we would be liberating the Old City and reaching the Kotel, at around 4:30 in the morning I hurried to the home of my father-in-law [Rabbi David Cohen, the “Nazir of Jerusalem”], who had a synagogue attached to his home. “I need your synagogue’s shofar,” I told him when he opened the door to the sound of my knocking. “We are going to liberate the Kotel!” He became so emotional that he began to cry, but he climbed onto a table (the shofar was tucked away high up in a cupboard), and gave me the shofar . . .

Brigadier Rabbi Shlomo Goren, chief rabbi of the IDF, carrying a sefer Torah and blowing the shofar, surrounded by IDF soldiers on the Temple Mount. Photo: Eli Landau

According to Jewish law, when Jews go out to battle, they blow trumpets or shofars to assure their victory, as the Torah states: “And if you go to war in your land, against the enemy that oppresses you, then you shall blow an alarm with the trumpets; and you shall be remembered before the Lord, your God, and you shall be saved from your enemies.” It was for this reason that I had brought a shofar with me. The moment we drew close to the gate, I began blowing the shofar, sounding it loudly in this war for the liberation of Jerusalem . . . . I began to utter a prayer in between shofar blasts and shouted to the soldiers, “In the name of God, take action and succeed. In the name of God, liberate Jerusalem, go up and be successful.” I kept shouting the entire time, until we were right on top of the Temple Mount, where I found Motta Gur [commander of the brigade that captured the Old City] standing surrounded by his soldiers. I had prepared a proclamation, which I then recited on the Temple Mount:

In honor of the liberation of the Old City, the Kotel, and the Temple Mount from the enemy legions on 28 Iyar, 5727 on the Jewish calendar.

Israeli soldiers, beloved of the nation, decorated with courage and victory, may God be with you, valiant heroes. I am speaking to you from the plaza of the Kotel, the remnant of our Holy Temple. “Comfort My people, comfort them, says your God (Isaiah 40:1). This is the day we have waited for . . . . The city of God, the place of the Temple, the Temple Mount and the Kotel, the symbol of the messianic redemption of the nation, have been redeemed this day by you, heroes of the Israel Defense Forces. Today you have fulfilled the oath of the generations—“If I forget you, O Jerusalem, may my right hand forget its cunning.” Indeed, we have not forgotten you, Jerusalem, our holy city, home of our glory, and your right hand, the right hand of God, has made this historic redemption . . .

From Rabbi Shlomo Goren, With Might and Strength: An Autobiography (New York, 2016), 326-327.

“Blessed are You, O Lord, our God, King of the universe, who hast kept us in life and has preserved us, and has enabled us to reach this season.”

—Brigadier Rabbi Shlomo Goren, chief chaplain of the IDF, as he stood surrounded by ecstatic young Jews at the Kotel Ma’aravi, 28 Iyar 5727; June 7, 1967.

From left: General Uzi Narkis, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin enter through the Lion’s Gate into the Old City. Photo: Ilan Bruner

Defense Minister Moshe Dayan

This morning, the Israel Defense Forces liberated Jerusalem. We have united Jerusalem, the divided capital of Israel. We have returned to the holiest of our holy places, never to part from it again. To our Arab neighbors we extend, also at this hour—and with added emphasis at this hour—our hand in peace. And to our Christian and Muslim fellow citizens, we solemnly promise full religious freedom and rights. We did not come to Jerusalem for the sake of other peoples’ holy places, and not to interfere with the adherents of other faiths, but in order to safeguard its entirety, and to live there together with others, in unity.

Statement by Moshe Dayan, June 7, 1967.

Rabbi Moshe Feinstein

Since the generation of King David was a righteous one which believed in God, David could request from God that they be victorious in war through natural means, because even if they were to fight with weapons and all the methods of war and overcome and defeat their enemies, all would recognize that it was God who was responsible for their victory. But in the generation of King Asa, in which the people were not of such great faith, Asa feared that if they would pursue the enemy and overcome it and were then victorious, the people would say that it was due to their own strength, and therefore he requested that God should cause the enemy’s downfall before they even reached them. And Yehoshafat, who was concerned about the diminishment of faith in his generation, feared that even if they were just to pursue the enemy, they would say that they were victorious on their own, and therefore he prayed that God should smite them and he would only recite a song. And Hezekiah feared even reciting a song, lest they say, God forbid, that this served as a magical form of helping, and therefore he said that he did not have the strength to recite a song.

All the more so in our generation, in which those of small faith have increased, we require miracles exclusively, so that perhaps the people will recognize that it is God who is doing this. And so, thank God, this has been fulfilled, and He has produced the victory over Arabs far greater in number, who also had the assistance of a major empire for their weaponry, much greater than our state in the Land of Israel, and yet in just four days, they defeated all of the Arab nations and Egypt, in the time from Monday to Thursday, and we hope that He will send the King Messiah soon, and all Israel will recognize that “the Lord is a man of war” (Exodus 15:3).

Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, Darash Moshe, “Parashat Eikev” (Beth Medrash L’Torah V’Horaah, 1988). [Translation by Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski]

Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm

Hard-boiled Israelis, even supposedly non-religious ones, have understood the religious dimension and significance of these events better than American Jews, even religious ones. Indeed, it had to be so; they were ready to, and did, give their lives, while we gave support. And, somehow, faith has closer ties to blood than to cash, no matter how plentiful, how abundant, how generous. No wonder that a radio correspondent told us over the airwaves that though he was never religious and hardly recognized his Jewishness, when he approached the Kotel Maaravi, the Wailing Wall, he rubbed his cheek against it in affection and cried uncontrollably. A visitor, recently returned, told me that the day after the capture of the Wall, Jews who had never in their lives made a blessing stayed three hours in the hot sun in order to be able to pray in tefillin at the side of the Kotel Maaravi. And the press informed us today that yesterday, the first day of Shavuot, tens of thousands of Jews made the pilgrimage to the Wall . . . .

Even observant religious people usually possess an element of doubt within their faith. We use this doubt to excuse many of our transgressions, and we excuse the existence of this doubt by saying that had we lived in the age of the prophets or the age of miracles or the age of revelation, we would be sufficiently persuaded and convinced to be able to live according to the highest precepts of our faith, but that the absence of any such evidence justifies this seed of doubt. Were we exposed to the same wonders as was Israel of old, “and Israel saw the Egyptians dead at the shore of the sea,” then we too would react as they did: “and they believed in the Lord and in His servant Moses” (Ex. 14:31).

Such was the justification we offered ourselves for our doubt and our laxity heretofore. Now, we can no longer avail ourselves of that luxury. For we have seen, as did Jews in very special moments of history, ha-yad ha-gedolah, the “great Hand of the Almighty.” Through electronic eyes and ears, each of us has been a personal witness to the great miracle, the great revelation of 1967.

Excerpted from Rabbi Norman Lamm, “O Jerusalem!,” a lecture delivered at The Jewish Center on the Upper West Side of Manhattan on June 15, 1967 (the second day of Shavuot), http://brussels.mc.yu.edu/gsdl/collect/lammserm/index/assoc/HASH012a.dir/doc.pdf.

Rabbi Bezalel Zolty

There is a great misconception among us. We think that the ones who need to be awakened to repentance are our brothers who are called “secular,” but we, the religious Jews, and especially the rabbis, we have no connection to such a thing—after all, we are observant Jews; we pray three times a day. However, the truth is we have seen that specifically those whom we call secular have been awakened to repentance, but those whom we call religious have had less of an awakening, because we are accustomed to thinking that we are perfectly fine. This, in my opinion, is the greatest mistake, and we cannot influence others if we ourselves are not awakened to greater deeds and repentance.

Speech delivered by Rabbi Bezalel Zolty to the members of religious councils at Hechal Shlomo: The Center for Jewish Heritage in Jerusalem (August 7, 1967). From Rabbi Shai Hirsch, “Anthology for the Salvation of the Six-Day War and Liberation of Jerusalem” [Hebrew], available at http://www.yeshiva.org.il/midrash/31494. [Translation by Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski]

Rabbi Chaim Shmuelevitz

I am not a prophet. I am a simple man, but it is clear to me that were we to have a prophet today, he would declare: “Your throne is established of old! Praise the Lord, all nations; laud Him, all peoples. For His mercy is great toward us; and the truth of the Lord endures forever. Hallelukah. The Lord is a man of war, the Lord is His name.” The Vilna Gaon wrote in a letter to his mother: “If I merit to stand beside the gates of Heaven, I will pray for you.” He did not merit it, but we have merited it, and with God’s help we will stand beside Heaven’s gates—the Western Wall—to pray on behalf of the Jewish people. We will give praise and thanks, “Your throne is established of old.”

Speech delivered by Rabbi Chaim Shmuelevitz in the Mir Yeshivah, June 1967, ibid.

Ponovezh Yeshivah

“After the victory in the Six-Day War, they recited Hallel in the yeshivah for two years on the day Jerusalem was liberated. Following the Six-Day War, there was an eruption of Religious Zionist sentiment in the Ponevezh Yeshiva. In its wake, students sought to transfer to Mercaz HaRav, and there were those who wished to be drafted into the army.”

Rabbi Gavriel Botbol, a student in the Ponevezh Yeshivah in 1967, ibid.

Front row, from left: General Uzi Narkis, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin and General Rehavam Zeevi in the Old City. Photo: Ilan Bruner

Michael Oren

“Even for these very secular kibbutznicks, people who’d never been inside a synagogue in their life, the feeling was overwhelming. Chief of Staff Yitzchak Rabin comes down and Moshe Dayan, the defense minister, comes down, both very secular Jews; they read Psalms at the Wall and wept. It was just overwhelming for anybody.”

Michael Oren, American-Israeli historian and author of Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East in conversation with Eric Westervelt on “Six Day War: Jerusalem, United in Theory,” NPR, Morning Edition, June 6, 2007, http://www.npr.org/2007/06/06/10758103/six-day-war-jerusalem-united-in-theory.

View From Denver: I.T. and I Rode the Crest in 1967

By Hillel Goldberg

“I.T.,” I called my best friend in college. I.T. and I had quite a reputation for activism, having (among other projects) saved the JTS library after it suffered a devastating fire in 1966. But that’s a story for another time.

The Six Day War broke out June 5, 1967. Throughout May, roughly a month before the war, everyone knew the war was coming. UN Secretary General U Thant pulled the UN troops out of the Sinai Peninsula, leaving Israel exposed; Nasser bragged about driving the Jews into the Mediterranean Sea; the tension was so thick it could be cut with a knife.

I was a junior at Yeshiva College in Manhattan; I.T., a sophomore. The word was out that when the war came, Israel’s farmer soldiers would leave their farms and the crops would rot for lack of manpower. The Arabs could kill the Israeli economy if they tied up Israel in a war, even if the Arabs ultimately lost.

So went the scenario. It was extremely plausible. No one—not a single eminence in Israel’s military or political echelon—predicted a six-day victory, let alone a victory at all.

And so, I.T. and I had the idea of sending volunteers to Israel’s kibbutzim. Don’t ask me how we passed our courses that semester, for this is what we did: First, we convinced the phone company (without permission from the university) to wire our dorm rooms with multiple lines. Then we went to work. This was the agenda: To convince as many students as possible to volunteer for the summer on Israeli kibbutzim. The heavy cloud of impending war meant that we had to convince not only the students, but often their parents and the Israeli authorities. We also had to put in place a system for a quick acquisition of passports.

And quick reservations on the increasingly rare seats open on the few planes still flying into Israel.

Not to mention, money to pay for it all.

We asked no permission from the Jewish Agency, which, officially, was responsible for sending volunteers to Israel. We just acted.

As word got out, money started pouring in. Rabbis raised money in their synagogues; people came in off the street; students pulled from their pockets or parents. People would literally hand us envelopes of cash, at first once or twice a day, then many times daily. We had credibility, for we actually succeeded in getting students to Israel. First a few, then a trickle, and finally a flood.

It was complicated.

The lines for passports were long. We did not accept that. Upon pressing the American authorities, we discovered that, by law, a citizen has a right to a passport within 24 hours (at least that was the law then). We pressed our rights to the fullest.

An Israeli artillery unit bombarding the northern sector of the Suez Canal, June 8, 1967. Photo: Micha Han

At first, “we” was I.T. and me. Quickly, the cadre of activists grew. By the time June 4 rolled around, we had several groups of student activists: experts in passport procedures; lobbyists at the Jewish Agency, who needed to approve the volunteer applications; and lobbyists at the airlines, who were very choosy [as] to whom they issued seats.

Our money spoke. For every student who was willing to volunteer, we had the money for the airline ticket and the passport.

At a certain point, the Jewish Agency turned over the keys to its offices. We now had as much space as we wanted to do our work, but the hub remained at our college dorm rooms. Morning, noon and night, they were a-buzz with activity.

Each potential volunteer was a challenge. This one wanted to go, but his parents didn’t agree; this one’s parents agreed, but there was no current, valid passport; this one didn’t want to miss classes, and needed to be convinced that saving Israel was more important than grades for one term. I don’t remember how many tens of thousands of dollars went through our hands; I don’t remember how many Yeshiva students actually volunteered. I do remember that we had several students on the last flight out of New York before the war.

In some ways, it was a typical ‘60s effort: Think for the moment; everything for the cause; nothing for daily responsibilities—and give the authorities fits (the authorities at YU, the Jewish Agency, the State Dept.). In other ways it was not typical: no drugs or promiscuity, just an idealistic, positive effort. Rather than rail against the establishment, we bent it to our will. The bottom line was that Israel trumped all.

Slam.

Darkness.

In a moment, we were shut down.

The war came.

Our office was suddenly irrelevant.

The Yeshiva shuls filled with students and with rabbis saying Psalms, as fervently as I’ve ever heard.

We bit our nails.

We waited.

There was a news blackout for the first day or two of the war.

Suddenly.

It was clear.

Israel had won—and won in a lightning flash.

There were no farmer-soldiers pulled from the kibbutzim for an extended time.

All the student volunteers we sent would now have a memorable experience, basking in the afterglow of the miraculous Israeli victory. They would not be slaving away on the kibbutzim.

They loved it.

Whatever the level of Israel-consciousness at Yeshiva before the war—and obviously, it must have been high; otherwise all those students would not have volunteered—it was ten times higher when all the volunteers came back to Yeshiva the next fall. Israel was on everyone’s mind; everyone wanted to go there.

Not to study—there were no Israel study programs then. But they sprouted fast. At first, the only place to go was The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Then the yeshiva programs started.

It was a crest, a wave.

For a few frantic weeks in 1967, I.T. and I rode the wave for all it was worth.

Reprinted with permission from the Intermountain Jewish News, May 13, 2005.

Finals Under Faraway Fire

By Toby Klein Greenwald

I can still remember the screaming headline in May 1967: “Straits of Tiran Closed.” I didn’t even know where exactly Tiran was, but I knew it was bad for Israel.

It was, in fact, a blockade that Egypt put on Israel’s access to the international waters of the Red Sea, and it was an act of war. A variety of Arab leaders had proclaimed, over the years, that they would “throw the Jews into the sea”—which sea was academic. On May 19, Nasser did throw the 3,500 United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) troops out of Sinai so that he could move the Egyptian army in.

When we heard the news, we were in the midst of preparing for and writing our twelfth grade finals in Yavne High School for Girls in Cleveland, Ohio. I had been active in Bnei Akiva for years, and already had a plane ticket (for July 10) to Israel, where I was to spend a year at Machon Gold, one of the few gap year study programs that existed at the time.

And then suddenly everything was thrown into question. What would happen in Israel? Today we speak about the miracles but in the dark days of May 1967, we only knew that the situation was perilous. Every day we said extra Tehillim during Shacharit, and when our class attended a Bais Yaakov convention in Montreal that year, I remember one of the Yavne Seminary students, who accompanied us, speaking with me about attending the seminary if going to Israel would not be an option. I could not fathom the possibility, but was suddenly thrown back into the dilemma of attending university in Cleveland, or seminary, or . . . what? How could I not fulfill my dream of spending my first year after high school in Jerusalem?

Many of our high school teachers were married to the rabbis of Telz Yeshiva, which had been transplanted to Cleveland from Lithuania. Having lost most of their families in the Shoah, and escaped themselves via Shanghai, these women were terrified by the prospect of war. We were close enough to the Holocaust to know that another one was a real possibility, especially against the backdrop of the violent Arab screams for death to the Jews. In and around school, the atmosphere was highly charged.

There are two especially vivid images that live in my memory from those days. One is of an Israeli girl in our school, wandering the halls in tears and saying that she had heard that Tel Aviv and Haifa—both cities in which she had relatives—had been devastated by incessant bombing. These were the only messages getting through—disinformation from the Arab radio stations. Israel kept a tight clampdown on any information.

The other image is one of unity. The Cleveland Jewish community decided to hold a mass prayer rally, and the largest available area was the parking lot of Conservative Park Synagogue. So the staff and students of our strictly Orthodox school loaded up on buses and joined the rest of the Jewish community—Orthodox, Conservative, Reform and unaffiliated—to pray together for peace in Israel.

And then the news came. “The Temple Mount is in our hands!” The Golan, the Sinai, Judea and Samaria, with our most sacred places—the Tomb of the Patriarchs, the Tombs of Rachel and of Joseph. There was a tremendous sense of joy and relief.

But nothing prepared me for the euphoria I sensed from everyone around me when I alighted from that small El Al plane (the larger ones were still in army service) on the tarmac of Lod (today Ben-Gurion) Airport on July 11, 1967. And the first words on the lips of every person we met were, “Welcome home.”

That first week in Israel I walked around the neighborhoods of Jerusalem, got to know the alleyways, and visited Hebron, where one could still see white cloths flapping in the wind, a sign of surrender, as the Arabs had been expecting the Israeli army to come in and massacre them, as they had done to the Jews in 1929.

And I visited the Kotel. Three Australian students at the Machon took me there on my first Shabbat. There were still huge boulders all over the streets—remnants of the concrete walls that had divided the neighborhoods of Jerusalem that had been torn down by the Israeli army a few weeks earlier. When we finally reached the Kotel, on that hot July afternoon, I began to cry on the shoulder of Shifra, one of Australians. “Don’t cry on me,” she said, “that’s what the Kotel is for. Cry over there.”

Toby Klein Greenwald is a frequent contributor to Jewish Action.

The Day Yerushalayim Was United

By Rabbi Joseph Karasick

My Dear Ones,

I’m exhausted, but I must write down my impressions while they are still fresh in my heart and in my mind.

We left New York City at 10 pm and arrived here non-stop at 2:15 pm local time. At Lod Airport we took a car for Jerusalem—and here the story begins.

Instead of taking the regular road to Jerusalem, we went by way of Latrun, which used to be Jordan. Everywhere you go the contrast between Jordan and Israel hits you in the eye. In one week the Israelis have paved part of the road already—and when you reach the unpaved (formerly) Arab roads, they are primitive, rocky, dusty . . . . All along the road you meet trucks of soldiers—all singing, laughing, happy. The motorists you pass on the road are all inwonderful humor, and all are in a state of euphoria. The cab driver tells you of this miracle and that experience—and the entire populace keeps pinching itself to make sure it’s true. “Two weeks ago this was Arab, and now it’s ours,” he says . . . .

And finally we arrived on the outskirts of Jerusalem and the streets are packed. Today is the day! Today, Jerusalem is formally united into one city, the Old and the New, and not only are the streets full of Jews from all over Israel, but a remarkable sight hits you—the streets are full of Arabs by the thousands; on foot, on mule, and in cars with Jordan license plates. For the first time Jordanians are streaming into the New City, and on the faces of the adults you can see surprise and envy at what they see—and the children look around as if they are onanother planet . . . . What a stunning sight!

The eye is assaulted by movement and color and you don’t know where to look first.

Israeli Troops with an armored car in front of the Lion’s Gate in the Old City of Jerusalem. Photo: Ilan Bruner

I finally get to the hotel . . . and can’t wait to check in and unpack. I must get to the Kotel for Minchah. I rush to a cab about 6 pm but the streets are packed, as the Arabs have a 7 pm curfew and they are all rushing back to the Old City. He finally gets me to the Mandelbaum Gate, but the guard tells us it is closed.

Finally, he says I must walk and I walk to the Jaffa Gate, which is the beginning of the Old City’s bazaar and marketplace, and I am transplanted back into history. The streets are narrow, dark, smelly, and dirty. . . . And in the midst of the Arab crowds walk thousands of Jews—young, old; men, women, children; with yarmulkes and without; boys, girls; soldiers and yeshivah-leit with peyoth, bekishes and knickers. The Jews are all proud and fearless. We walk through the winding streets—streets where a Jew hasn’t stepped for years, and where a Jew hasn’t stepped without fear for 2,000 years.

We walk up and down the winding, narrow streets and suddenly we come to an open space full of rocks and boulders. The Israel Army had knocked down entire blocks to make room at various points. My shoes are all white from the special Jerusalem dust. My suit is powdered with dust—but who cares. The road becomes more and more difficult to walk, and finally I meet a “Meah-Shearim” Jew and ask him if he’s going to the Kotel. He answers, yes. I ask him if I can go along with him, and he agrees. Finally, we reach the place, and before my eyes stands the Wall! In front of it all the houses have been knocked down and it’s difficult to walk. A whole platoon of soldiers are there. Israeli flags are flying from many heights.

I rush up to the Wall and kiss the stones. They are smooth from countless kisses and touches. They are cool, like cool, comforting, living flesh. And I begin to daven and I talk to the stones, and I know they listen. I place the kvitlach that I have in the cracks . . . . I remain there for about three-quarters of an hour to daven Ma’ariv also. I kiss the Wall goodbye, and I realize that it is dark. How am I going to make it back to the hotel in the dark, on foot, through strange roads, through Arab streets and quarters? I meet two Meah-Shearim yeshivah-leit and I ask them the way out. They tell me that they’re going my way and I can walk with them. We are in a wonderful mood and they are so friendly. These young men would probably not even have said hello to me last month, and now we’re wonderful friends, and almost brothers. They talk about “our army,” “our soldiers,” and only last month they were isolated in Meah-Shearim. I just pray to G-d this spirit lasts . . . . Baruch shehechiyanu v’kiymanu v’higiyanu laz’man hazeh.

Personal letter, dated June 29, 1967. Reprinted from Jewish Life (September-October 1967): 12-13.