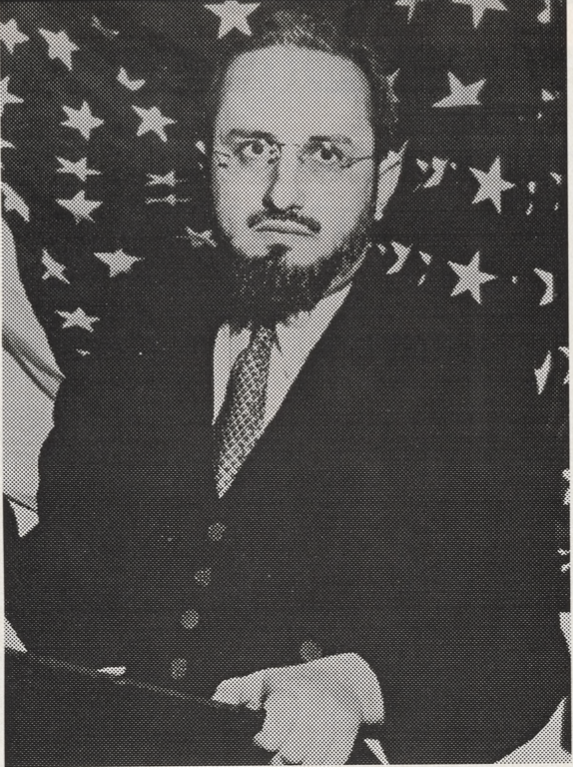

Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik: Biographical Highlights

Our rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, was born in Pruzhin, Poland on 12 Adar 5663 (1903). His father, Rabbi Moshe Soloveitchik, was the scion of a preeminent Lithuanian rabbinical family and the son of Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, widely known as “Reb Chaim Brisker,” as he served as the rabbi of Brisk (Brest-Litovsk). His mother was Pesia Feinstein, the daughter of Rabbi Elijah Feinstein, the spiritual leader of Pruzhan and author of Halichot Eliyahu. (He was the uncle of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein.)

Most of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s early years were spent in the White Russian town of Chaslovitz where his father served as rabbi. Here, at the local cheder, the seven-year-old youngster came under the influence of a teacher who was a devotee of Chabad. That year, the young Soloveitchik learned more about the Tanya, the focal classic of Chabad Chassidic literature, than about the Talmud. While his family protested these circumstances, the influence of the study of Tanya was to remain with Rabbi Soloveitchik for decades to come. It introduced him to the disciplines of Chassidic thought, philosophy and theology. For the next twelve years, the young Soloveitchik dedicated himself almost exclusively to the study of the Talmud and cognate literature.

His father became his sole teacher, and under Reb Moshe’s tutelage he mastered his grandfather’s “Brisker” method of Talmudic study. This unique approach was characterized by its insistence on incisive analysis, exact classification, critical independence and emphasis on Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah. He studied a goodly portion of Shas with his father, with special emphasis on the sections of Zeraim, Kodoshim and Taharot.

In his late teens, the young Joseph Baer broadened his vistas and attained the equivalent of a gymnasium education from private tutors. He entered the University of Berlin in 1925. Here, he majored in philosophy and was attracted to the neo-Kantian school. He received his doctorate in 1931 after completing his dissertation on Hermann Cohen’s epistemology and metaphysics. The latter was a German Jewish philosopher (1842-1918) who brought about a new interpretation of Kant’s philosophy which came to be known as the “Marburg School of neo-Kantianism.” Cohen stressed the supremacy of the mathematical and scientific—especially the physical—interpretation of reality. Joseph Baer retained an interest in mathematics and physics and utilized this approach in many of his philosophical lectures and writings.

In Berlin, he developed a close relationship with Rabbi Chaim Heller (1878–1960). The latter was a unique Torah scholar who combined a vast erudition in Talmudic literature with a thorough competence in modem methods of textual research. Rabbi Heller established an advanced yeshivah, the Bet ha-Medrash ha-Elyon, in Berlin for the intensive study of classic rabbinical literature combined with the modern scientific approach towards research in Bible and Talmud. Although he did not attend Rabbi Heller’s yeshivah, the young man be came a devotee of Rabbi Heller and their relationship developed into a paternal bond.

While his family protested these circumstances, the influence of the study of Tanya was to remain with Rabbi Soloveitchik for decades to come.

Rabbi Soloveitchik married Tonya Lewit in 1931. She was the recipient of a Ph.D. in education from Jena University and was to ably assist her husband in all his endeavors until her death in 1967. In 1932 they emigrated to the United States where his father, Reb Moshe Soloveitchik, had been heading the Talmudic faculty of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (popularly known as the “Yeshiva”) in Manhattan since 1929. A few months after his arrival, the younger Soloveitchik became rabbi of the Orthodox Jewish community of Boston, Massachusetts. This city was to remain his home throughout the rest of his life.

These years were filled with the vexations and burdensome quests of the American Orthodox rabbinate of that period. Rabbi Soloveitchik’s main achievements in Boston were in the area of Torah education. In 1937, he founded the first Jewish day school in New England, the Maimonides School, which later expanded into full elementary and high school programs. Rabbi Soloveitchik and his wife were to retain an active interest in the school’s administration throughout the ensuing decades. He also organized an advanced yeshivah called Heichal Rabeinu Haym Halevi and Yeshivath Torath Israel in 1939 to accommodate the influx of erudite European yeshivah students who were then reaching American shores. Rabbi Soloveitchik delivered advanced Talmudic lectures to these select students and the new school continued to function until he succeeded his late father at the New York Yeshiva in 1941.

In 1935, Rabbi Soloveitchik journeyed to Palestine (this was to be his only visit to the Holy Land), where he was a candidate for the position of Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv. He was not successful in this attempt. Years later, following the death of Chief Rabbi Isaac Herzog in 1959, Rabbi Soloveitchik declined to be a candidate to succeed him as Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi of Israel.

Rabbi Soloveitchik explained why he did not take this position:

One of the reasons why I did not accept the post of Chief Rabbi of Israel . . . was that I was afraid to be an officer of the state. A rabbinate linked up with a state cannot be completely free. I admire the rabbis in Israel for their courage in standing up to the problems there and displaying an almost superhuman heroism. However, the mere fact that from time to time halakhic problems are discussed as political issues at cabinet meetings is an infringement on the sovereignty of the rabbinate. (1964 interview in The Boston Jewish Advocate, cited in a Yeshiva University news release.)

It may also be that, by this period, Rabbi Soloveitchik was at home in the United States and totally fulfilled as the rebbe, teacher and leader of Westernized Torah Jewry. Rabbi Soloveitchik became the senior Rosh HaYeshivah at the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, which later evolved into the focal component of Yeshiva University (1945). On May 13, 1941, he delivered his inaugural lecture in this capacity on the topic: “A buyer acquires the right to the debt as soon as the bond is delivered to him” (Baba Batra 75b-76a). Rabbi Soloveitchik was to continue his lectures at Yeshiva until illness forced him to retire in 1985.

This position did the most to project him into prominence upon the Jewish scene. He became the spiritual mentor of the majority of the American trained Orthodox pulpit rabbis. Many were ordained by him in his capacity as a member of the Yeshiva’s ordination board. In addition to his lectures in the Yeshiva proper, Rabbi Soloveitchik also served as Professor of Jewish Philosophy in the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Yeshiva University. Although his activities at the New York Yeshiva became more and more time-consuming, Rabbi Soloveitchik continued to reside in Boston and weekly commuted to New York.

These achievements at Yeshiva University became the central facet of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s spiritual personality. Time and again, he would stress that his calling in life was to be a “melamed.” He succeeded in raising two generations of students who related to him as their rebbe muvhak. Despite the changes in the sociological, educational, and economic backgrounds of the Yeshiva’s student body during this period (1941–1985), Rabbi Soloveitchik became their mentor and was able to relate to them in the context of their back grounds. In 1960, he switched from Yiddish to English as the language of instruction in his class room. He made the adjustment with a flourish. With a Yiddish accent accompanying his soft-spoken, high pitched tone, he utilized the English language to paint portraits of Torah, Talmud, philosophy, theology, mathematics, physics and Western scholarship with academic and flowery prose.

Rabbi Soloveitchik was initially active in the Agudat Harabanim (the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada). Founded in 1902, this organization united the East European-trained rabbis who ministered to the American Jewish immigrant communities. Gradually, Rabbi Soloveitchik became more active in the Rabbinical Council of America. The latter organization evolved from the Yeshiva’s Rabbinical Alumni Organization and the Rabbinical Council of the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America. In 1935, these bodies merged and most American-trained rabbis joined the newly formed Rabbinical Council of America.

In 1953, Rabbi Soloveitchik was formally appointed the chairman of the Halakhah Commission of the Rabbinical Council. In this capacity, he was to wield decisive influence on the public stance of the Council. Among his memorable decisions were his unequivocal opposition to mixed seating in synagogues. He went so far as to prohibit listening to the shofar, if blown in a deviant house of worship. Rabbi Soloveitchik advised the person to pray at home and not to hear the shofar, rather than worship in such a synagogue. He also opposed many aspects of the dialogue initiated by the Catholic Church with Jewish leaders as part of the Church’s ecumenical movement during the 1960’s. He held that there could be no dialogue concerning the uniqueness of each religious community, as each is an individual entity which cannot be merged or equated with the other, since each is committed to a different faith.

Despite the changes in the sociological, educational, and economic backgrounds of the Yeshiva’s student body during this period (1941–1985), Rabbi Soloveitchik became their mentor and was able to relate to them in the context of their back grounds.

Rabbi Soloveitchik did not fully agree with the public ruling issued in 1956 by eleven leading American Roshei Yeshivah which prohibited the membership of rabbis and synagogues in groups which also included non-Orthodox clergymen and synagogues. Rabbi Soloveitchik clarified his position that on matters of halakhah, he too agreed that no cooperation was possible. However, when the issues are klapei chutz (vis-a-vis the non-Jewish world) and Jewish interests are at stake, division in the Jewish camp can endanger the entire community.

Rabbi Soloveitchik’s association with the Rabbinical Council became pivotal in the organization’s growth. His presence and guidance provided succor and aid for its rabbis who were caught up in the difficulties of representing and perpetuating Torah on the American scene. In 1958–59, Rabbi Soloveitchik delivered a series of lectures on Jewish social philosophy to a group of social workers in New York. He also was the principle Jewish representative in Yeshiva University’s Institute of Mental Health Project which was undertaken in 1960 (in conjunction with Harvard and Loyola Universities) to study religious attitudes toward psychological problems. The lectures delivered to these groups later served as the basis for a portion of his published philosophical writings. Rabbi Soloveitchik represented the entire American Jew ish community as a member of the Advisory Committee on Humane Methods of Slaughter, set up by the United States Secretary of Agriculture (1958).

Although originally among the founding members of Agudat Israel in the United States in 1939, he later became a stalwart member of the Mizrachi movement. From 1946 until his death, Rabbi Soloveitchik served as the Honorary President of the Religious Zionists of America (formerly Mizrachi). On Israel Independence Day in 1956, he delivered the main address at a public convocation at Yeshiva University. Later published under the title Kol Dodi Dofek: It is the Voice of My Beloved That Knocketh, this essay gained renown as a seminal statement of religious Zionism in the post-Holocaust era. Delivered in Yiddish, published in Hebrew, this essay was later translated into English and Russian. Rabbi Soloveitchik sympathized with the ideals of the Bnei Akiva organization in North America. Hundreds of his students and their families made aliyah, finding encouragement and support in his Religious Zionist theological teachings.

Gradually, Rabbi Soloveitchik took his place as the unchallenged leader of the popularly named “Modem Orthodox” movement in North America. Rabbi Soloveitchik was never totally at home in the milieu of American modem Orthodoxy, feeling that it lacked deep emotional foundations and self-effacing commitment. (See his eulogy on R. Chaim Heller, Pleitas Sofreihem, page 148.) Nevertheless, it was here that his leadership was widely accepted. Among his followers, he was known simply as “The Rav.” His main influence on the masses was through his students and the rabbis who followed his teachings. In addition, his public lectures and discourses enabled wider audiences to be in closer contact with the master. As a talmudic and halakhic expositor, the Rav had an unusual facility for explaining difficult technical problems. He was also an orator of note in his native Yiddish, as well as in English and Hebrew. The annual halakhic and aggadic discourse which Rabbi Soloveitchik delivered in Yeshiva University on the anniversary of his father’s death attracted thousands of listeners. These Yahrzeit Drashot would often last from four to five hours. They were regarded as the major yearly academic event for American Orthodoxy.

In addition, there were his annual “Teshuvah” lectures, which were delivered under the aegis of the Rabbinical Council of America and the Tonya Soloveitchik Memorial Lectures at Yeshiva University. These discourses have been described as an American version of the classical rabbinic legal lesson delivered by the master of an Academy during the talmudic period.

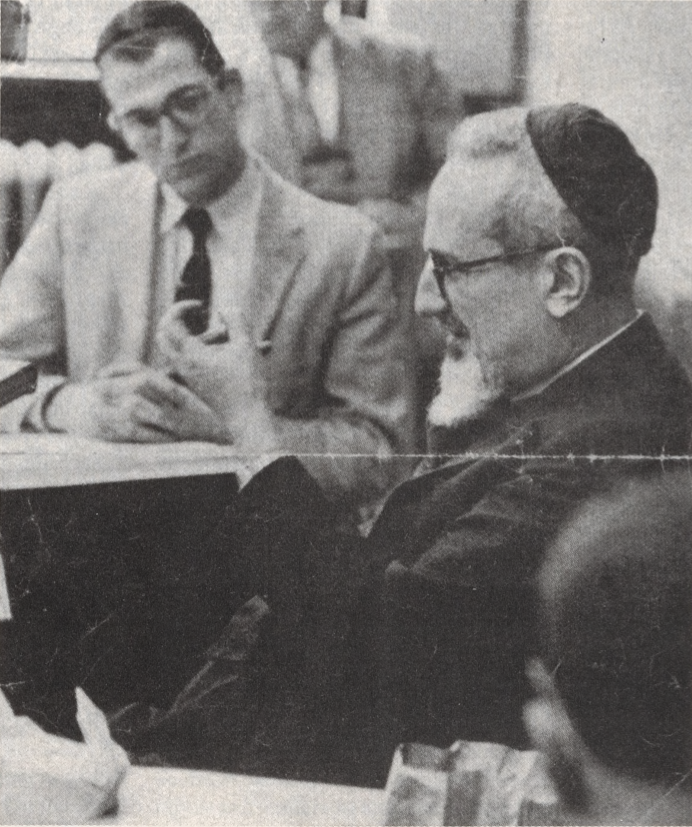

The Rav also served as the spiritual leader of Congregation Morya on the Upper West Side of Manhattan from 1950 to 1960. Here, his main responsibility was to deliver a weekly Talmudic lecture. For decades (even when no longer the rabbi of the congregation), these lectures were attended by hundreds of rabbis and lay people from the greater New York area. Rabbi Soloveitchik was particularly prolific in the many and varied lectures he gave for the members of the Rabbinical Council and the Yeshiva University Rabbinic Alumni. The high point of every annual convention and midwinter conference was generally the lecture presented by the Rav. Their themes were varied and stressed either halakhic, philosophical, homilectical or aggadic insights. In August, Yarchei Kallah seminars were sponsored by the Rabbinical Council at the Maimonides School in Boston. Rabbi Soloveitchik would elucidate a central theme in four major lectures which were delivered during a three-day period before the assembled rabbis. In 1972, such a lecture was described by an article which appeared in The New York Times (June 23, 1972, p.39):

Among Orthodox Jews he is known simply as “the Rav”—the rabbi’s rabbi. He holds no elective office and occupies no pulpit, yet the breadth of his learning and the depth of his piety is such that his authority on matters of Jewish law is unchallenged. Some say that only a half a dozen scholars have shown such brilliance since Maimonides in the 13th century.

His name is Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, and this week his disciples had another chance to sit at his feet in search of learning and inspiration. As he does every year, the 69-year-old scholar addressed his fellow rabbis at the annual meeting of the Rabbinical Council of America, the largest of the country’s Orthodox rabbinical organizations.

He sat with his feet crossed in front of a table bearing an open volume of the Talmud, a few bulky reference works and a glass of milk. He spoke in a relaxed, rather informal manner, waving his right hand in the air occasionally to emphasize points and asking frequent questions of members of his audience, many of whom had tape recorders at their side.

“I’ll take it home and play it for colleagues who weren’t able to get here,” said Rabbi James Gordon of Oak Park, Mich. “We’ll go over and over it, maybe three or four times.”

Rabbi Soloveitchik’s prominence was not accidental. It was a result of considerable exposure to an educated public which sought his guidance. Prior to his arrival at Yeshiva and Yeshiva College which later became Yeshiva University, his intellectual life had been primarily “an epoch of concentration” characterized by intensive study and, in a sense, by isolation. Once he succeeded his father at the Yeshiva, his activities shifted their emphasis and he gradually became a focal figure in the limelight of American Orthodoxy.

Nevertheless, the Rav himself remained essentially a lonely figure, although he was surrounded by many loyal students and devoted associates. He described himself as a shy person and denied that he was an “authority” in the usual sense of the word. “I have many disciples, but I never impose my views on anyone. Judaism is a society of free and independent men and women bound by a single commitment and vision.” (Ibid, p.74)

Due to his family’s tradition of perfectionism, Rabbi Soloveitchik was reluctant to publish during his lifetime. His grandfather, Reb Chaim Brisker, published only a single volume on Maimonides, which appeared posthumously some 17 years after his death. Since all of his major lectures were delivered and preserved in manuscripts, the Rav was asked why he published so little. He replied: “I am a funny animal. I am a perfectionist. I am never sure something is the best I can do.” (Ibid.) For decades, his main published work was a weighty essay, Ish haHalakhah, which appeared in the first volume of the scholarly Hebrew quarterly Talpioth (1944). This work was considered his magnum opus and was later translated into English by Lawrence Kaplan as Halakhic Man (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1983).

The Rav himself remained essentially a lonely figure, although he was surrounded by many loyal students and devoted associates.

During the last decade or so of his active endeavors, Rabbi Soloveitchik softened his resistance to publishing his work. Subsequently, many volumes appeared under his name, including those he published and others that were edited from his manuscripts or public discourses. Among them were a selection of his Teshuvah lectures, edited by Pinchas Peli, entitled Al haTeshuvah, discourses in memory of his father published from manuscript by Machon Yerushalayim under the title Shiurim leZekher Abba Mori; and a number of volumes edited from both manuscripts and recordings by Moshe Krone of the Torah and Culture Department of the World Zionist Organization. Rabbi Abraham Besdin issued two volumes of reconstructions of focal themes in the Rav’s public lectures, Reflections of the Rav, and Rabbi Harold Reichman of the Yeshiva University Talmud faculty edited his discourses on various Talmudic tractates.

Rabbi Soloveitchik published a major essay Entitled “The Lonely Man of Faith,” dedicated to his wife Tonya, in the Summer 1965 issue of Tradition. An entire issue of Tradition was later devoted to the Rav’s articles and lectures (Spring 1978). Five of his addresses at conventions of the Religious Zionists of America during the period 1962–1967 were published in both Hebrew and English by Rabbi David Telsner of the Tal Orot Institute in Jerusalem.

The final years of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s life were spent at his daughter’s home in Brookline, Massachusetts, as ill health excluded his continued participation in public undertakings. Death came on Chol haMoed Pesach, 18 Nissan 5753 (April 8, 1993). Although it was in the middle of the Passover festival, the news of his passing spread quickly throughout the Jewish world. He was deeply mourned by his devotees and students in Israel, the United States and worldwide.

Rabbi Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff is Professor Responsa Literature and Jewish History at the Gruss Kollel of Yeshiva University and Midreshet Moriah for Women in Jerusalem. He is the author of Bernard Revel: Builder of American Jewish Orthodoxy; The Silver Era: Rabbi Eliezer Silver and His Generation and Rakafot Aharon.

Rabbi Joseph Epstein, a talmid of Rabbis Soloveitchik and Rakeffet, is the editor of Shiurei Harav: A Conspectus of the Public Lectures of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, published by Hamevaser in 1974.