Whose Museum of the Bible Is It?

In November 2017, the newly constructed Museum of the Bible opened in Washington, DC. It is reportedly the most technologically advanced museum ever built in the United States, and it is the largest privately funded museum in the country. The majority of the financial backing for the museum, which is free to the public, comes from the Oklahoma-based Green family, founder of the Hobby Lobby chain of craft stores and champion of Christian causes. Despite its backers’ beliefs, the Museum of the Bible goes out of its way to make religious Jews comfortable. To take one of many examples, a visitor must strain his or her eyes in order to see the term “Old Testament” used anywhere in the museum. Instead, it is almost always the “Hebrew Bible” or even the “Jewish Bible”—a signal to Jews that their Torah has not been superseded by Christianity. All of that said, the Museum of the Bible is not a Jewish museum, nor should it be mistaken for one. Nevertheless, Jewish visitors who remain aware of the limitations inherent in such an enterprise have much to gain from the Museum of the Bible. Indeed, somewhat paradoxically, a visit to the museum provides an opportunity even for literate Jews to learn something about the impact of our central sacred texts on the wider world and can have a profound impact on our sense of Jewish pride and religious mission.

Early reports of the museum’s founding were shrouded in controversy, mostly regarding the provenance of certain ancient artifacts acquired in war-torn Iraq. Skepticism also surrounded the Christian orientation of the founders of a large museum steps from the National Mall. The Green family is perhaps most famous for their successful Supreme Court case defending the right to exclude contraception from employee health plans. For potential Jewish visitors, these concerns are only heightened by the obvious question: a museum of whose Bible? Over the past two millennia, Jewish approaches to Tanach, read in the original Hebrew and through the lens of our traditional commentaries, have necessarily diverged widely from Christian readings of those same texts, which tend to be in translation and through the lens of Christological interpretations. For us, these problems raised by Christian perspectives on Tanach are themselves extremely grave as a stand-alone matter, even before accounting for the addition of the texts that comprise the New Testament. Were the Museum of the Bible devoted to the archaeology and history of the Bible in a primarily secular fashion, this too might raise certain challenges to the emunah (faith) of an Orthodox Jewish visitor. Yet, even such a museum would likely not be as off-putting as one that explicitly reads our sacred texts in a way that points toward radically different, and wholly unacceptable, religious conclusions. Fortunately for the Jewish visitor, the new Museum of the Bible does neither. Instead, it presents an eclectic wide-ranging celebration of the Bible, and most pronouncedly of the Bible’s roots in Judaism and the Land of Israel.

The third floor of the museum is dedicated to stories in Tanach. Photo: Julian Thomas for Museum of the Bible

In fact, one of three major permanent exhibits, the History of the Bible, strongly evokes two Israeli museums: the Israel Museum and the Bible Lands Museum, both located in close proximity to one another in Jerusalem. In a similar fashion to the aforementioned museums, the Museum of the Bible seeks to present information about the world of the Bible in a focused manner that primarily elucidates the mainstream Biblical account. Here we do not encounter “evidence” designed to contest the historical veracity of events such as Yetziat Mitzrayim, although that specific controversy is mentioned. Rather, we are presented with generally affirming artifacts, such as an ancient inscription of the Birkat Kohanim (Priestly Blessing), or fragments from the Cairo Geniza, in which Biblical and Jewish history come to life before our eyes. Some of this archaeological evidence may seem somewhat extraneous from a traditional perspective, but in the Museum of the Bible there is an additional goal that is advanced by its engagement with surrounding cultures of the Bible. By emphasizing the Levantine origins of the Bible, the museum also self-consciously reinforces the centrality of the Land of Israel and the Jewish people to any appreciation of what the Bible is about. Throughout the history exhibit, emphasis is placed on Biblical Hebrew; beautiful authentic Ashkenazi and Sephardi style recordings of Tehillim are piped into the room, and the “Translations of the Bible” section is clearly differentiated and distinguished from sections about the original Hebrew Bible. In the video presentation that explores the influence of the Bible on the Catholic Church, there is a surprising, even unnecessary, digression into how the rabbinic commentators were reading the Bible at the very same time that the Church was adopting its teachings. While a Jewish visitor might rightly choose to skip these excursions into Church history, there are frequent reminders that Jews are simultaneously reading this very same scripture in a way that is different and, the museum seems to suggest, more true to the original.

A visit to the museum provides an opportunity for Jews to learn about the impact of our central sacred texts on the wider world and can have an impact on our sense of Jewish pride and religious mission.

There are two capstones to the History of the Bible exhibit which hold interest for Jewish and non-Jewish visitors alike. One is the presentation of two beautiful intact Torah scrolls: a Sephardic Torah from the thirteenth century fused together with a nineteenth-century European Torah, and a medieval Ashkenazi Torah, also from the thirteenth century. It must be said that, for anyone accustomed to a living Torah that is regularly used in a synagogue, the sight of a Torah scroll locked behind a glass wall is always a wistful experience. However, watching the gaping eyes of Christian visitors marveling over these Torah scrolls redeems the situation in some way.

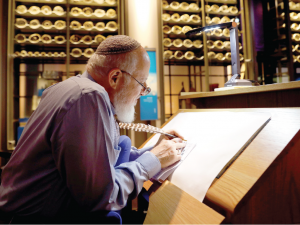

Rabbi Adam’s official role at the museum is as a scribe, but in practice he is the history exhibit’s “resident Jew.” Photo: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

The real highlight of the History of the Bible section comes close to its exit, where each day from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm an actual Orthodox Jewish sofer sits writing a Sefer Torah. The sofer is Rabbi Eliezer Adam, a genial American who made aliyah to Israel over forty years ago and left his home in Beit Shemesh to take up this position at the museum for the year. The museum’s founders were insistent on including a resident sofer in the museum in order to emphasize that the Jewish Bible is not something that sits behind glass walls, but is indeed a living text. Rabbi Adam’s official role at the museum is as a scribe, but in practice he is the history exhibit’s “resident Jew.” He answers visitors’ questions that span the gamut, from scribal arts to contemporary Judaism to Israeli politics and everything in between. I asked Rabbi Adam about his comfort level sitting in a Christian museum writing a Sefer Torah, halachically and otherwise. He replied with a big warm smile and said, “I believe we are living in atchalta d’geulah [the beginning of the redemption].” He explained that his experience in the museum has demonstrated to him that many gentiles have begun to recognize the Jews as the source of their “shefa” (abundance) and their “berachah.”

“We taught them about the one God,” he added, “and they are beginning to understand.”

The Museum’s “Stories of the Bible: The Hebrew Bible” immersive walk-through experience includes this “Exodus from Egypt” gallery, one of fifteen such theatrical environments. Here, dramatic stretched-cable walls with water lighting effects envelop guests as they pass through the sea. Photo: Alan Karchmer

With the exception of a loquacious living Jew from Beit Shemesh, the History of the Bible level of the museum is by and large a conventional museum exhibit. It is the technologically astounding “Stories of the Bible” level that situates the museum well into the twenty-first century. Of the three exhibits on this floor, the only one a Jewish visitor should pay attention to is the one devoted to the Hebrew Bible, a thirty-minute walk-through experience that seeks to give visitors an immersive taste—through lights, smoke, sound and engaging video animation—of the scope of the Hebrew Bible. Of course, no thirty-minute experience can approach even the tip of the iceberg of the literary and spiritual richness of Tanach. The experience is nevertheless aesthetically stunning, and includes fantastic modern interpretations of key moments in Tanach, all narrated in a way that is sensitive to and consistent with traditional Jewish interpretation. For example, in the video room which tells the stories of the Avot, all the figures are depicted as silhouettes and not with distinct faces or voices. The end of the exhibit depicts the Torah being read by a king of Israel in front of the fully built Beit HaMikdash. It goes without saying that something like Disney World for Tanach readers cannot substitute for learning Torah, but it is quite the experience nonetheless, and will only have greater significance for those already intimately familiar with the Bible.

Stories of the Bible – The Hebrew Bible Experience from BRC Imagination Arts on Vimeo.

Beyond the major exhibits which anchor the museum there are several supplementary exhibits, some of which will hold special interest for Jewish visitors as well. On the top floor there is an exhibit hall exclusively devoted to artifacts on loan from the Israel Antiquities Authority. At the entrance to the museum there is a video with sweeping vistas of modern Israel and its historic sites that rivals anything produced by Israel’s Ministry of Tourism and could easily be utilized to the same effect. There is an elaborate children’s play area, featuring stories from the Bible, such as those of Queen Esther and Shimshon, brought to life in engaging games and activities. There is a mix of Hebrew Bible and New Testament stories here, so parents should be on guard, but it tilts heavily toward the Hebrew Bible. There is a “guess the Biblical hero” game in which six out of eight characters are from Tanach. Here, when the last character was revealed, I overheard a non-Jewish visitor mutter “finally we get to see some Jesus.” This offhand comment may reveal more about the priorities and non-priorities of the museum than any review could.

The museum’s founders were intent on including a resident sofer in the museum so as to emphasize that the Jewish Bible is not something that sits behind glass walls, but is indeed a living text.

Putting aside religious issues, one could critique the museum for being largely about the Bible, without spending nearly as much time analyzing and engaging with the complexities of the text itself. Yet, from a Jewish point of view, this may actually be preferable. Indeed, visiting the Museum of the Bible is far from a proxy for Torah study, and attempts to fuse a visit with substantive religious meaning invite theological danger. Instead, a mature Jewish visitor can view the museum as a place to celebrate the influence our Tanach has had on Western civilization and even the farthest reaches of the world. Conversely, it is also a place for non-Jews who appreciate the Bible to learn how interwoven it is with the hearts, minds and homeland of the Jewish people. Rather than a site for religious learning, for us it is a place to feel a sense of pride in the far-reaching impact of Judaism across time and space.

Sarah Rindner teaches English literature at Lander College for Women in New York. Her writings on Jewish and literary topics have appeared in the Jewish Review of Books, Mosaic Magazine and other publications. She lives in Teaneck, New Jersey with her family.