Rabbi Dr. Isaiah Wohlgemuth: A Beloved Teacher of Tefillah

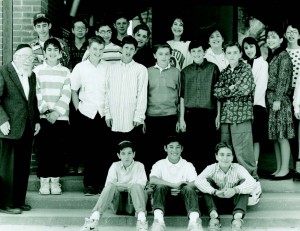

Rabbi Isaiah Wohlgemuth, a master teacher of tefillah, seen here with his Shabbat Talmud class; some of the kids walked two miles each way on Shabbat to learn with him. Photo taken in 1992. Photo courtesy of Maimonides School

In the American Modern Orthodox community, the widely acknowledged master of teaching tefillah was a Holocaust refugee from Germany who made a new home in Boston. Rabbi Isaiah Wohlgemuth, who had semichah from Berlin’s Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary and a doctorate in education from Boston’s now-defunct Calvin Coolidge College, is remembered by generations of students from Maimonides School, the Boston institution where he taught from 1945 to 1997. His synagogue in Kitzingen was destroyed on Kristallnacht; he spent time in Dachau, was liberated and came to the United States shortly thereafter.

The men and women who studied with Rabbi Wohlgemuth recall his trimmed beard and lilting German accent, his concern for students whom he treated as his own grandchildren and, above all, his signature class on the foundations of prayer.

“His . . . course was known to students as ‘BH,’ for Biur HaTefillah, a guide to Jewish prayer,” the Boston Globe reported in the obituary for Rabbi Wohlgemuth when he died in 2008 at the age of ninety-two.

“In blogs,” the Globe reported, “former students recalled that he brought ‘kavanah,’ the Hebrew word for intention or focus and meaning, to thousands of students.”

Students say the weekly class continues to influence their tefillah, decades later. An outgrowth of Rabbi Wohlgemuth’s life and approach to life, “BH” brought a wide variety of sources to the study of, and appreciation for, prayer. “Its emphasis is on the rationale, meaning and various halakhot of tefillah . . . to emphasize the interpretation of the words and the structure of the siddur,” the rabbi wrote in the Ten Da’at journal, a journal of Jewish education, describing his course. “A bibliography . . . would include all of Jewish scholarship: halakha and aggada, Talmud and poskim, philosophy and history, Jewish literature and poetry. I also teach Rav [Joseph Ber] Soloveitchik’s ideas and philosophy. . . ”

In the front of Maimonides’ sanctuary, a pair of shtenders still stands, as a memorial, in the exact spots where Rabbi Wohlgemuth and the late Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik, the philosophical leader of the Modern Orthodox movement who founded the school in 1937, prayed daily.

A book by Rabbi Wohlgemuth, A Guide to Jewish Prayer, grew out of his course. “The fact that in recent years many books have been written and published on prayer shows that many contemporary Jews look to these prayers for guidance in difficult times,” the rabbi wrote in an epilogue.

Briefly discontinued after Rabbi Wohlgemuth’s death, his tefillah curriculum was quickly reinstituted under a new endowment at the school. Patterned after his teachings, it is offered to students weekly in the ninth, tenth and eleventh grades, says Nathan Katz, head of school. “We’re following in his footsteps.”

As under Rabbi Wohlgemuth, the classes feature a blend of history, philosophy and halachah. A course outline for the first year of the class—“Jewish Thought I: Prayer”—includes an introduction to fundamental berachot, a selection of commentaries, a section of “ikkarei emunah” (fundamentals of faith) and a thorough look at the prayers that Jews recite every day.

“ . . . alumni say Rabbi Wohlgemuth’s class was the one in which they paid the most attention, the one whose notes they have saved over the years.”

Alumni of Maimonides tell different stories of the influence that Rabbi Wohlgemuth exerted—and continues to exert—on their lives. Mark Blechner, who graduated in 1967, still attends the school’s daily morning minyan because, he says, he feels at home in the atmosphere of sincere davening that is a carryover from the rabbi’s years there. Other alumni say Rabbi Wohlgemuth’s tefillah class was the one in which they paid the most attention, the one whose notes they have saved over the years. “When I pray today,” Blechner says, “I feel as if Rabbi Wohlgemuth is watching me.”

When Rabbi Wohlgemuth died, the Globe obituary quoted Steven Bayme, director of the Contemporary Jewish Life Department at the American Jewish Committee, as saying, “The world of Jewish text is a difficult one to open up—some people take to it naturally, some people struggle with it, but he made the text accessible to everyone.”

“By encouraging inquiry into these areas [of prayers’ origins], he imbued students with the capacity to consider what meaningful prayer actually constitutes, and to understand liturgical texts and procedures with the same tools we bring to the study of other subjects,” Bayme says. “That at least opens the door to meaningful tefillah experiences absent gimmickry or contrived expressions of piety.”

“I not only remember the halachic, philosophical and aggadic teachings he left us with, but I have used them over the past decades nearly every day,” Rabbi Asher Lopatin, president of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah and a 1982 graduate of Maimonides, wrote on a memorial web site for Rabbi Wohlgemuth. “Certainly in my own tefillah, I can’t get through Yishtabach without thinking of why it is in the reflexive; I can’t think of the first bracha of the Amidah without thinking of whether we really have the merits of our forefathers or not, or geshem vs. gashem, or a million other parts of the tefillah where understanding and kavanah were built on Rabbi Wohlgemuth’s teachings.”

Leah Lightman, who attended Maimonides in the 1970s, says she was shopping in a book store about twenty years ago in the Geula neighborhood of Jerusalem when she came upon a copy of Rabbi Wohlgemuth’s book.

“I became very emotional,” Lightman says. The store owner, noticing, came over. “You must be from Boston,” he said.

Many customers who see Rabbi Wohlgemuth’s photograph on the cover “get very emotional,” the store owner explained. “I find out they’re from Boston,” also former students of Rabbi Wohlgemuth.

Lightman, who now lives on Long Island, says Rabbi Wohlgemuth’s example of personal piety in the school minyan was as influential as his classroom teaching. He stood at his shtender, Lightman says, “as if there was nothing going on [in the world] beyond his conversation with the Almighty.”

Steve Lipman is a frequent contributor to Jewish Action.